Scientist of the Day - James Melville Gilliss

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

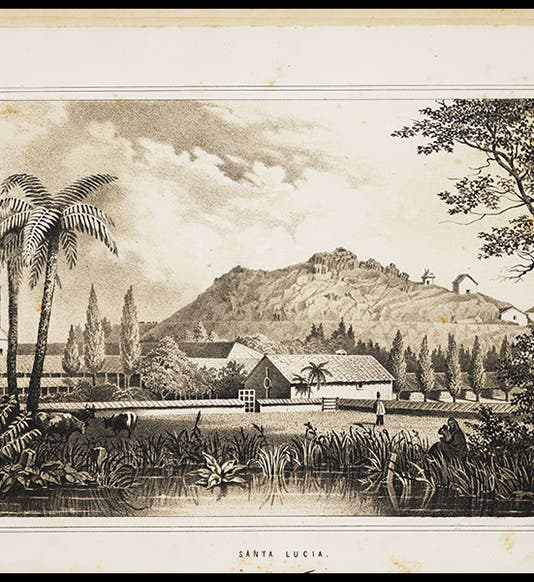

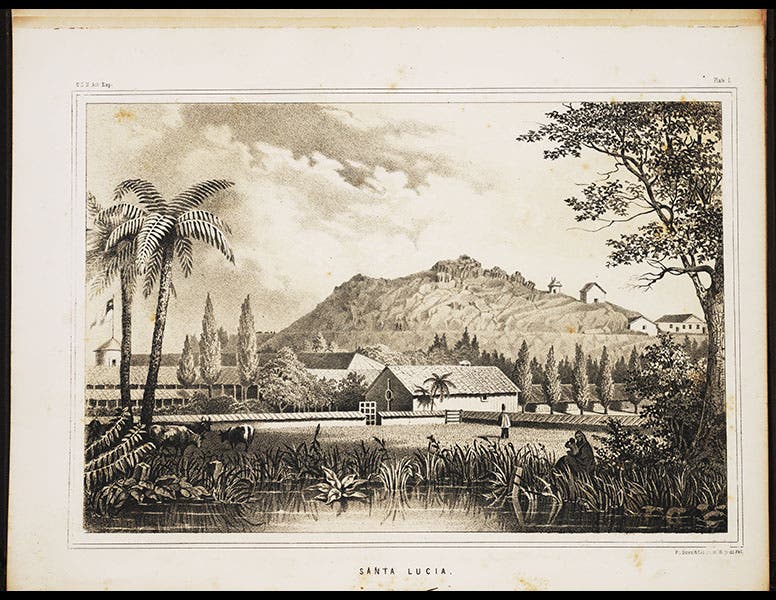

James Melville Gilliss, an American naval officer, and astronomer, was born Sep. 6, 1811. Beginning his career as an astronomer for the Depot of Charts and Instruments in Washington, he moved on to head the Depot and was largely responsible for founding the U.S. Naval Observatory in Washington in 1844. In 1848, Gilliss was chosen to lead the U. S. Naval Astronomical Expedition to South America. His mission was to make observations to help determine a more accurate figure for the solar parallax (which would yield a more accurate determination of the size of the solar system). To do so, Gilliss established an observatory on Santa Lucia Hill in the middle of Santiago, Chile. This later became the National Astronomical Observatory of Chile, although it has twice moved to better locations.

The first observatory director noticed that the main instrument, an 6½” Fitz equatorial (third image), installed perfectly level, was constantly out of alignment, as if the hill itself were moving. At first, it was suspected that the hill was slowly rising due to undetectable earthquakes. Eventually, it was realized that the key to the phenomenon was that half of the hill was covered with sod and vegetation, and half consisted of raw dark basalt columns, exposed to the sun. During the day, the rock heated up and expanded, tilting the hill, until nightfall cooled things down. That was not an ideal situation for an observatory and was the reason for the first move to another location.

