Scientist of the Day - James Dwight Dana

James Dwight Dana, an American geologist, was born Feb. 12, 1813, in Utica, New York. He was exactly 4 years younger than Charles Darwin, who was born on Feb. 12, 1809, and their careers followed striking parallels. Both went on scientific voyages, Darwin on the Beagle, 1831-36, and Dana on the U.S. Exploring Expedition, 1838-42. Both wrote their first geology books on coral reefs, Darwin in 1842, Dana in 1853. Both also made intensive studies of crustaceans, Darwin specializing in barnacles, Dana on the entire class. They never met, but they corresponded, about coral reefs and barnacles, and seemed to respect one another. On the topic of evolution, they differed greatly, and we will come back to that.

There were other differences. Darwin was independently wealthy and more or less a recluse; Dana was an academic and socially active. He had studied under Benjamin Silliman at Yale, and not only did he succeed Silliman, he married Silliman’s daughter. Dana wrote textbooks, which Darwin never did, mostly on mineralogy, and these were astonishingly successful; one of them is still in print, in its 22nd edition or so.

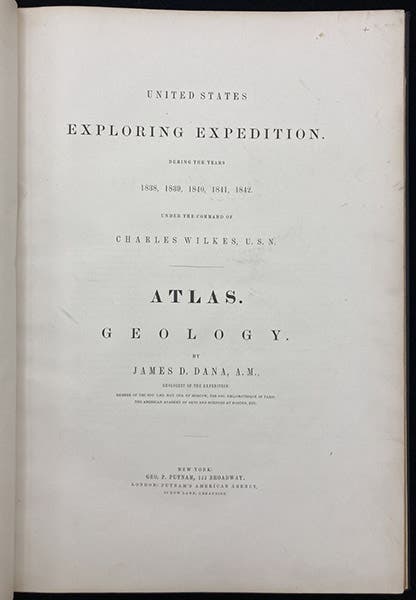

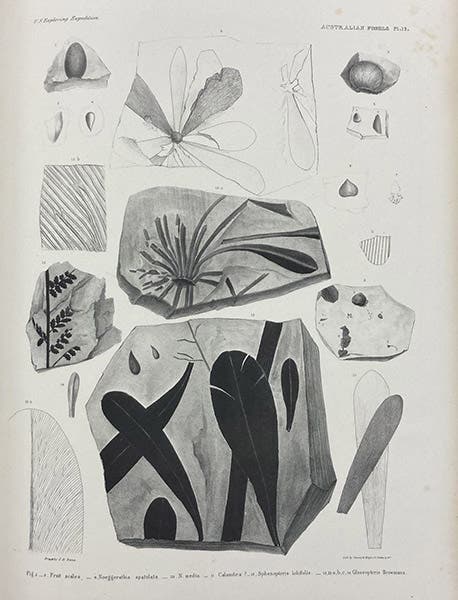

Dana’s participation in the United States Exploring Expedition (often referred to as the “US Ex Ex”) deserves special comment. Dawin had been a supernumerary on HMS Beagle, a guest of Captain Fitzroy, with no official duties. Dana was one of nine official “scientifics” on the US Ex Ex, invited to join Lieut. Charles Wilkes on an exploration of the south Pacific. His field of expertise was geology, but when the invertebrate zoologist left the expedition, Dana picked up that as well. Dana studied volcanoes wherever the expedition went, which included some of the first examinations of the Cascade mountains on the northwest coast, and of Hawaii. He correctly concluded that, unlike Hawaii’s volcanoes, the Cascade volcanoes were young, and that Mt. St. Helens had been active in very recent memory. Dana collected numerous fossil invertebrates and plants from all over. After they returned, Dana spent the next 7 years writing up the geological results of the expedition and publishing the massive volume 10: Geology, with an accompanying Atlas of 21 plates, all of which he drew himself. We show a plate that illustrates the fossils of Glossopteris browniana, a Permian seed fern with tongue-shaped leaves (glosso is tongue in Latin), that is presumably named after Robert Brown, a botanist at the British Museum.

