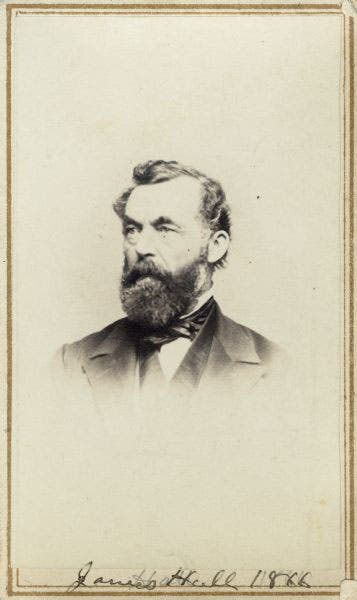

Scientist of the Day - James Hall, Jr.

James Hall, Jr., an American geologist and paleontologist, was born Sept. 12, 1811, in Hingham, Mass. He attended the new Rensselaer College in Troy, New York, with its novel teaching practices that involved hands-on laboratory training for students, and studied under noted geologists Amos Eaton and Ebenezer Emmons. After he graduated, Hall stayed on to teach until 1836, when the state legislature of New York authorized a natural history survey of New York state, one branch of which involved geology, and another paleontology. The state was divided into four geological districts, and Hall was originally assigned to assist Emmons in the survey of the second district, but he demonstrated such promise that he was soon given the fourth district for himself. This district covered western New York, including Niagara Falls.

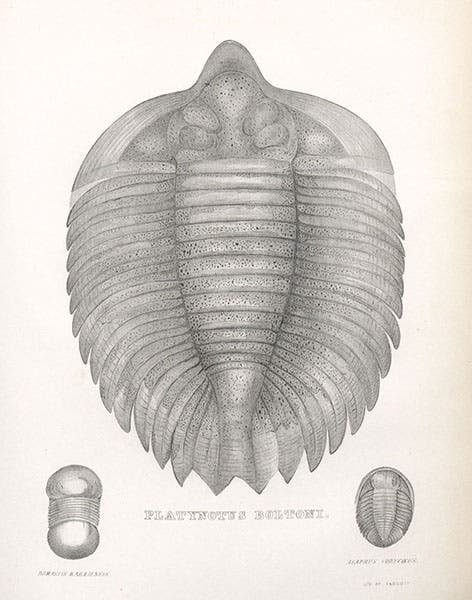

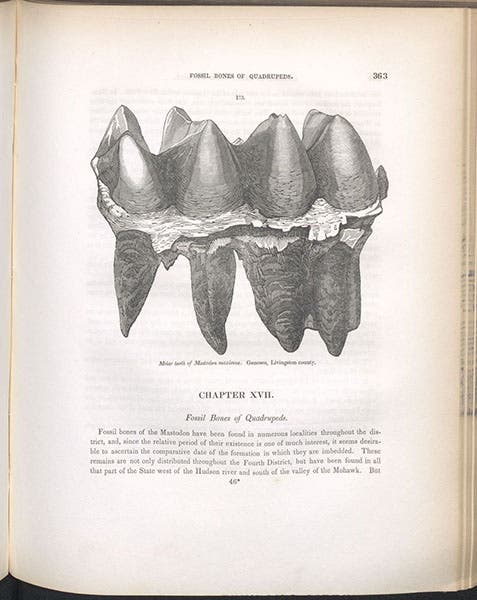

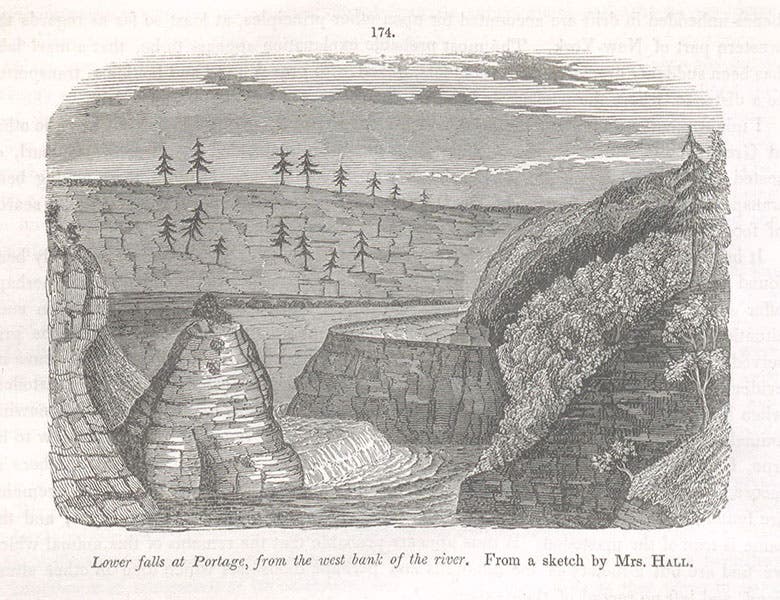

Each district head was responsible for publishing a volume on the geology of his district, and Hall's was published in 1843, as The Geology of New York, Pt. IV: Survey of the Fourth Geological District. It was (and is) a very attractive volume, with many woodcuts scattered throughout the text, and an abundance of plates at the end. Many of the woodcuts are scenic vignettes – some of them provided by Hall's wife, which are signed "Mrs. Hall" (fifth image). Other illustrations are more elaborate, and are either engraved, or lithographed, such as the bird's eye view of Niagara Falls (third image), or the beautiful trilobite fossil, a full-page plate bound in at the back (first image).

