Scientist of the Day - James Cook

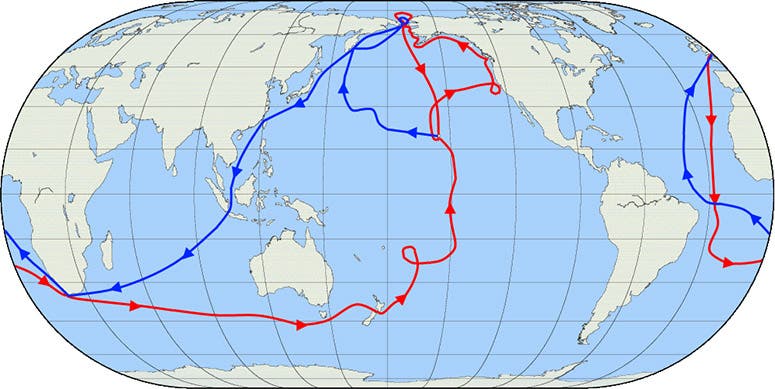

James Cook, a British naval commander and explorer, was born Nov. 7, 1828, in Yorkshire, and grew up in Whitby, a port and ship-building center on the northeast coast of England. Cook made three circumnavigations of the globe, the first in 1768-71, which we discussed in our first post on Cook; the second, which attempted to find a southern continent, from 1772-75, which we included in our second post. Today we look at his third and last voyage, which lasted from 1776 to 1779 for Cook, and until 1780 for those that made it back to England.

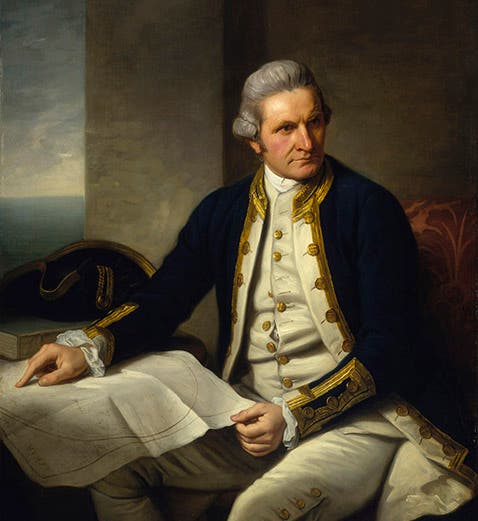

The purpose of Cook’s third voyage was ostensibly to return Omai, a Polynesian from the isle of Raiatea, to his homeland; he had come to England on the return voyage of the Adventure, one of Cook's ships on the second circumnavigation. In fact, there was a secret agenda for the third voyage: to sail up to the newly discovered Bering Strait and see if they could find a northwest passage from the Pacific side. Cook, who had only been back home for 7 months, was provided with two ships: HMS Resolution, his Whitby-built flagship from the second voyage, and a newer ship, the Diligence, another Whitby-built collier (coal-ship), that was renamed HMS Discovery. The Resolution had a crew of 86; the Discovery, 70. There was no naturalist of the stature of Joseph Banks (first voyage) or Johann and Georg Forster (second voyage); instead, the surgeon William Anderson doubled as naturalist. They did have a ship's artist, John Webber, who provided many of the visual records of the voyage, including a portrait of Cook that we showed in our second post.

The fleet of two sailed from Plymouth on July 12, 1776, just 8 days after the American colonies had declared their independence from Great Britain. Cook sailed to South Africa, picked up provisions, and then headed across the southern Pacific to Tasmania. On the way, they stopped at the newly discovered Kerguelen islands, far south in the Indian Ocean, and as they arrived on Christmas Eve, their sheltering harbor was named Christmas Harbor. It would be much visited by later voyages to Antarctica. They discovered there and harvested a new plant, Kerguelen cabbage, which, as it turned out, was an anti-scorbutic and kept scurvy at bay for the long sail to Australia. From Tasmania, Cook’s ships sailed to New Zealand, and then north into Polynesia, headed for Tahiti, but encountering other island groups on the way – the Friendly Islands, the Society Islands, and a newly discovered group, soon named the Cook Islands.

By August of 1777, they had made it to Tahiti, and Omai was returned to his native island, where the crew built him a house with garden. Cook and the crew did their best to be tolerant of Tahitian customs that they had missed the first time around, but they were sorely tested when they discovered that the Tahitians practiced human sacrifice, and occasional cannibalism. Cannibalism was common on many of the Polynesian island groups, to the consternation of the crew.

