Scientist of the Day - Jacob Hoefnagel

Jacob Hoefnagel, a Flemish painter, engraver, and miniaturist, was born around 1573 in Antwerp and died sometime after 1630. Jacob was the son of Joris Hoefnagel, also a miniaturist and painter of naturalia, whom we profiled only last week. Jacob was born just before his family fled Antwerp in the aftermath of the sack of that city by the Spanish, and he spent most of his life in the major cities of the Holy Roman Empire, including Frankfurt, Vienna, Munich, and Prague. He learned how to draw from his father, and from a brief apprenticeship back in Antwerp. Like his father, who died in 1600 or 1601, he found a patron in Emperor Rudolf II, serving him about the same time that Johannes Kepler was Rudolf’s Imperial Mathematician, although it is not known if the two interacted in any significant way. Like Kepler, Jacob had a hard time getting the court exchequer to pay his salary, so he was frequently in financial difficulty. Somehow, he found the opportunity to marry five times.

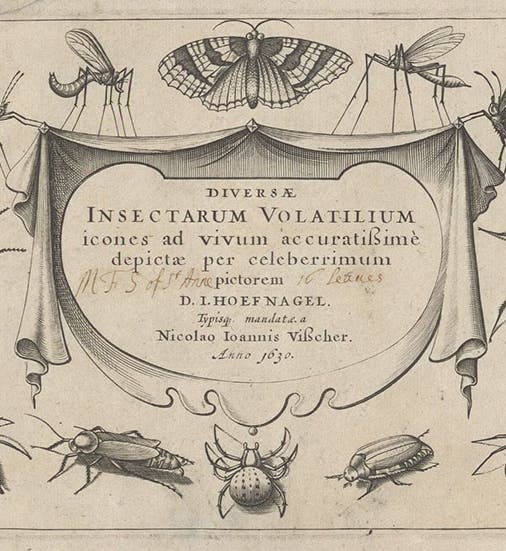

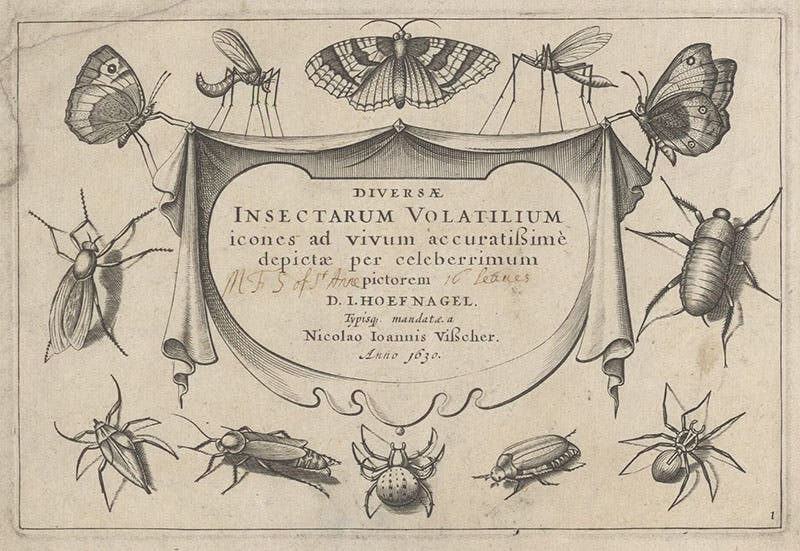

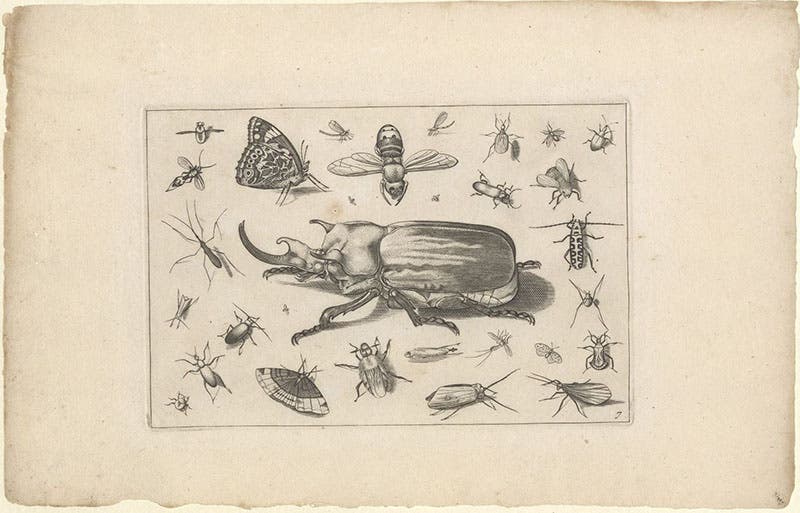

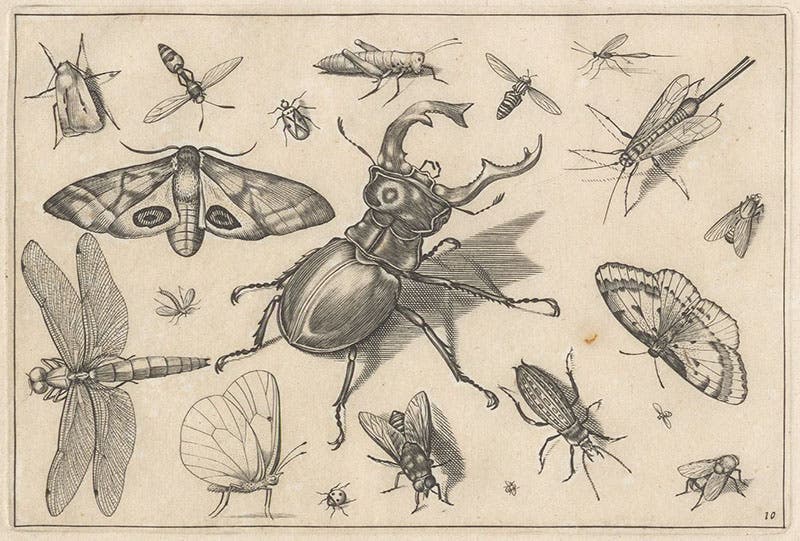

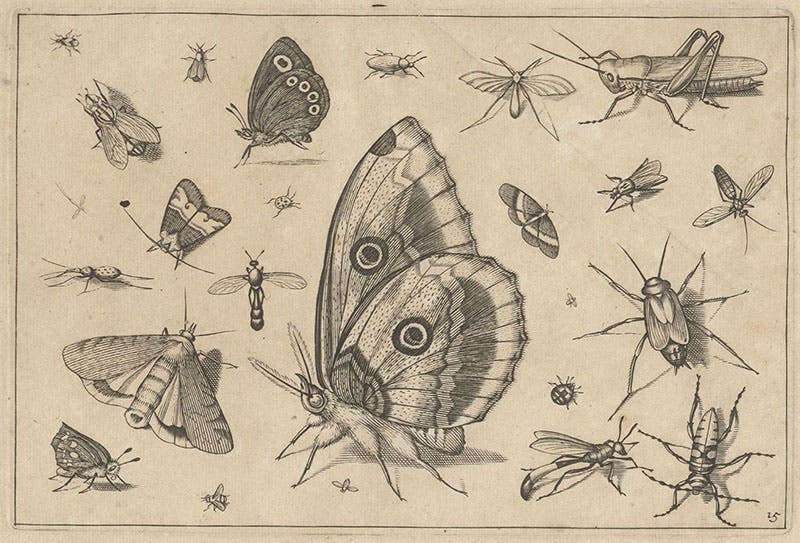

His first significant art production was the Archetypa studiaque patris Georgii Hoefnagelii, (1592), a collection of 48 prints of natural history objects, which he engraved after drawings by his father. Jacob was only 19 years old at the time. We do not have this work, but the engravings are typical of many natural history prints of the time, depicting arrangements of naturalia that might include small animals, insects, fruit, and flowers, artfully displayed, and usually with some proverb or emblematic motto in evidence. Engraving the Archetypa provided Jacob the experience and background he needed for producing a book that we do have in our collections, his Diversae insectarum volatilium icones ad vivum accuratissime depictae (Images of a variety of flying insects, very accurately drawn from life, 1630).