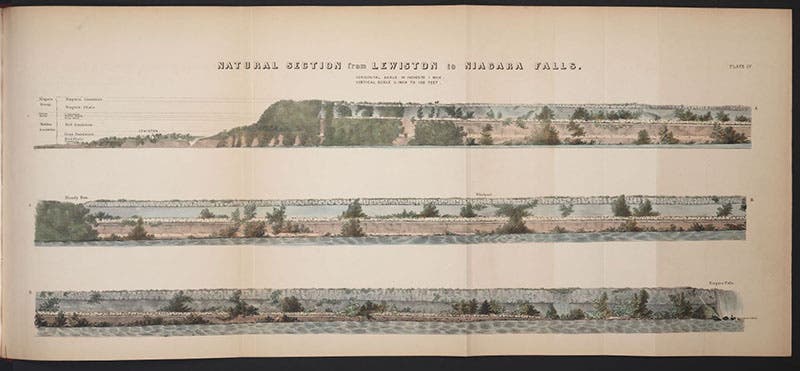

The volume also contains quite a few sections, or imaginary cuts through the landscape, to show the stratigraphy of an area, a convention pioneered by English geologist William Smith in 1816. We include one of those sections here (sixth image), stacked up on three levels, and showing a cut from Lewiston south to Niagara Falls, a distance of only about 10 miles. Lewiston is at upper left; you can see the falls at the lower right.

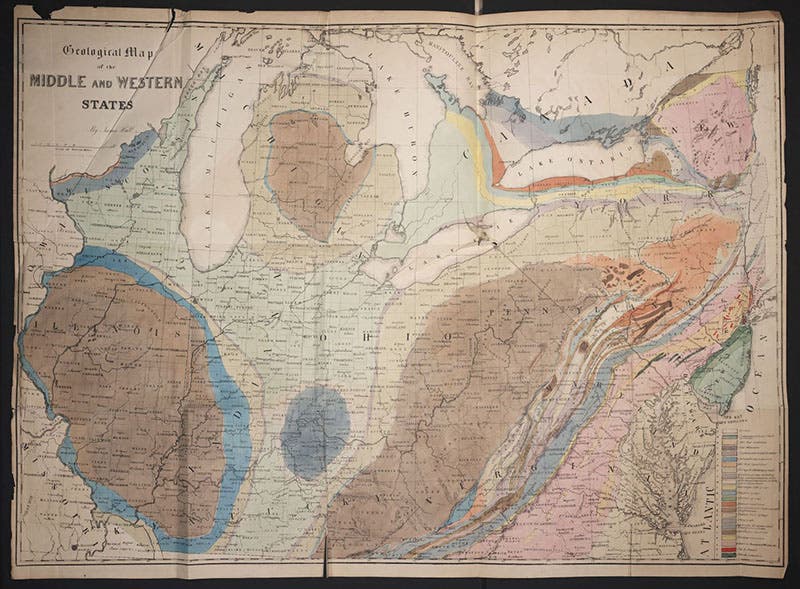

One of the plates at the end is a large folding colored map, “Geological Map of the Middle and Western States” (seventh image). When Charles Lyell, the eminent English geologist, came to visit the United States in 1841-42, Hall showed him his map, not yet published, and Lyell managed to copy it and later publish it in his own Travels in North America (1845). Hall wrote an anonymous letter to a Boston newspaper, denouncing Lyell for pirating the map. Lyell must never have discovered who wrote the letter (which Hall soon regretted writing), for Lyell and Hall remained friendly until the end of their lives.

Hall also published The Paleontology of New York, which, unlike the single-volume Geology, extended over 8 parts in 13 volumes and took 47 years to compile and print (1847-94). We have the complete set. We don't show you any images from this work, for we have a policy in place that requires our digital services unit to scan any work that we feature in our Scientist of the Day series, and I couldn't see asking them to scan a 13-volume work, just so I could use one image, when I could get by nicely with just the one-volume Geology.

Hall was always at odds with the New York state legislature over funding, and they regularly suspended his salary (he had the position of State Paleontologist), so Hall farmed himself out to other state geological surveys, including that of Iowa, Illinois, and Wisconsin. He helped write many of their reports, although he generally stayed in Albany to do so.

Hall was, by all accounts, cantankerous and hard to work with, but by the 1860s, he was the most celebrated geologist and paleontologist in the United States. He was a founding member of the National Academy of Sciences and the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and the first president of the Geological Society of America. He set up his own teaching laboratory in Albany and taught most of the next generation of American geologists. He invented the concept of the geosyncline, explaining how the buildup of sediment causes neighboring regions to rise to become mountains. When he was 85 years old, he travelled to St. Petersburg, Russia, to attend an International Geological Congress there, which I find remarkable. After he died in 1898, just shy of his 87th birthday, he was buried in Albany Rural Cemetery, Menands, New York, where you can still see his tombstone (eighth image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.