Scientist of the Day - Jacques-Louis David

Jacques-Louis David, a French painter, was born Aug. 30, 1748. David was a master of the style known as Neoclassicism, which, with its flat polished surfaces, frozen figures, and high intellectual content, does not appeal so much to modern tastes. But in late 18th-century France, David was regarded as the finest painter since Michelangelo. WE include him in our Scientist-of-the-Day series because David twice portrayed historical scenes involving physicians or natural philosophers, and twice painted portraits of living scientists, or would-be scientists. Let us look at this scientific legacy in oil.

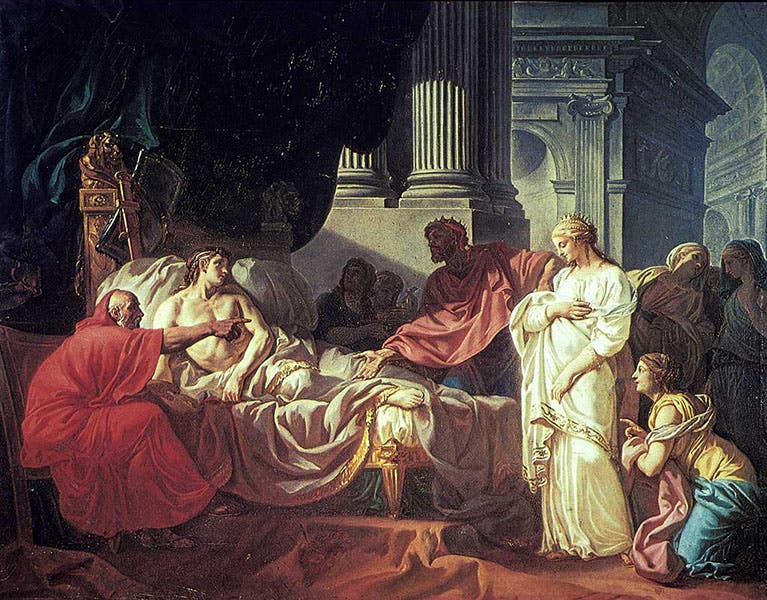

We begin with one of David’s early paintings, Antiochus and Stratonica, painted in 1774 (second image, above). It depicts Erasistratus, a Greek physician and one of the founders of the anatomical school of Alexandria, diagnosing the illness of Antiochus, the son of the Emperor Seleucus, who took over most of Alexander the Great's kingdom after his death. Antiochus was passionately in love with his young mother-in-law, Stratonica, but he was determined not to reveal his feelings and was slowly dying of misery. Erasistratus was called in and could find no physical ailment, and he wondered if the illness had emotional or mental roots. Noting that Antiochus flushed with color whenever Stratonica came into the room, he guessed the cause, and told Seleucus. Far from minding, Seleucus gave up his young wife to his son and even gave him part of his kingdom. Erasistratus was not only rewarded financially, but he became one of the first physicians on record to connect a physical illness to a psychological cause. The story, set in 294 B.C.E., is told by many ancient sources, including Pliny and Plutarch, but sometimes with other physicians in the role of Erasistratus, so we cannot really take the story as fact. But it makes for a dramatic painting. That is Erasistratus in red, pointing at the glowing Stratonica, with Seleucus in between, rather amazed at the diagnosis.

Another famous David painting is a portrait of Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier and his wife, Marie-Anne Pierrette Paulze, Madame Lavoisier (third image, above). At the time of this painting, 1788, Lavoisier had discovered the oxygen theory of combustion, was reforming chemical nomenclature, and was providing chemists with a much-expanded list of basic elements, all of which would be codified and explained in his book, Traité élémentaire de chimie, published in 1789. Marie-Anne was more than a wife, she was Antoine's companion in the laboratory. David's painting is not only the sole portrait we have of Lavoisier made during his lifetime, but one of the few joint portraits of any husband-and-wife scientific team before the modern age. It reminds me of the many fine double photographic portraits we have of William and Elizebeth Friedman, whom we celebrated just a few days ago. David's portrait of the Lavoisiers is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Our third David painting with a scientific theme is perhaps his most famous, The Death of Socrates, painted in 1787, the year before the Lavoisiers’ portrait (fourth image, above). Socrates was the teacher of Plato, and the teacher-once-removed of Aristotle, which made him the progenitor supreme of Greek scientific thought. The painting depicts Socrates choosing death over exile and preparing to drink his hemlock, while all of his students despair, except Plato, at the foot of the bed, who understands. Coming on the eve of the French Revolution, the painting makes a strong statement about duty, personal strength, and the importance of resisting injustice, even at the cost of one's life. The inclusion of Plato, who was in fact not present at the death of Socrates, was a justifiable bit of artistic license, since Plato's Phaedo is our source for the circumstances of Socrates' death.

Thomas Jefferson was present at the unveiling of The Death of Socrates and was so impressed that he called it to the attention of his young artist friend, John Trumbull, then in London. Trumbull was preparing the small version of his Declaration of Independence, the larger version of which is now in the U.S Capitol Rotunda. You can see quite a bit of David’s style in Trumbull's painting. The Death of Socrates was commissioned by a patron, and even Napoleon couldn't pry it away when he wanted to buy it for the national collection. But in 1931, the heirs did agree to sell, and it was acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, where you can see it today.

Finally, we thought we would include David’s dramatic portrait of Napoleon Crossing the Alps (1802), the version at the Palace of Versailles (fifth image, above). Napoleon thought he was, or could be, a scientist, and he did organize the scientific expedition to Egypt in 1798, many facets of which have been discussed in these posts. David was invited to go along as official expedition artist, but he declined, so Dominique-Vivant Denon went in his stead.

Several portraits and self-portraits of David survive, but we chose for today’s post a portrait by Rembrandt Peale (first image), who was trained by one of the important scientific figures of the early American Republic, his father, Charles Willson Peale. The asymmetry of David's face was reportedly the result of a fencing wound suffered in his youth, which caused his mouth to droop and made speaking difficult. It must have been a great hindrance to David in socially-conscious Paris, especially during the reign of Napoleon. Peale's portrait of David is in the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia. Interestingly, Rembrandt Peale also painted a fine portrait of David’s stand-in in Egypt, Vivant Denon.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.