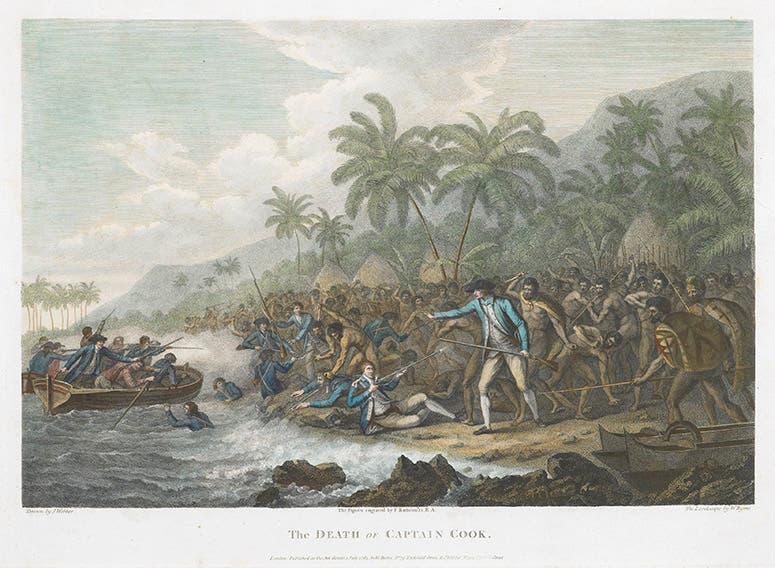

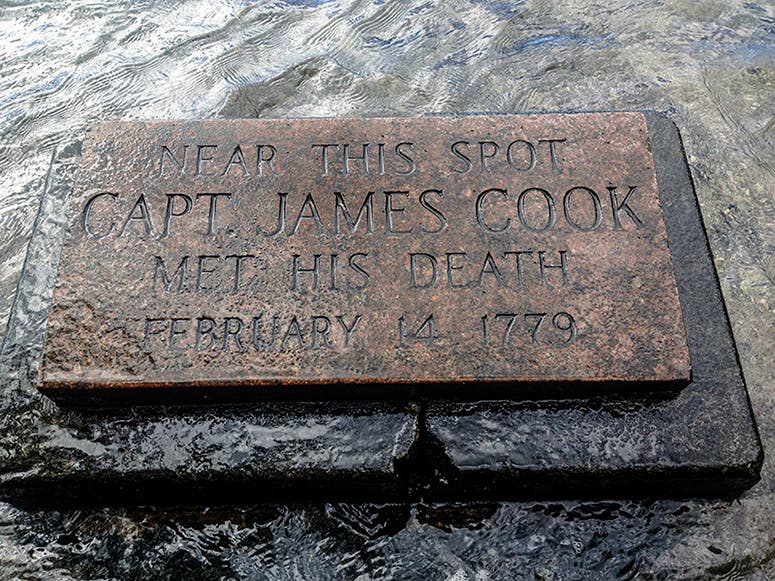

Late in 1777, the ships sailed north and discovered an unexpected set of islands in the middle of the north Pacific, which Cook named the Sandwich Islands, after the First Lord of the Admiralty, the Earl of Sandwich. As best can be determined, this was the first encounter by any European with what we now call the Hawaiian Islands. They stayed only a few days on Kuaui, then sailed north to undertake their mission to search for a northwest passage. They reached Vancouver Island and encountered the totem- and mask-making natives of the surrounding area, collecting some of their elaborate crafts. It soon got too cold to explore further, so the ships returned to Hawaii in early 1779, where they discovered the Big Island that they had missed the first time around. The natives there treated Cook as a god at first, but when the ships tried to leave and were blown back by the weather, things went sour. When one of their boats was stolen, Cook adopted his usual practice of detaining one of the chieftains until the boat was returned, but this time there was a confrontation that escalated, with the crew firing muskets and the natives wielding spears and knives. Cook, standing on the beach, was fatally stabbed, and died on Feb. 14, 1779. It took the crew a while to recover Cook’s body, which had been cut up and carried away, but eventually most of the remains were returned, and he was buried at sea. There was much grieving among the crew at first, but eventually they realized that their beloved commander had gone out on a high note, as a sacrificed God. Immortality was now surely his.

The voyage continued, as the replacement commander took both ships back up north for the summer. They never did find a northwest passage. and returned home to England in August of 1780. The third voyage was not a great scientific success like the first two, because they had no great scientists on board. But it did confirm Cook’s status as perhaps the greatest navigator and naval commander who ever lived.

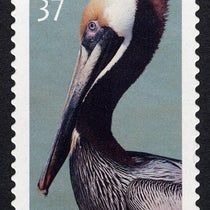

The narrative of the third voyage was published in 1784 as: A Voyage to the Pacific Ocean: Undertaken, by the command of His Majesty, for making discoveries in the Northern Hemisphere ... ; performed under the direction of Captains Cook, Clerke, and Gore, in His Majesty's ships the Resolution and Discovery, in the years 1776, 1777, 1778, 1779, and 1780. Cook wrote the first two volumes, and an editor the third. We have a second edition of this work (1785), which came to us long ago from the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in Boston. Sadly, the atlas didn’t make the trip, so we could not show here any of the engravings of Polynesian and Pacific Northwest coastal cultures, based on the sketches of John Webber, which would have enriched this post.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.