Scientist of the Day - James Cowles Prichard

James Cowles Prichard, an English physician and ethnologist, was born Feb. 11, 1786, in Ross-on-Wye, Herefordshire. Prichard was raised as a Quaker, which meant his educational opportunities were limited. He was educated at home, and having chosen medicine as a future profession, he took various apprenticeships, and finally headed for the University of Edinburgh, where his religion was not a problem, and which had a fine medical school to boot. Upon completion of his medical degree in 1808, Prichard, unusually, left the Quaker community to become an Anglican. His family had relocated to Bristol when he was young, and Prichard moved there to establish a medical practice and work at the Bristol Infirmary, moving into the Red Lodge nearby, a venerable Elizabethan house that is now a museum.

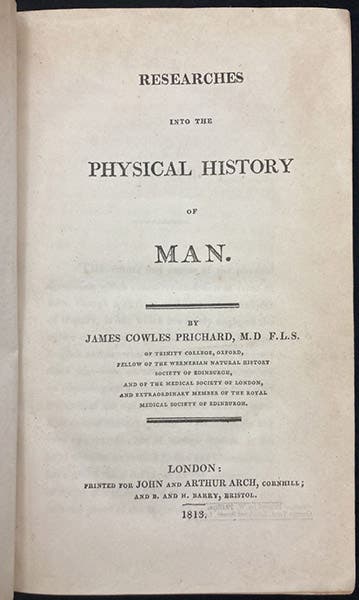

Prichard had written his doctoral thesis on the races of mankind, and in 1813, he molded his thesis into his first book, Researches into the Physical History of Man, in which he argued for the unity of the human species. He drew his arguments from all sorts of disciplines, including zoology, anatomy, linguistics, even the study of diseases, and he was adamant in his conclusions that all humans races were part of one large family (and, not incidentally, that all were descendants of Adam, tarred by original sin, and capable of salvation).

Prichard’s book was very popular, prompting a second edition, in 2 volumes, in 1826, and a third edition, now expanded to 5 volumes, in 1837-45, and a fourth edition after that. Charles Darwin met Prichard at the BAAS meeting in Birmingham in 1839, and subsequently, he read his book, presumably the second edition. Darwin accepted Prichard’s thesis but would later give the unity of humankind an evolutionary explanation. We have only the first edition of 1813 in our collections, so I am not sure what kinds of revisions Prichard made to expand his dissertation into a 5-volume encyclopedia.

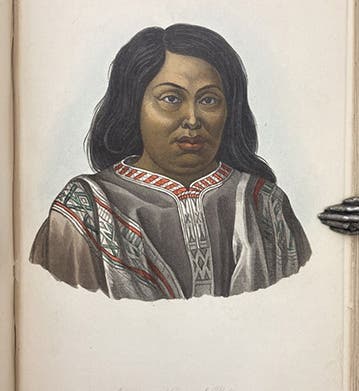

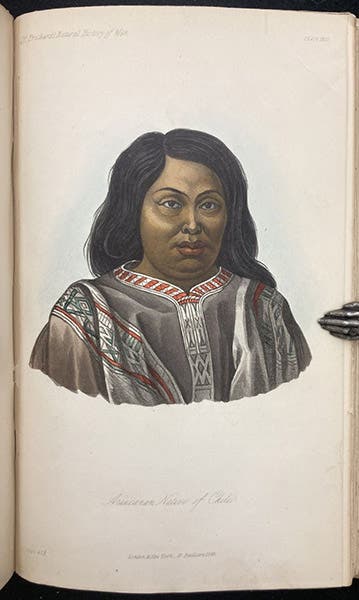

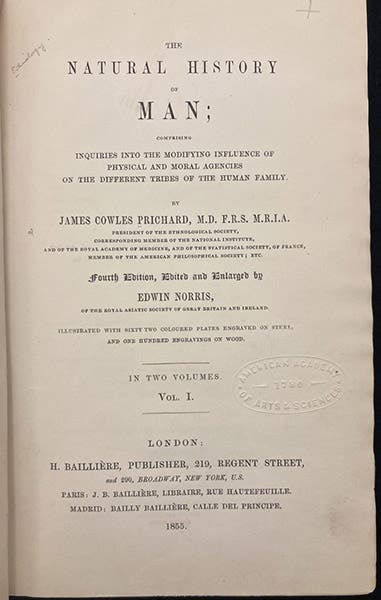

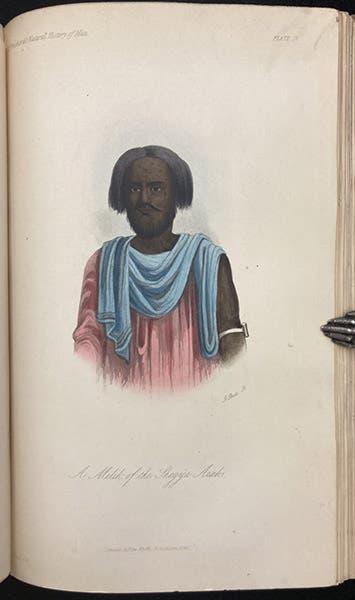

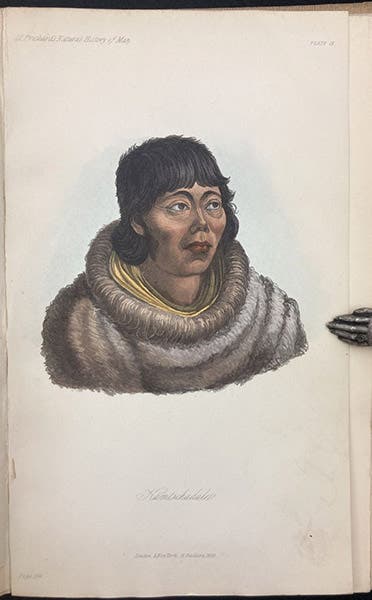

Prichard wrote a second book in 1843, called the Natural History of Man (third image). This was a more detailed examination of the various races of humans that can be found around the globe, bolstered by fine hand-colored lithographs of members of a variety of ethnic groups. Prichard was not a traveler, so most of his information was gathered from travel narratives, of which there were an abundance in the first half of the 19th century. We have only the fourth edition of his book, printed in 2 volumes in 1855, and all of the ethnographic images included in this post were drawn from our copy of the fourth edition. As you can see, the hand-colored lithographs are beautiful.

Prichard’s books were widely debated and attacked in an era when England had banned slavey, and defenders of the lifestyle of the southern United States, such as Josiah Nott, were looking for reasons not to. Prichard was especially vocal about the need to save indigenous peoples, such as the Tasmanians, from extinction. His efforts were not heeded in time to save many threatened peoples and their languages.

Prichard moved to London in 1845 to help oversee insane asylums there, whereupon he was invited into the Royal Society. But he died in 1848 of rheumatic fever. There is a blue plaque on the Red Lodge in Bristol, commemorating his time there.

Oddly, there is no portrait of Prichard in the National Portrait Gallery in London, nor is one included on ArtUK. The only portrait that anyone ever sees is the one on Wikipedia (second image), which comes from some early 20th century book and is hardly contemporary. I suppose it is better than nothing, but it is not better by much.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.