Scientist of the Day - James Hutton

James Hutton, a Scottish geologist, was born June 14, 1726, in Edinburgh. Of the many persons who have been awarded the title of “Father of Geology,” Hutton is the most deserving, in our opinion. While nearly all of his contemporaries argued that the earth had been shaped by catastrophic floods, Hutton believed that small forces, such as erosion and uplift, acting over long periods of time, could create all the changes we see on the earth’s surface. This doctrine, set forth first in a paper in 1788, and more fully in a two-volume book of 1795, and known afterwards as uniformitarianism, eventually became one of the fundamental pillars of earth science, especially after it was adopted by Charles Lyell in the 1830s.

Hutton further argued that certain rocks, such as basalt and granite, had cooled from a molten state, and were not laid down from aqueous deposits as others maintained. This proposal came to be known as plutonism, and Lyell accepted it as the other pillar of his Principles of Geology (1830-33).

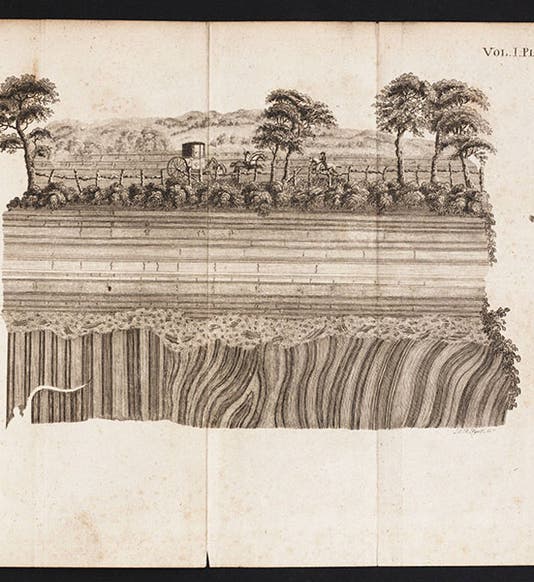

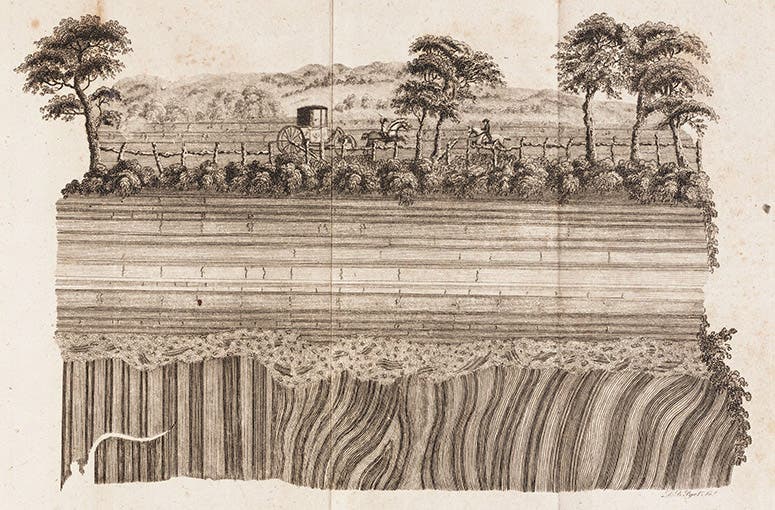

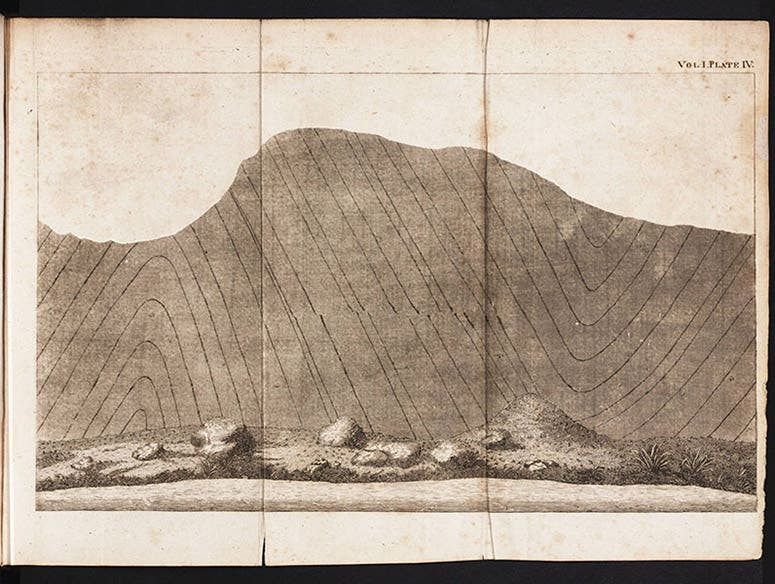

One of the formations that Hutton discovered that demonstrated his geological views was at Jedburgh in Scotland, where there is a layer of horizontal sedimentary rock that sits directly on metamorphic rock whose strata are vertical. Clearly the lower rock was laid down, uplifted, slowly tilted to a vertical position by forces within the earth, and then subsided, so that additional sediments could be deposited horizontally onto and compressed into rock. There must be an immense gap in time between the formation of the two sets of strata. Hutton named such a gap an “unconformity,” and the Jedburgh formation is commonly referred to as the “unconformity at Jedburgh.” It was depicted on a plate in vol. 1 of his Theory of the Earth (first image). Hutton found another unconformity at Siccar Point on the coast, which is more accessible. Hundreds of geologists every year make a pilgrimage to Siccar Point to see where the modern science of geology began.

