Scientist of the Day - James Macpherson

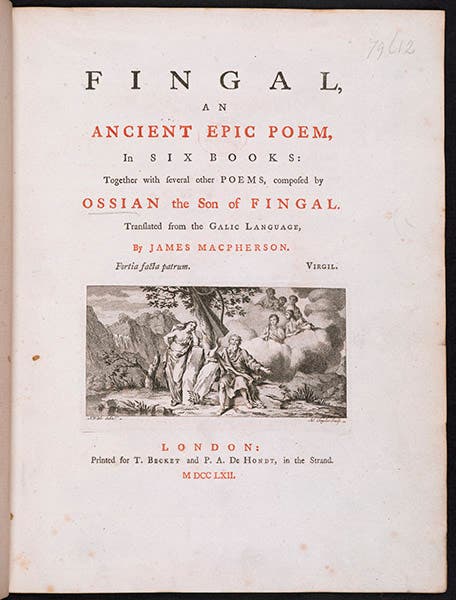

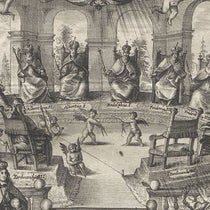

James Macpherson, a Scottish poet, was born Oct. 27, 1736. Although intended for the clergy, he dropped out of divinity school to try his hand at poetry, and he found himself attracted by ancient Scottish literature. As he toured through the highlands, he found – or claimed to have found – various manuscripts of a Gaelic poet named Ossian. One poem in particular concerned the exploits of Ossian’s larger-than-life father, Fingal. Mcpherson translated a number of the poems from Gaelic to English, including Fingal, and published the collection in 1762 as Fingal, an Ancient Epic Poem in Six Books. We do not own a copy; we show the titlepage from a copy in the British Library (second image).

The poem was an immediate sensation, providing the Scots with a hero similar to Homer's Odysseus (or perhaps North America’s Paul Bunyan). Some scholars were skeptical about it all – Samuel Johnson was the most outspoken critic, but others, such as David Hume, also voiced their doubts that Ossian ever existed, suspecting that the verse came from then pen of the not-so-ancient Macpherson instead. One of the main reasons for suspicion is that no one except Macpherson had ever seen any of the original manuscripts, and he was not forthcoming with this or any other evidence. Johnson made a trip to the Hebrides of Western Scotland, and in his account of his travels, A Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland (1775), he included many barbed comments directed at Macpherson and the supposed poet Ossian. He suspected that Macpherson simply fashioned his Fingal from the Irish and Scottish folk-hero Finn mac Cumhal, known as Fionnghall in Gaelic.

Nevertheless, Macpherson had many defenders, and one of them was Joseph Banks, the chief scientist on Captain Cook's first voyage around the world. When Banks, because of a disagreement with Cook, was not included in the second voyage, he set off in a huff for Iceland, with a stop in the Hebrides in 1772. When Banks discovered a large basalt cave on the isle of Staffa, a cathedral of stone fit for a folk hero, he promptly named it Fingal's Cave, and it has retained that name ever since (interestingly, Staffa is just off the isle of Mull, where Macpherson claimed to have found one of his Ossian manuscripts). We now know that the critics were right all along, that Fingal was a poem written by Macpherson and not by Ossian. But Fingal remains a celebrity among those with a Celtic background, and he still has a cave named for him, when he wants to get away.

