Scientist of the Day - James Bradley

James Bradley, an English astronomer, was born Mar. 23, 1693--or at least, that is the traditional date for his birth, there being no birth record. In the 1720s, Bradley teamed up with a gentleman astronomer, Samuel Molyneux, to attempt to measure the parallax of a star. Stellar parallax was one of the predicted consequences of the Copernican revolution; if the earth moves about the sun in a large circle (186 million miles across), then the stars ought to seem to change position as a result of the earth's motion. If one could measure the angle of parallax of a star, one ought to be able to measure the distance to that star. Two English astronomers claimed to have done just that--Robert Hooke and John Flamsteed--but Bradley was suspicious--their angles of parallax seemed much too large.

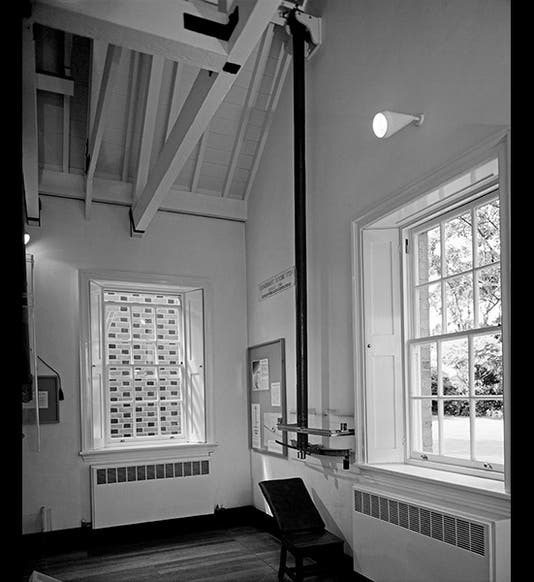

So to make a fresh start, Molyneux bought a zenith telescope from George Graham, a noted instrument maker. A zenith telescope is designed to look straight up, which reduces stresses on the telescope and makes a star easier to track. The telescope was set up in Molyneux’s home at Kew, and was some 24 feet long (tall), which means they had some high ceilings at his family home. Several years later, Bradley would acquire his own zenith telescope from Graham, an instrument only 12 feet long, and this one we can show you, since it later ended up at Greenwich Observatory, where you may see it still (first image). The star they picked to observe was gamma Draconis, because, in London, it is almost directly overhead, just perfect for a zenith instrument.

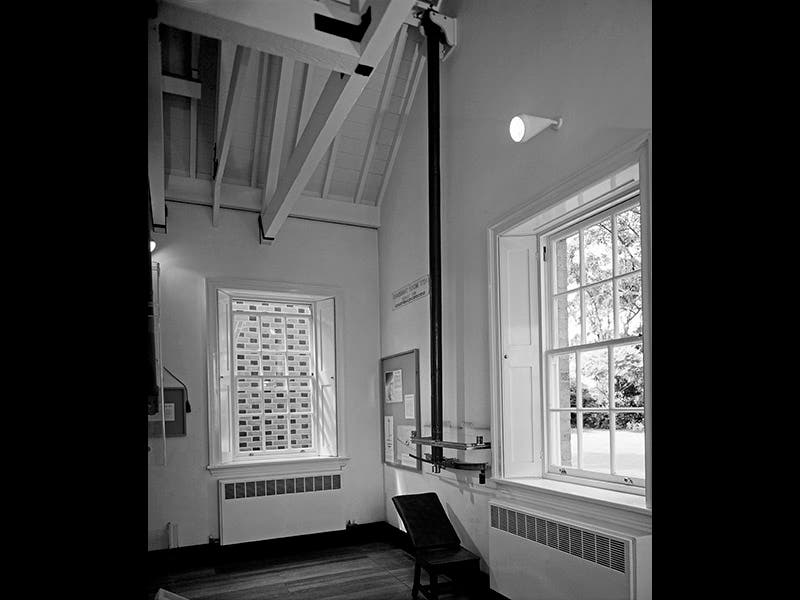

To make a complicated story very short, by 1728 Bradley had indeed detected a slight wobble in the position of gamma Draconis, amounting to some 20" of arc, but the maximum deflection occurred at the wrong time of the year to be parallax. Eventually he figured out that he had detected something called the "aberration of light", an effect caused by the fact that light has a finite speed, and from a moving object like the earth, objects are deflected sideways as the earth crosses the path of the light. Interestingly, the discovery of aberration turned out to be the first experimental confirmation of the Copernican hypothesis, since it is an effect caused by the motion of the earth. The blue plaque (actually green) emplaced in Bradley’s hometown of Redbridge recognizes this accomplishment (second image).

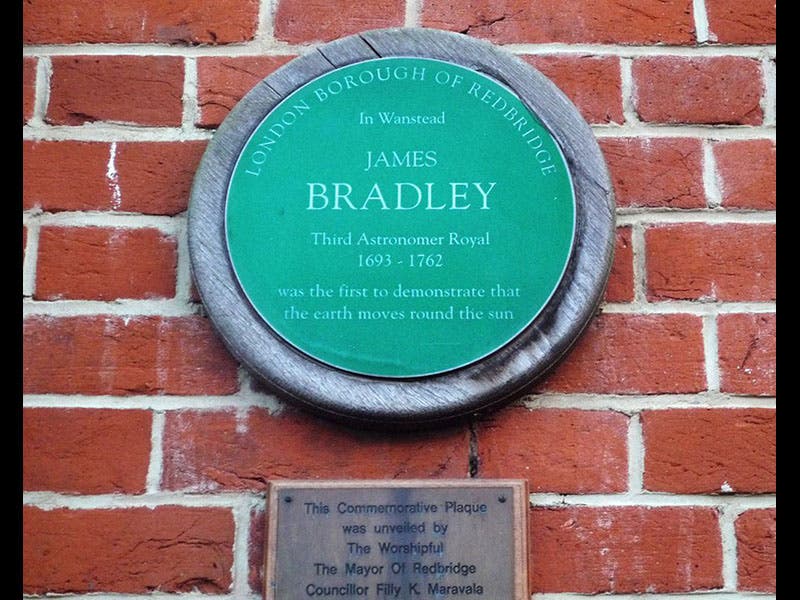

Bradley later became the third Astronomer Royal of England, which is why his telescope ended up at Greenwich. While he was at Greenwich, he established a prime meridian, England's first prime meridian. Many years later, the prime meridian was moved some 20 feet to its present position. But Bradley's meridian is still there (third image), even if no one uses it, and the visitor can clearly see where it used to be.

There is a grand portrait of Bradley in the National Portrait Gallery in London, after an original by Thomas Hudson (fourth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.