Scientist of the Day - Jacob Epstein

Jacob Epstein, an American-born British sculptor, was born Nov. 10, 1880. Epstein was one of the most controversial pioneers of modern sculpture. From his very first work, The Ages of Man for the new British Medical Association building in London, executed in 1907-08, he flouted the western sculptural canons, drawing upon Indian rather than Greek ideals, and creating nude human forms that were unmistakably erotic. The 18 nudes survive only in severely mutilated form (and the building is now, interestingly, the Zimbabwe Embassy) (second image, below). I do not know when and by whom the forms were mutilated.

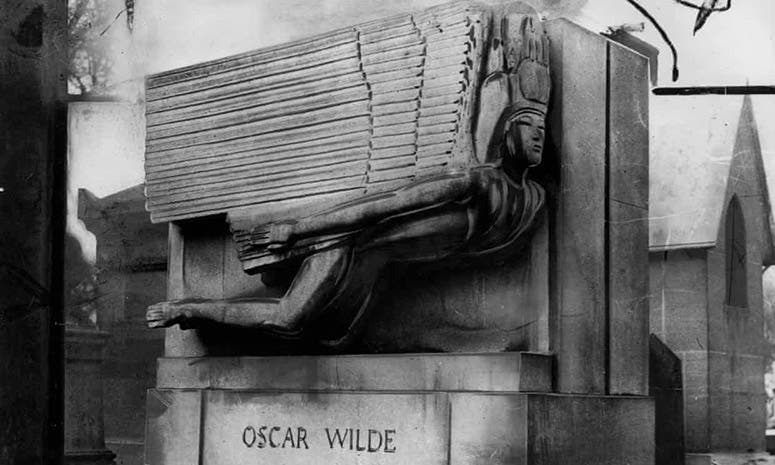

Epstein’s next piece, a memorial for Oscar Wilde for the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris and finished by 1912, was even more controversial (third image, below). It depicted a winged figure, carved from a twenty-ton block of Derby limestone, which bears a resemblance to Assyrian carvings that Epstein admired in the British Museum. However, the figure was nude and undeniably male, and the sight of a male organ was apparently so offensive that the memorial was kept covered by a tarp for two years before solutions were devised. Poor Paris – first Epstein’s Wilde, and then Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring the next year! It is amazing that the city survived the scandals. We show a 1960s photo of the memorial, because the stone is now kept behind a shield in an unsuccessful attempt to prevent Wilde admirers from leaving lipstick-smeared kisses on the sculpture.

Sometimes Epstein showed his scorn for convention in other ways, as with his Rock Drill of 1914, an attempt to portray the dehumanizing effect of western industrial society by giving human form to a pneumatic drill. It was later dismantled by Epstein and only one grainy photo survives, which you can see here. According to the National Portrait Gallery, this was considered a Vorticist work, a movement briefly flirted with by Epstein, and a movement that we discussed not two weeks ago, in an entry on Edward Wadsworth.

Bronze busts of Albert Einstein, at The Tate (left) and the Science Museum, London (right), sculpted by Jacob Epstein, 1933, casting dates unknown (tate.org.uk and sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk)

Epstein's career went on like this, outraging many, delighting some (such as Henry Moore), when, out of the blue, in 1933, Epstein met Albert Einstein at a camp at Cromer, near Norfolk. Einstein had fled Germany and was in seclusion there, awaiting a move to the United States. According to one of Einstein's biographers, Ronald Clark, Epstein remarked of Einstein: "His glance contained a mixture of the humane, the humorous and the profound. This was a combination which delighted me." Einstein sat for Epstein, and the result was a portrait bust, rough and chiseled like others of Epstein’s portraits (including his own self-portrait, first image). Nevertheless, it captured an Einstein that was indeed humane, humorous, and profound. Ten casts were made of the original artwork, and they can be seen in such places as the National Gallery of Scotland, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, the Tate, the Science Museum in London, and the Hirschhorn in Washington, D.C. We show the examples in the Science Museum and the Tate, both beautifully photographed (fourth and fifth images, just above).

Bronze bust of Albert Einstein, sculpted by Jacob Epstein, 1933, rare book reading room, Linda Hall Library (photo by author)

In 1964, one of the original casts was sold at Sotheby's, and it was purchased by the Linda Hall Library. It may be seen today in the outer reading room of the History of Science Collection. We have a splendid collection of busts of scientists, but they have not been professionally photographed, so I offer an amateur view, taken with my iPhone (sixth image). Even with the flat lighting, Einstein still manages to look humane and cheerful. In years past, when the outer reading room was overseen by Nancy Officer, Albert often sported a tam, a watch cap, or a scarf, depending on the mood of his caretaker. Now, he pretty much faces the world unadorned and unprotected, much like the rest of us. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.