Scientist of the Day - James Murray

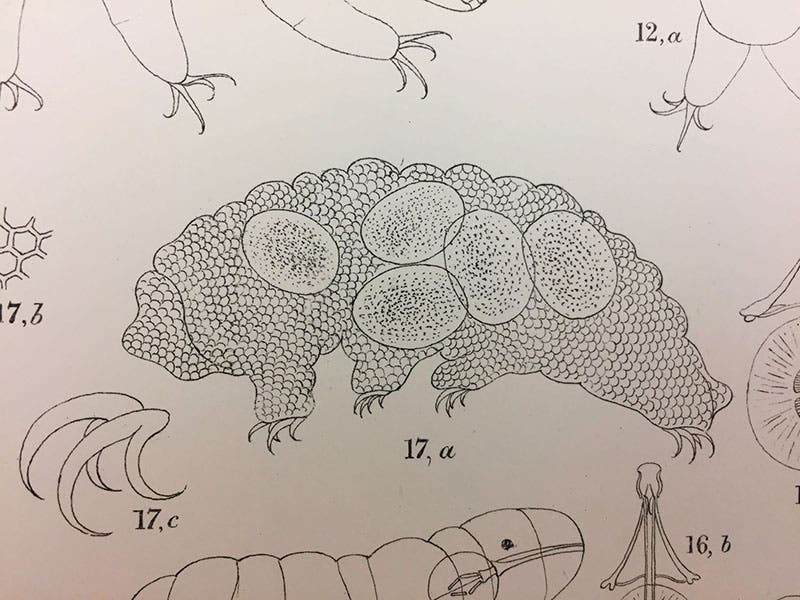

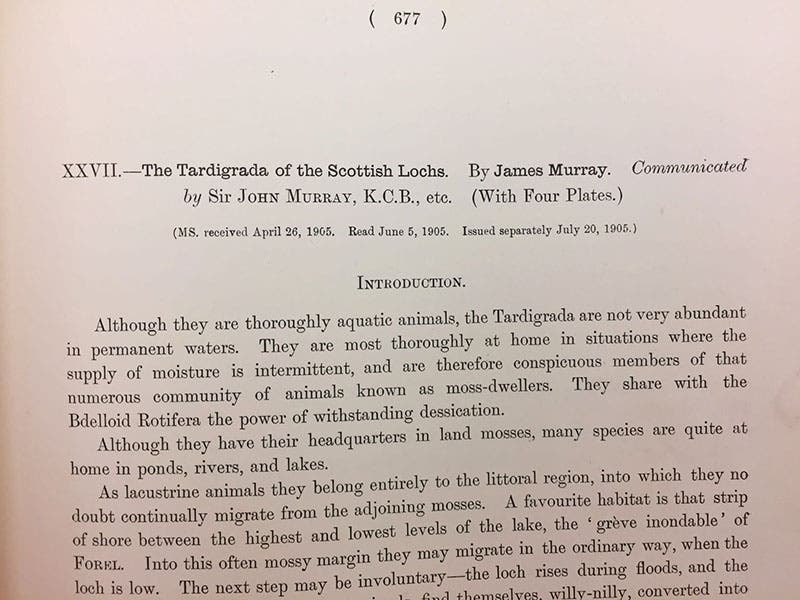

James Murray, a Scottish biologist and explorer, was born July 21, 1865, in Glasgow. Murray (not to be confused with the James Murray who was the editor of the first Oxford English Dictionary) became an expert on marine invertebrates, and in 1902, he accompanied yet another Murray, this one John Murray, a marine biologist, when he took depth measurements of all the Scottish lochs, while our Murray used the opportunity to study the organisms dwelling in the depths and along the shores. James Murray’s special interest was tardigrades, or water bears, which most people find entrancing, mostly because they lumber around their microscopic environment like, well, water bears. The verb "lumber" is surely not appropriate for a micro-beast about half the size of a grain of salt, but we use it anyway.

Murray published a number of papers on tardigrades from 1905 to 1913; we show here a detail of a tardigrade from a plate that he published in 1905 in the Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, and a detail of the first page of his article, if you are curious about his tardigrade prose. If you too are intrigued by these 8-legged waddlers, you will surely enjoy this short video showing tardigrades in action, from the PBS show Science Friday, made available in 2013.

