Scientist of the Day - James Mackintosh

Sir James Mackintosh, a Scottish jurist and political writer, was born Oct. 24, 1765. Mackintosh received a medical degree from the University of Edinburgh, but he found his true calling in the aftermath of the French Revolution, when Edmund Burke published Reflections on the Revolution in France (1791), a conservative manifesto, defending the British way of doing things, to which Mackintosh responded with Vindiciae Gallicae: A Defence of the French Revolution and its English Admirers (1791), which established the definitive Whig position on both political revolutions and the British constitutional monarchy. The book was well received, preferred by some to Thomas Paine’s The Rights of Man, so Mackintosh read for the bar and left medicine behind. He had a long and successful career as lawyer, judge, member of Parliament, and professor of law.

To a historian of science, the life of Mackintosh is not particularly interesting or relevant, although his manner of shuffling this mortal coil was not lacking in drama, since he choked to death on a chicken bone, taking a full month to do so. Francis Bacon, you might recall, also died because of a chicken, although in his case, he was trying to preserve one in snow before he caught pneumonia. Other resemblances between Mackintosh and Bacon the scientist are distinctly lacking.

But Mackintosh did one special act of kindness that redeemed everything and should guarantee free passage at the pearly gates – he gave young Charles Darwin a badly needed shot of confidence. Darwin, age 18, had just dropped out of the University of Edinburgh, where he went with hopes of becoming a physician like his father. Those hopes were now dashed, and the plan was to send Charles off to Cambridge to enter holy orders and become a country parson, a career that required no aptitude whatsoever. Before heading off to the fens, Darwin visited Maer Hall in Staffordshire, the estate of his uncle, Josiah Wedgwood, not too far from Darwin's home in Shropshire (second image). And there he met Sir James, who had apparently been invited up from London by Wedgwood. Forty years later, when he wrote down his autobiography, Darwin recalled the encounter with unusual clarity:

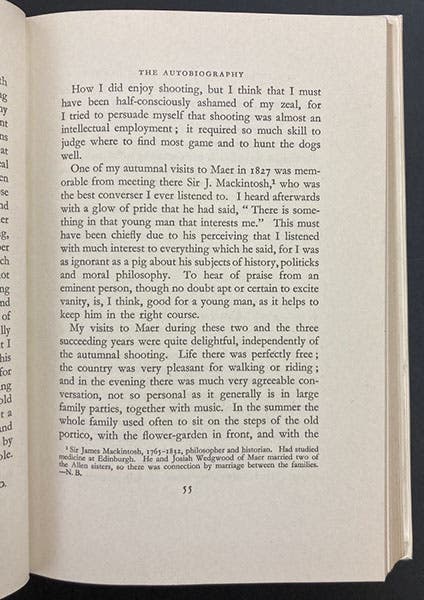

One of my autumnal visits to Maer in 1827 was memorable from meeting there Sir J. Mackintosh, who was the best converser I ever listened to. I heard afterwards with a glow of pride that he had said, "There is something in that young man that interests me." This must have been chiefly due to his perceiving that I listened with much interest to everything which he said, for I was as ignorant as a pig about his subjects of history, politicks & moral philosophy. To hear of praise from an eminent person, though no doubt apt or certain to excite vanity, is, I think, good for a young man, as it helps to keep him in the right course.

Paragraph discussing James Mackintosh, in The Autobiography of Charles Darwin, 1809-1882, ed. by Nora Barlow, Collins, 1958 (author�’s collection)

Darwin had been praised by somebody famous, for no particular reason, but that didn't matter. An important gentleman thought he might amount to something, and said so to his uncle. And Darwin never forgot it. We all need this when we are growing up, at some point, often at several points, and it really does seem to have an effect. So if you have young people in your personal circle, and one of them seems to be foundering, find an occasion for praise. You might inspire a future recollection like Darwin's.

Front dust jacket, The Autobiography of Charles Darwin, 1809-1882, ed. by Nora Barlow, Collins, 1958 (author’s collection)

Darwin’s Autobiography was first published in 1887 as part of his Life and Letters, edited by his son Francis, and then published separately in 1929 and 1950. These versions were all bowdlerized to some extent. In 1958, Darwin’s granddaughter Nora Barlow published the first edition faithful to Darwin’s manuscript, with no expurgations, and it is from this edition that we extract the passage on Mackintosh (third image). The Library owns all the editions of Darwin’s Autobiography, and as best I can tell, the Mackintosh paragraph is the same in all of them.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Using an astrolabe to measure the depth of a well, woodcut in Elucidatio fabricae vsusq[ue] astrolabii, by Johannes Stöffler, 1513 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/a998eb50-55d2-4a88-ace2-a50aa5fa86e7/Stoffler%201.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)