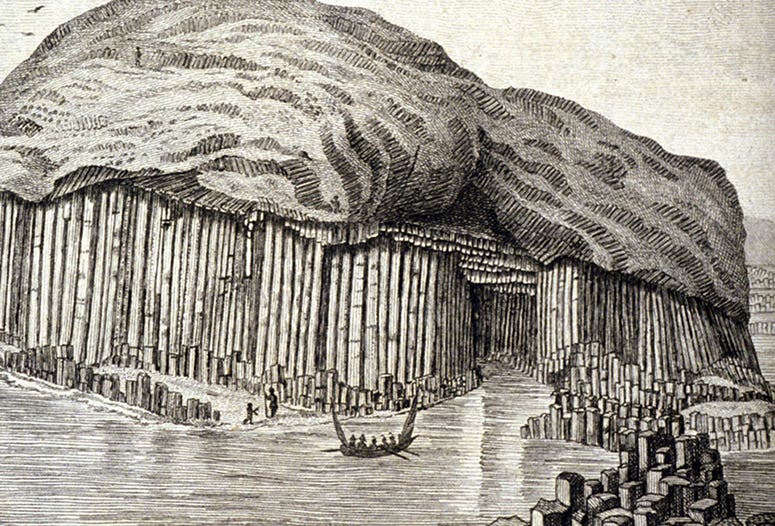

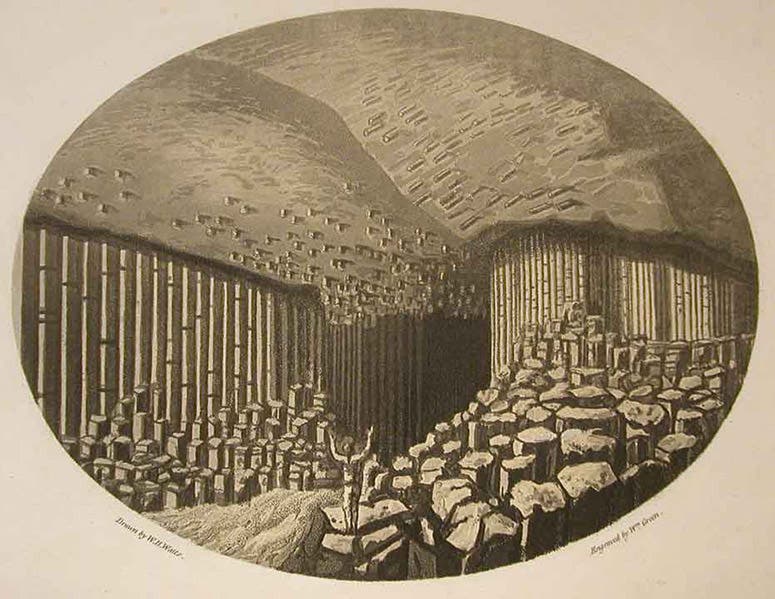

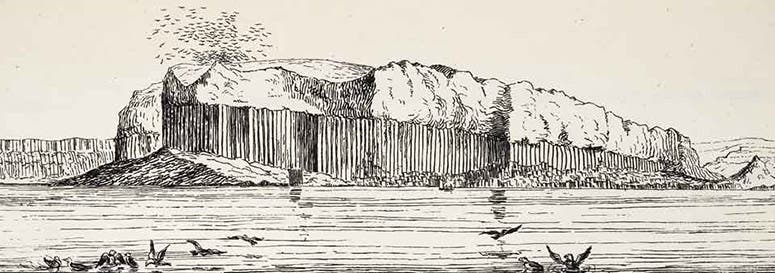

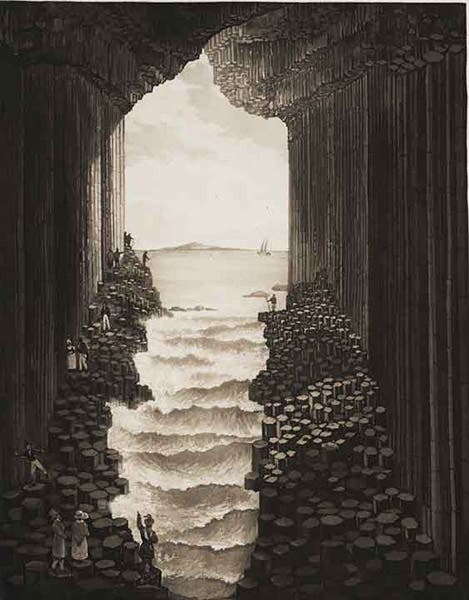

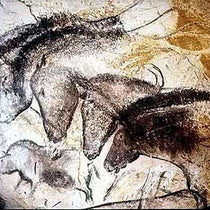

The reason we include Macpherson in the Scientist of the Day series is that it gives us a chance to show many of the wonderful illustrations of Fingal’s Cave and Staffa that we have in our history of science collections. We have these because Fingal’s Cave is a dramatic formation of columnar basalt, rivalling that of the Giant’s Causeway across the North Channel in Northern Ireland, and discussion of Fingal’s Cave was included in any geological text that discussed the origin of columnar basalt. Proceeding in chronological order, we begin with an engraving of the interior of Fingal’s Cave, drawn by Joseph Banks artist, John Cleveley, Jr., and loaned to Thomas Pennant for his book on Scotland and the Hebrides (third image). Most of the books we mention have 2 to 4 images of Staffa and Fingal’s Cave – we have chosen one from each except for the last. We have written posts on many of the individual authors, where you may find a few more images.

