Scientist of the Day - James Basire II

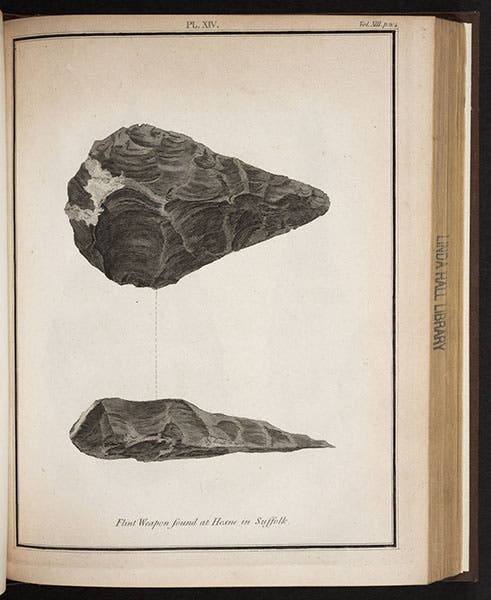

James Basire II, an English engraver, was born Nov. 12, 1769. Basire was the third in a four-deep line of London engravers, the last three of whom were all named James. Oddly, all of the Jameses specialized in scientific engraving, by which we mean engraving images for scientific societies and journals. Equally oddly, all three of them signed their engravings in the same vague way, "Basire sc." or "Js Basire sc." Since James I and James II overlapped for some years around 1800, and James II and James III did the same around 1820, it is not always easy to determine which James was responsible for a particular engraving. Two years ago we profiled the last of the James Basires, James III, and there we had no problem identifying his engraved work, for he was the only James alive at the time. But with James II, it is more difficult. For example, in 1800, John Frere announced the discovery of two prehistoric hand-axes in a pit being dug out for clay, and he published engravings of the two flaked flints in the journal of the London Society of Antiquaries (second image). The engravings are signed "Basire sc." James I was the official engraver for the Society. But so was James II. And they were both alive and weilding their burins in 1800. So we don't now whom to credit.

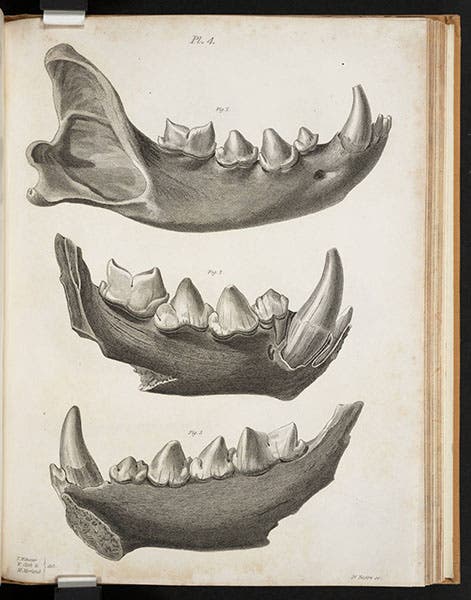

Similarly, in 1821, William Buckland discovered some fossil hyena jawbones in Kirkdale Cave in Yorkshire, and he commissioned drawings and then an engraving to compare a modern hyena jaw at the top with two fossil jaws from the cave. The engraving was published in Buckland's book, Reliquae Diluvianae in 1823, and the engraving is signed Js Basire sc. (third image). We would surmise that this is the work of James II, because of its resemblance to some of the known James II engravings discussed below. But it could be the work of the young James III.

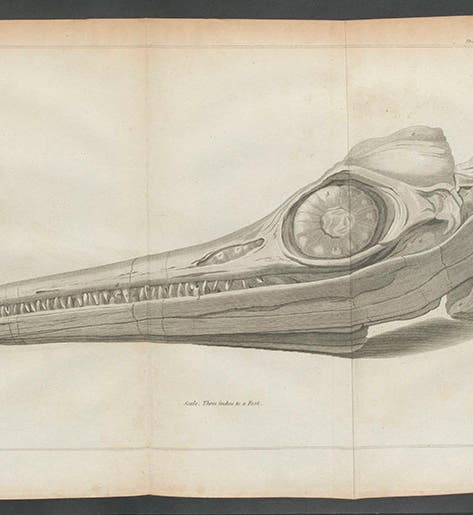

But those are the engravings at the margins. Any engraving signed Js. Basire sc and printed between 1803 and 1818 can be safely attributed to James II. In preparing this piece, I loosely leafed through all the volumes of the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London (Phil Trans for short) for this 15-year period, and it is safe to say that 95% of all the engravings in those volumes were engraved by James II. Many of them are anatomical illustrations, but quite a few are drawings of fossils, for which James II seems to have had a special talent (and which is why we suspect that he engraved Buckland's hyena jaws). As an example, in 1812, Mary Anning unearthed the first ichthyosaurus skull, and it was described and illustrated by Everard Home in the Phil Trans in 1814 (without crediting Anning). The skull was drawn by William Clift and engraved and signed by Basire (first image).