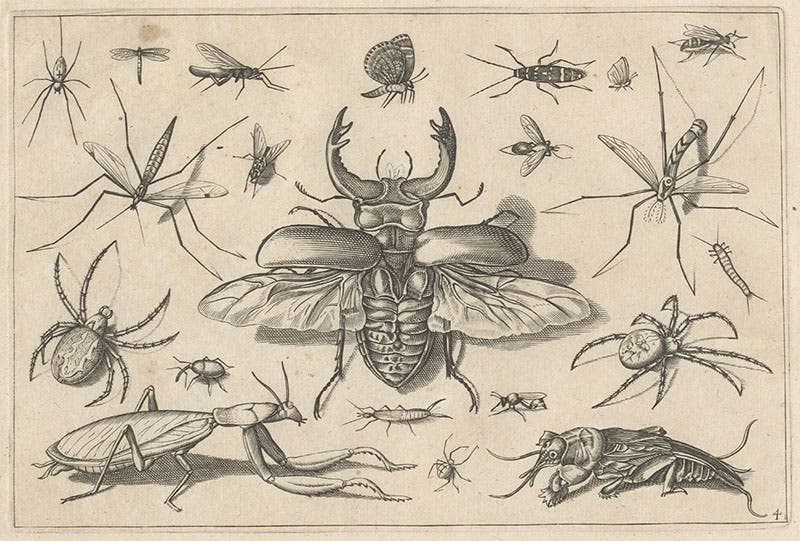

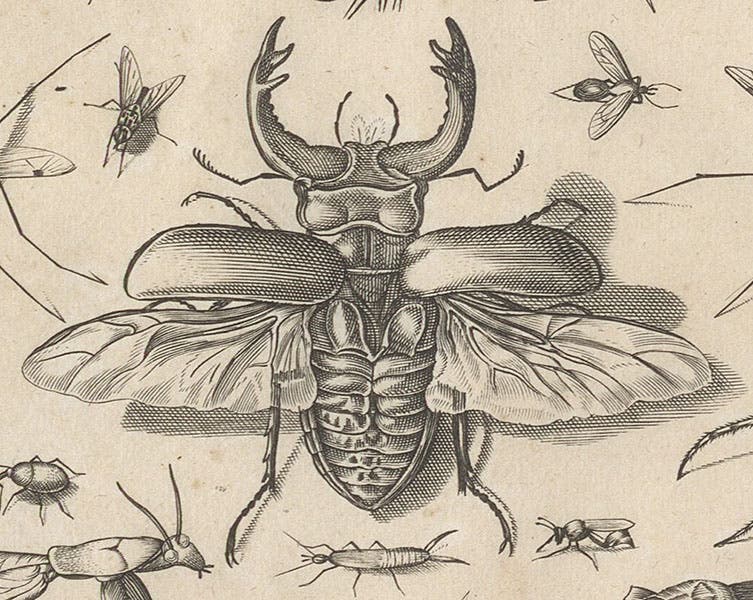

Our copy consists of all 16 prints, unbound and matted, and stored in a box. All of our images today are from this set, which we have removed from the mattes, since they are not contemporary. These prints resemble at first glance the prints in the Archetypa, but they lack the emblematic apparatus, and although the Diversae prints are also carefully arranged, they depict only insects. It is not the first book devoted solely to insects – Ulisse Aldrovandi had published his De animalibus insectis in 1602 – and Hoefnagel did not attempt to be comprehensive, which Aldrovandi did. But there is no comparison when it comes to the illustrations, as you can determine for yourself. Aldrovandi used crude woodcuts that were often inaccurate to illustrate his book, and employed no magnifying aid as far as we can tell, while Hoefnagel’s engravings are stunningly realistic and suggest that a lens was used.

Did Hoefnagel use a microscope? Interestingly, a useable microscope had been constructed about 1619 by Cornelius Drebbel, and we know that Constantijn Huygens, a Dutch diplomat and future father of Christiaan Huygens, acquired a Drebbel microscope in 1622 and extoled its virtues. It just so happens that Constantijn married the niece of Joris Hoefnagel, which made him and Jacob cousins of a sort, and they must have known each other. So it is not impossible that Jacob saw Constantijn’s Drebbel microscope and perhaps used it. But there is no documentary evidence for this. So for now, Francesco Stelluti keeps the credit for publishing the first image of an insect as viewed through a microscope, which he did when he issued a broadsheet in 1625 depicting three magnified bees.

There is no portrait of Jacob Hoefnagel that I know of – shame on Joris for not painting his son when he had the chance. Nor do we know when Jacob died – he just disappears from the historical record after 1630. We are grateful that he left his collection of insect engravings behind as a memorial.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.