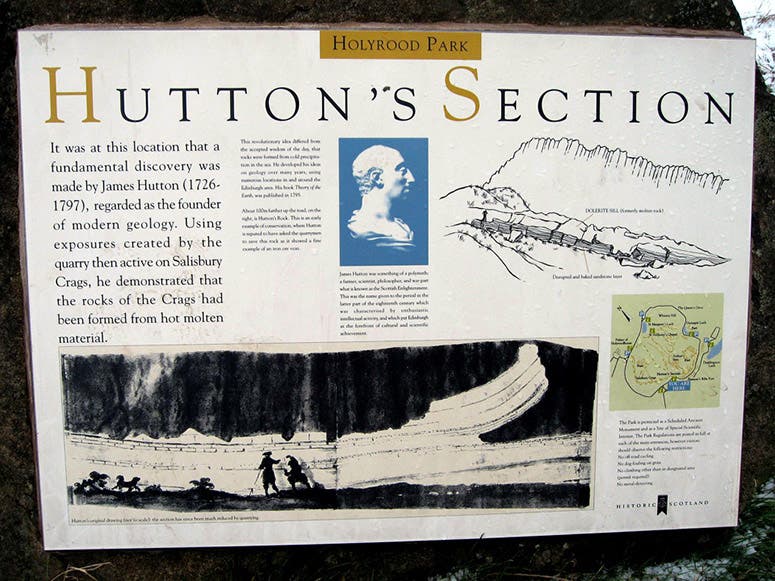

Hutton found another site, closer to home, that demonstrated that basalt (which was usually called “whinstone” in Scotland) was not sedimentary in origin, but had cooled from a molten state. Just outside Edinburgh is a cliff called Salisbury Crags, which consists of whinstone sitting on top of a horizontal bed of limestone. Hutton found a location at the bottom of the whinstone where the limestone beneath had actually been melted, with some of it floating up into the basalt, indicating that the whinstone was molten when it was first injected over the limestone. The spot has come to be known as Hutton’s Section, and there is a plaque indicating its location within Holyrood Park. We show you the plaque (fifth image), and a view of Hutton’s section as it appeared in a geological book of 1838 by Robert Cunningham (perhaps including a silhouette of Hutton himself, sixth image). If hundreds of geologists make a special trip every year to Siccar Point, thousands make the walk along Radical Road to see Hutton’s Section. Or they did, until Historic Environments Scotland closed the road in 2018 after a rockfall and has kept it closed for the last four years, to the great consternation of geological tourists everywhere.

In our next post on Hutton, we will look at his paper of 1788, which appeared in the first volume of the Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, and also examine the immediate reception of uniformitarianism and plutonism. Meanwhile, you can read already existing posts on James Hall, who did experiments in 1798 to prove that whinstone is an igneous rock, and John Playfair, whose Illustrations of the Huttonian Theory of the Earth (1802) did much to help disseminate Hutton’s ideas. You can also check our post on John Clerk of Eldin, who travelled with Hutton on his forays through Scotland and whose sketches, which still survive, were used by Hutton for his book. The drawing in the plaque posted at Hutton’s section was taking from a Clerk sketch, which we reproduce in our post.

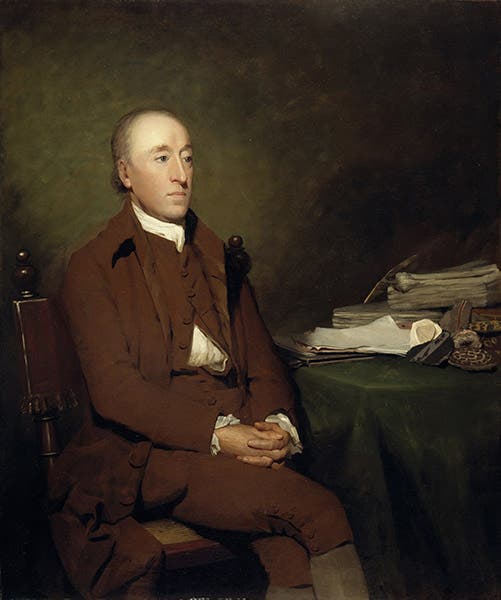

Our portrait of Hutton was painted by Henry Raeburn, who, since he painted portraits of many Scottish scientists, was treated to his own post back in 2015.

This is a revision of a post that first appeared on June 14, 2016. The text has been greatly expanded, two new images have been added, and captions have been included for all images.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Using an astrolabe to measure the depth of a well, woodcut in Elucidatio fabricae vsusq[ue] astrolabii, by Johannes Stöffler, 1513 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/a998eb50-55d2-4a88-ace2-a50aa5fa86e7/Stoffler%201.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)