Scientist of the Day - James Short

James Short, a Scottish telescope maker, was born June 21, 1710. Orphaned at a young age, he showed himself to be an exemplary student, and he was encouraged to attend the University of Edinburgh, which he did, and study for the cloth, which he did not. Instead, he attended the mathematical lectures of Colin Maclaurin, an Edinburgh professor who was an avid follower of Isaac Newton's work, especially his Opticks (1704). Maclaurin apparently had an interest in making telescopes – at least he had a room at his college that was devoted to that art - and when he learned that Short wanted to learn how to build astronomical instruments, he gave him free use of his workshop. Short repaid him by crafting the finest reflecting telscopes in the British Isles from 1732 to 1760.

We have written several times about the problems of building reflecting telescopes, or reflectors, most recently in our post on John Hadley, the most successful reflector-builder before Short. The main problem with building a useful reflector lay in shaping the main mirror (the primary), which must be a paraboloid. If you make the mirror of glass, which is relatively easy to grind and polish, you then have to add a reflecting surface, usually some kind of mercury film, and no one really solved the problems of making a mercury-backed glass mirror. The alternative was to make the mirror of a reflective material, some kind of shiny metal. The problem with a metal mirror is that it was much trickier to grind it into shape and then give a high polish. Newton found that his reflecting telescopes (he made two of them) tarnished very quickly, and others had a similar problem trying to come up with a recipe for "speculum," the name given to whatever alloy was used to make a mirror. It had to be reflective but slow to pit and corrode. Some combination of copper and tin was used, but the exact recipe was crucial and kept secret by artisans.