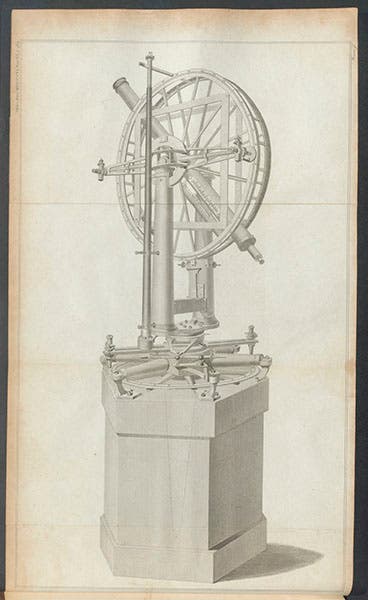

But Basire was quite at home engraving other kind of illustrations. When William Pond wrote an article proclaiming the virtures of a new transit circle built by Edward Troughton, Basire did the engraving (fourth image).

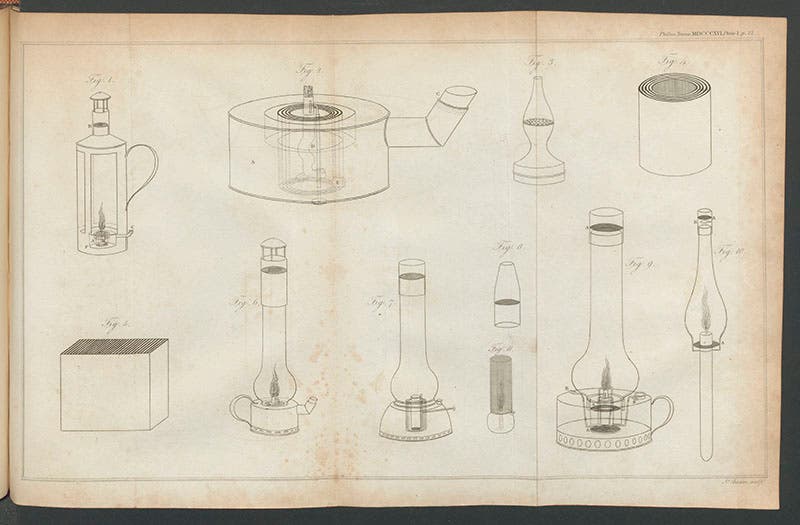

When Humphry Davy in 1816 published a Phil Trans article on his invention of a new kind of safety lamp to protect miners from untimely explosions, Basire did that engraving as well (fifth image).

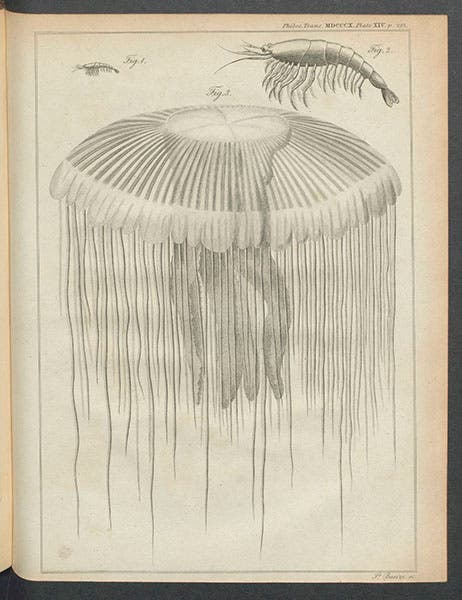

And his engraving of a "medusa pellucens", a jellyfish found by Joseph Banks, was included in an article on luminous animals by J. Macartney, in the Phil Trans for 1810 (sixth image).

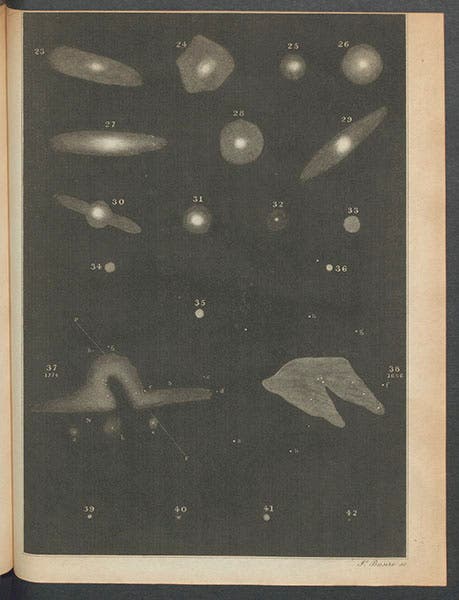

James II's virtuosity as an engraver is most apparent in an illustration he did in 1811 for an article on nebulae by William Herschel, where he exchanged his usual black-on-white engraving method for a white-on-black syyle needed to portray the night sky. From this engraving, we pulled a detail of the signature, so you can see how James II, as well as James I and III, signed their artwork.

Such was the lot of engravers in Georgian and Victorian England that their efforts were seldom if ever praised in the articles that relied on their handiwork. I have looked for many years for some mention of any of the Basires in the various papers in the Phil Trans that contain Basire engravings, and I have yet to fit a single example of an appreciative word. I like to think that a tribute is out there somewhere, but I am not very hopeful.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.