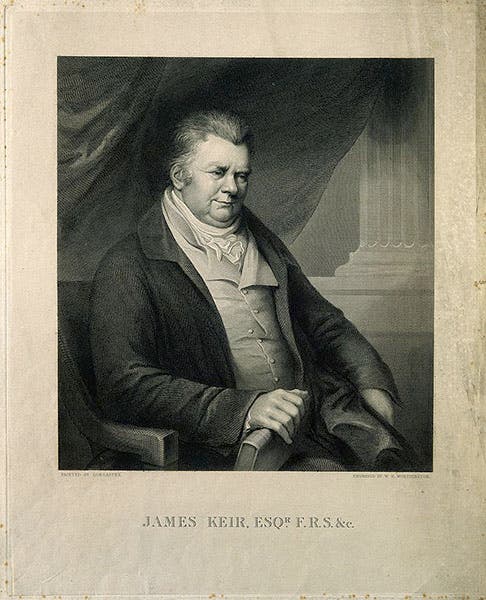

Scientist of the Day - James Keir

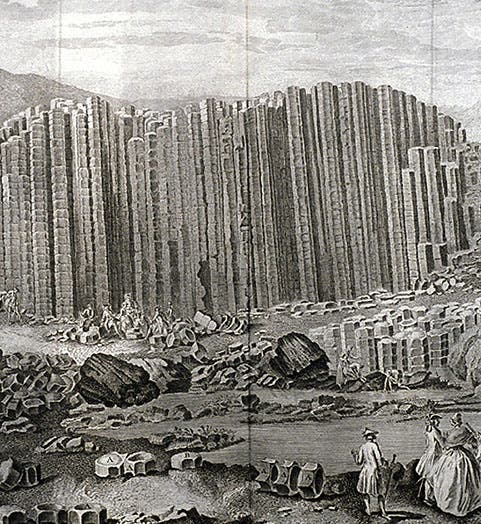

James Keir, a Scottish chemist and manufacturer, was born Sep. 29, 1735. Keir was yet another member of that gather-by-night philosophical club, the Lunar Society of Birmingham, which we have mentioned quite a few times in these posts, when celebrating the birthdays of members such as the physicians Erasmus Darwin, William Small, and Wlliam Withering; the inventor James Watt, the geologist John Whitehurst, and the artist Joseph Wright (we have yet to feature industrialist Matthew Bolton and the potter Josiah Wedgwood). Keir owned and/or managed a series of manufacturing firms (even running Boulton & Watt's steam engine factory for a period), but it was early on, in 1776, while managing a glass factory, that he made his most important scientific discovery. He was doing experiments with molten glass, wondering how the final product might be affected by the rate of cooling. He found that if the molten glass were cooled very slowly, it did not become glass at all, but assumed a crystalline structure, like fine-grained basalt. Now at the time, a controversy concerning basalt was simmering in geological circles, with many geologists, such as the great German mineralogist Abraham Werner, arguing that the crystal structure of basalt could only be achieved by deposition from water. Keir, in a paper published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in 1776, argued that his experiments indicated that basalt is an igneous rock, cooled directly from a molten state. He even suggested that places with extensive basalt formations, such as the Giant's Causeway in Ireland, or Fingal's Cave in Scotland, were formed by volcanoes long since vanished. James Hutton would come to similar conclusions about basalt in his Theory of the Earth (1795).

We exhibited Keir's insightful paper in our 2004 exhibition, Vulcan's Forge and Fingal's Cave, where, since the paper lacks illustrations, we showed the page where Keir offered his daring conclusions about the origin of the Giant’s Causeway and Fingal’s cave (“the pillars of Staffa”). In the same exhibition we showed quite a few engravings of those two formations. We use an engraving of the Giant’s Causeway, after a painting by Susanna Drury, as our opening image; here is another from the exhibition, as well as one each of Staffa, home of Fingal’s Cave, and the cave itself. There are few portraits of Keir; the one we show here is an engraving by W. H. Worthington, after a lost painting by L. de Longastre, that is in the Wellcome Collection in London. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.