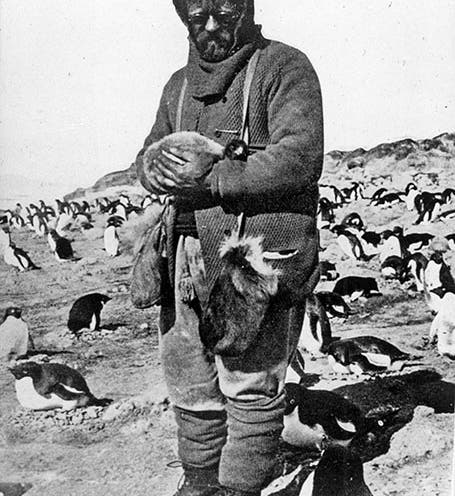

Murray then took part in the Nimrod expedition to Antarctica (1907-09), which was led by the not-quite-as-famous-as-he-soon-would-be Ernest Shackleton. A single report on Antarctic tardigrades emerged from this, which we have in our collections, as well as a single photo of Murray in Antarctica (first image). Perhaps photos of Murray in Antarctica are so scarce because he seems to have been the unofficial photographer, as all the photos of Shackleton and the rest of the crew are credited to Murray. Murray also wrote an account of the Nimrod Expedition, Antarctic Days (1913), which is not held by our Library.

The most notorious adventure undertaken by Murray came in 1911, when he agreed to accompany Percy Fawcett and several others on an expedition to explore a remote area in Peru and Bolivia. Murray was not used to conditions in the tropics, suffered greatly on the expedition, became practically incapacitated, and was no help to Fawcett and the rest. Eventually, they sent him away and went on without him. Murray survived, and when he got back to England, he planned to bring legal action against Fawcett for dismissing him, but he never followed through. If you have seen the film, The Lost City of Z (2016; fourth image, above), you will recall that Murray, played by Angus Macfadyen, was portrayed as an inept, overbearing, vengeful man, who tried to sabotage the expedition when Fawcett decided to get rid of him, and who berated Fawcett in front of the Royal Geographical Society after Fawcett's return. None of this really happened. Of the two men, Fawcett was far crazier and more egotistical than Murray, and even less competent, or so it is said by some historians.

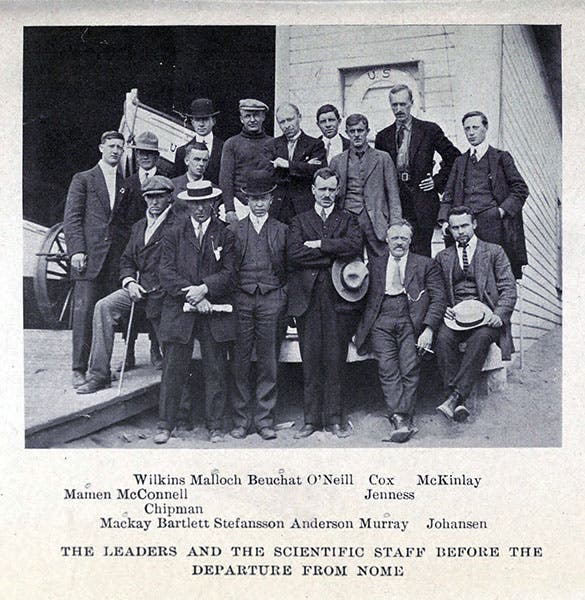

If Murray was the more stable of the two on the Fawcett expedition of 1911, this was not evident on his last adventure, when in 1913 he joined the crew of the Karluk for a Canadian expedition into the Chukchi Sea between Alaska and Siberia. In a photograph taken before departure (fifth image), Murray is the second from the right in the front row. The captain, Robert Bartlett, is second from the left, and the expedition leader, an anthropologist named Vilhjalmur Stefansson, is at center front wearing a bowler. The ship was frozen into the ice almost immediately and stayed frozen in through the fall and into the early winter, while the ship drifted westward toward Wrangel Island off the northern coast of Siberia. The ship was finally crushed by the ice in January of 1914, just as Shackleton’s Endurance would sink 22 months later, but with a far less glorious outcome. Murray and three others decided to set out on their own on foot in early February of 1914, which was not a good time to be out on the ice. All four disappeared into the cold and were never seen again. Fourteen of the crew of 25 survived and were eventually rescued. Below is a modern map of the ill-fated expedition; Murray disappeared near the end of the red track, where it says “sunk”.

It is a good thing we have those tardigrades to remember Murray by; otherwise, he might not be remembered at all, except for being cast as an arrogant antagonist in a not very accurate adventure film. The poor fellow doesn't even have a tombstone. If he did, it would have moss on it, and where there is moss, there are tardigrades. And since tardigrades are virtually indestructible, can survive in outer space and near absolute zero, and will endure complete desiccation for ages, they would provide Murray the kind of immortality he doesn't otherwise have.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.