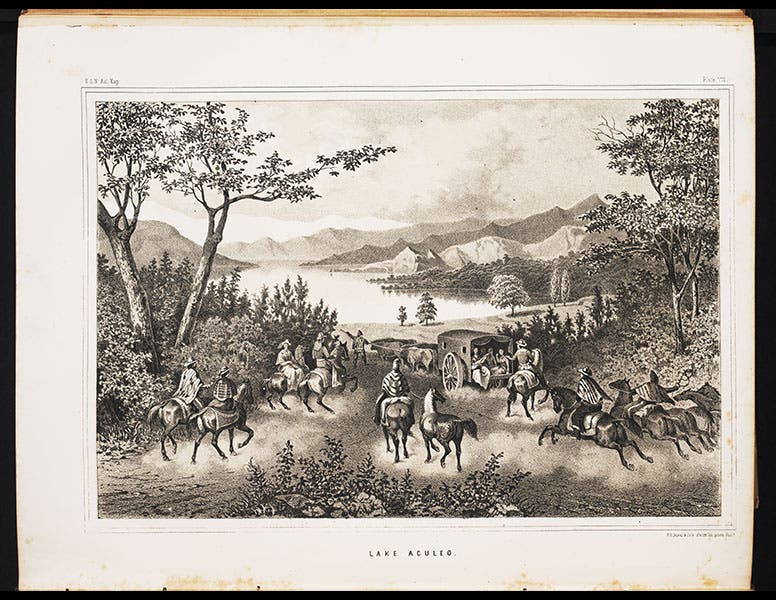

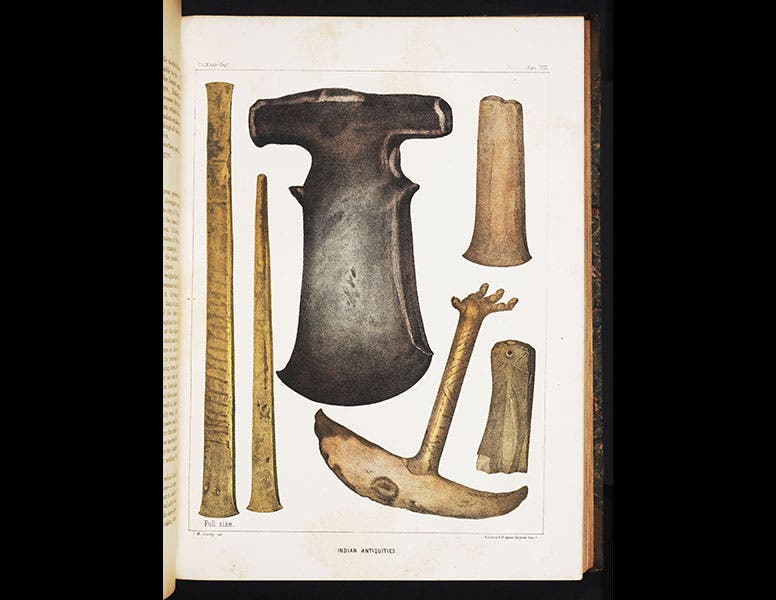

The U.S. Naval Astronomical Expedition was the United States’ second national scientific voyage, the first being the U.S. Exploring Expedition of 1838-42. Gilliss’s expedition not nearly as well-known as the famous U.S. "Ex Ex", which circled the globe and searched for a southern continent. The Gilliss expedition, which has no catchy nickname, followed the same kind of program, collecting the animals, plants, minerals, and artifacts of the countries they visited and observing native customs, in addition to performing their astronomical duties. After he returned in 1852, Gilliss wrote up a narrative, which was published in four volumes in 1855-56 (seventh image), with a star catalog issued later in 1870. The third volume was devoted to attempts to measure the solar parallax; the second volume discussed the natural history of the parts of South America that they visited. Each section of the natural history volume was written by specialists at the Smithsonian Institution, naturalists like Spencer Baird and John Cassin, the same people who wrote the natural history volumes for the narrative of the Ex Ex.

We have Gilliss's narrative, including the supplemental star catalog, in the Library; it has been resting unnoticed in our closed stacks, but we will be moving it promptly to the History of Science Collection where we keep our other scientific voyages. The images above were all taken from this work. The frontispiece to the narrative (first) volume shows Santa Lucia Hill before the observatory was built (first image); a gold-stamped vignette on the front cover depicts the same location after the observatory was installed (second image). There are also lithographs in this volume that show locals at work and play; we include one (fourth image). The natural history volume has a number of lovely lithographs, colored and uncolored; we show a parrot and some native artifacts.

Gilliss became director of the USNO when the Civil War broke out, as his predecessor went South. He died just before the war ended; he was 53 years old.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.