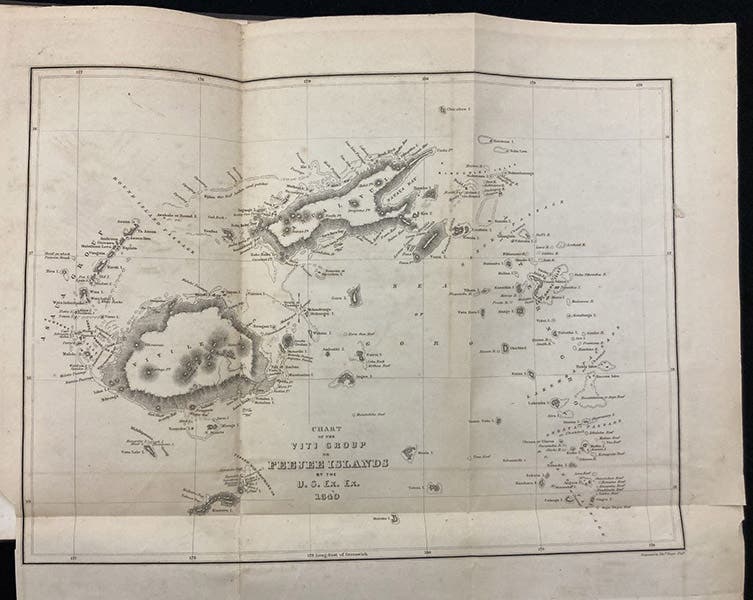

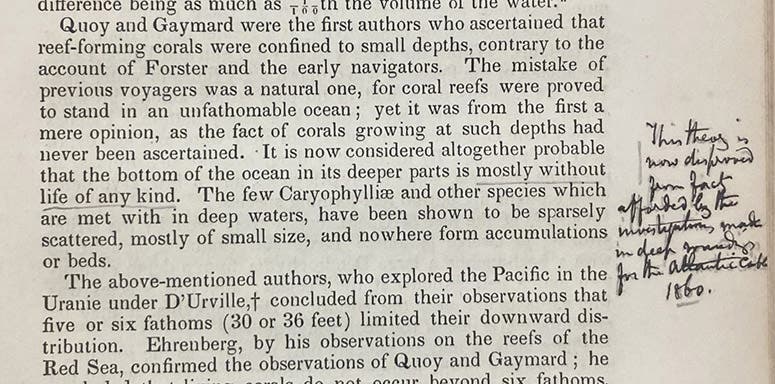

After Geology came out, Dana published, in 1853, a treatise drawn from the section on coral reefs, which we have already mentioned (fourth image). It contains a map of the coral formations in the Fiji Islands (fifth image). I was also struck by the fact that our copy was annotated by an early reader (sixth image). It was believed in the 1850s that the deep sea was devoid of life, and Dana says as much, following the conclusions of Edward Forbes. The annotator notes that when they laid the Atlantic cable in 1860 [sic], they found life in deep-sea soundings.

But back to Dana and Darwin. Dana had some disagreements with Darwin on the subject of coral reefs. Darwin was the first to realize that coral reefs and atolls were the result of corals growing up on submarine volcanoes as they gradually subsided, and he published this in 1837. Dana had trouble giving Darwin the credit for being first, and he liked to pretend (even in print) that he discovered the same thing independently. It also miffed Dana that he saw many more coral formations on his trip across the Pacific than Darwin ever did, and yet Darwin got it right. But where they really disagreed was on the subject of evolution by natural selection.

Dana grew up with a firm belief in design, embracing the Platonic idea that each creature was a variation on a divine form that was pre-established by God. It was very difficult for people with such a mindset to suddenly abandon the idea of design, and welcome the random chaos of evolutionary descent. It took Dana over twenty years to convert, and then he did so grudgingly. Interestingly, he refused to read Darwin's book for over 4 years, even though Darwin had sent him a presentation copy, which irritated Darwin no end, since Dana was publicly criticizing Darwin’s ideas without actually reading them. Darwin seldom rebuked people he considered friends, but he did so with Dana, telling him in a letter that he should really read the Origin before attacking it.

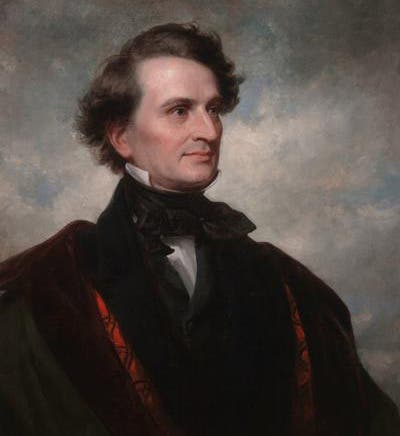

Dana died on Apr. 14, 1895, at age 82. He is remembered by a fine oil portrait in the Yale University Art Museum, executed by Daniel Harrington (first image), who did a fine portrait of Benjamin Peirce about the same time (which you can see at our post on Peirce). Dana is also a living memory in Yosemite National Park in California, where the second highest mountain in the park is named after him (sixth image). The tallest mountain, by 53 feet, is fittingly named after Charles Lyell, a geologist far more influential than Dana, although he too took his time accepting Darwinian evolution.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Using an astrolabe to measure the depth of a well, woodcut in Elucidatio fabricae vsusq[ue] astrolabii, by Johannes Stöffler, 1513 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/a998eb50-55d2-4a88-ace2-a50aa5fa86e7/Stoffler%201.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)