The French traveler and geologist, Barthélemy Faujas-de-St.-Fond, made a trip to the Hebrides in the 1790s, and in his Voyage en Angleterre, en Ecosse et aus Iles Hébrides (1797), he included several views; we show one of the Isle of Staffa (fourth image, above). About the same time, Thomas Garnet made a tour of Scotland and the Hebrides, and his book (1800) includes aquatints of Staff and the surroundings isles. His interior view of Fingal’s cave is odd but charming, with what appears to be a conductor standing on the rocks, coordinating the sounds of the waves as they crash in and out of the cave (fifth image, just above)

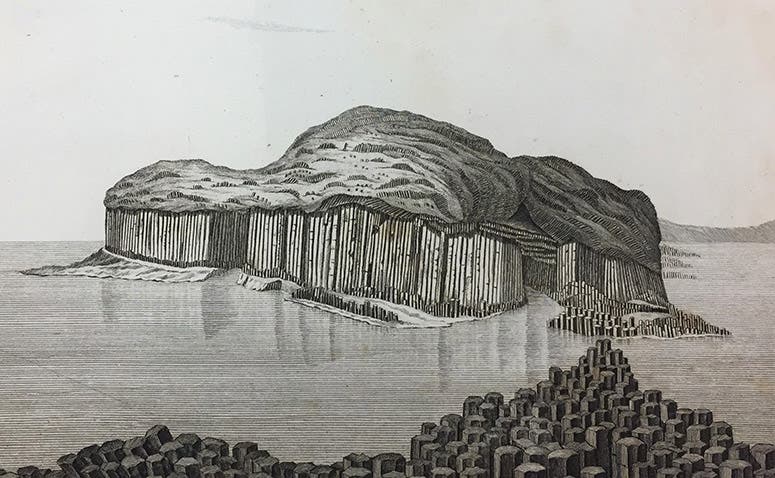

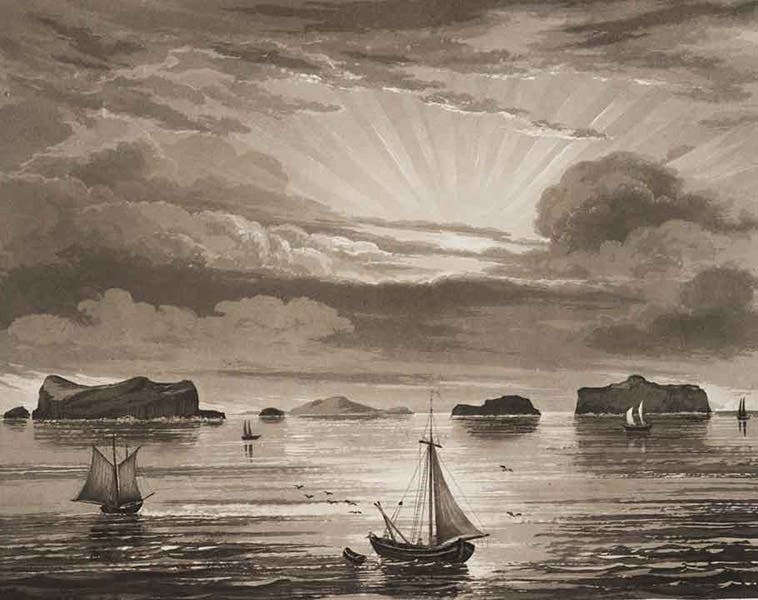

Scipione Breislak was an Italian geologist who published a series of views of basaltic formation from all over Europe in 1818, including several of the Hebrides. We show his engraving of Staffa from a distance (sixth image, just above). Henry de la Beche was an English geologist who in 1830, published his own set of views of geological phenomena, including Staffa and Fingal’s cave. We show his line lithograph of Staffa (seventh image, just below).

Our finest set of illustrations of Fingal’s Cave comes from Charles-Louis-Fleury Panckoucke, a French printer, who wrote an entire book on Staffa and “la grotte basaltique,” as he called Fingal’s Cave, in 1831. We include two of his aquatints here – of the cave (eighth image, just below), and of Staffa and nearby isles (ninth image, below).

Finally, we are reminded by Garnet’s image of the conductor in the cave (fifth image) that Felix Mendelssohn visited Staffa in 1829 and was immediately moved to set the scene to music. Fingal’s Cave: An Overture, premiered in 1832. I selected a video of the 10-minute performance with some modern still photos of Staffa and Fingal’s Cave. It is hard to doubt the existence of Ossian and Fingal when you listen to Mendelssohn’s evocative overture while viewing the photos (which however aren’t nearly as appealing as our vintage prints).

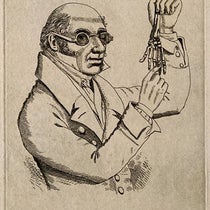

Macpherson may have been a bit of a fraud, but he is buried in Westminster Abbey, and he has a vivid portrait by George Romney hanging in the National Portrait Gallery in London (first image). He must have done something right.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.