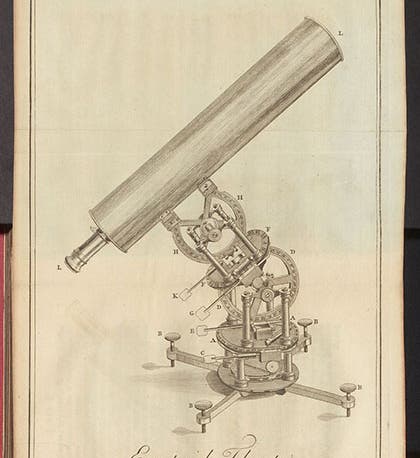

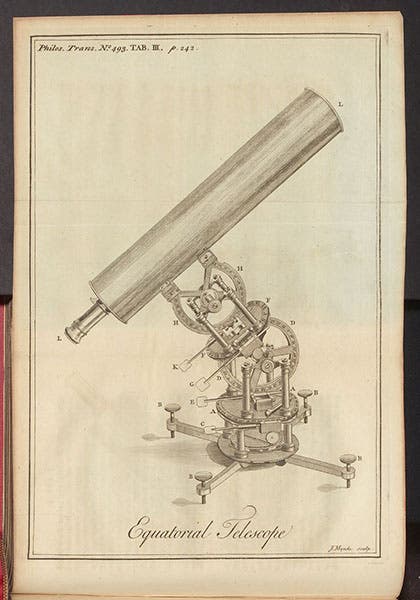

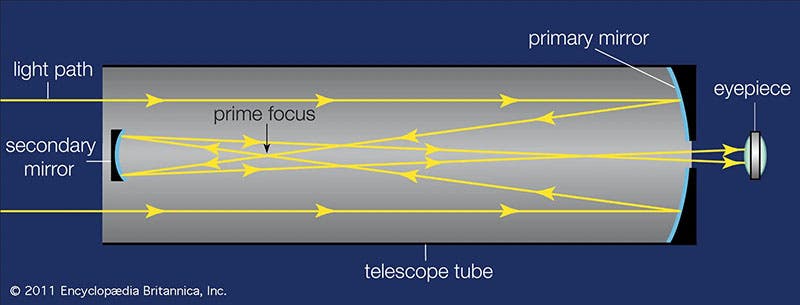

Short seems to have made some successful reflectors out of glass. but he soon turned to metal mirrors, found a suitable recipe for his speculum, and started churning out small reflectors (4-5 inch diameter, focal length of 6-12 inches) that performed better than anyone else's small refractors (third image). Most of his reflectors were Gregorians, invented by James Gregory, where there is a secondary concave mirror within the telescope that reflects the focused rays of light out through a small hole in the center of the primary to the eyepiece. This differed from Newton’s design. We have borrowed a diagram from the Encyclopedia Britannica, if you want to see howe as Gregorian works (fourth image). Maclaurin praised Short’s telescopes to his fellow astronomers, who came to Edinburgh to buy them. To increase his business, Short moved to London in 1736. He made over 1300 instruments in his 30 years in his Surrey Street shop, and became a very wealthy man.

Light path for a Gregorian telescope such as those built by James Short; light enters the tube from the left, is reflected off the concave primary mirror at the right, is reflected again by the small concave secondary mirror at the left, and passes out to the eyepiece through a small hole in the primary mirror, Encyclopedia Britannica, 2011 (cdn.britannica.com)

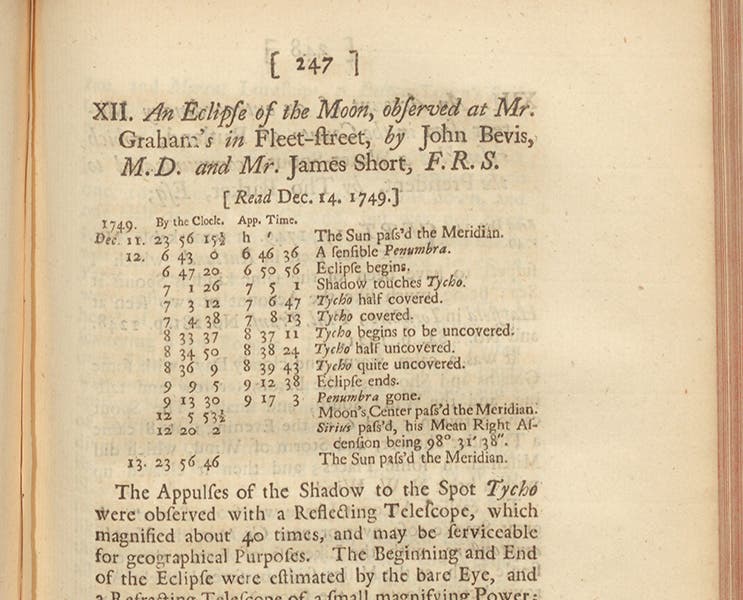

Short also earned the respect and friendship of professional astronomers, which was not always the case with artisans. He was elected to fellowship in the Royal Society of London when he was 27, just a year after he moved to London. He knew James Bradley, the Astronomer Royal, and John Bevis, of star atlas fame, and he befriended John Harrison, who was working on his marine chronometer and did not have many friends in scientific circles. Short was often invited to observing parties and asked to bring along a reflector. While reading an article in the Philosophical Transactions on his equatorial reflector (source of our first image), I noticed a short piece describing how he and John Bevis had gone to the home of instrument maker George Graham to view a lunar eclipse (fifth image). This happened often.

It has been conjectured that Short was able to make so many telescopes because he contracted out the mounts, such as the elaborate one in our first image. Most instrument makers built their own mounts, which require elaborate metal-working equipment such as lathes. But building a mount did not require that much specialized knowledge. Making mirrors, however, requires considerable skill, but not much in the way of equipment. By spending his time on polishing mirrors and by not having to equip an elaborate shop, Short was able to produce more and spend less. That, I guess, is how you make money building telescopes.

There is a fine portrait of Short, thought to be by Benjamin Wilson, in the Royal Observatory, Edinburgh (second image). We discussed this portrait in a post on Wilson not long ago.

Short was 58 when he died on June 14, 1768. He is buried in All Saints Churchyard in Edmonton, Greater London. There is no grave marker.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.