Scientist of the Day - Jacob Bontius

Jacob Bontius, a Dutch physician and naturalist, died Nov. 30, 1631 at age 38 or 39. Bontius was one of the first European physicians to go to the East Indies and write about the diseases, animals, and plants of the area. He wrote a book on medicine in the Indies, De medicina Indorum, that was not published until 11 years after his death, in 1642. Wikipedia describes this as a four-volume work, but in fact it is a small one-volume duodecimo of only 212 pages. We do not have a copy, but there is one not far away, at the Clendening Library at the KU School of Medicine in Kansas City. It has a charming engraved title page.

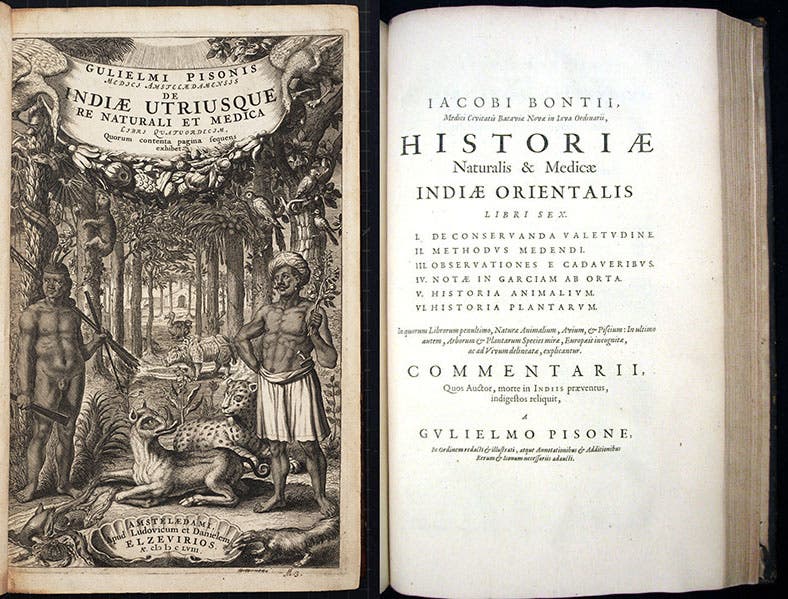

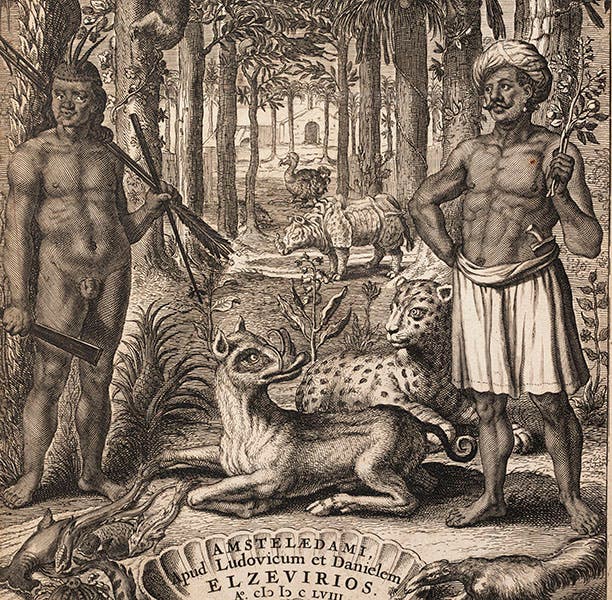

Bontius also wrote a work called Historiae naturalis et medicae Indiae orientalis (On the natural history and medicine of the East Indies), which is often cited with the date 1631, as if it were published that year. As far as I can determine, the book was not published until Willem Piso included it in the second edition of his Historiae naturalis Brasiliae (Natura History of Brazil, 1648), which he retitled, with a nod to Bontius, De Indiae utriusque (On the Two Indies) and printed in 1658. We have both of Piso's editions in our Library. We show here the engraved title page of the 1658 edition that includes Bontius's natural history, and the half title page within that introduces Bontius's treatise (second image).

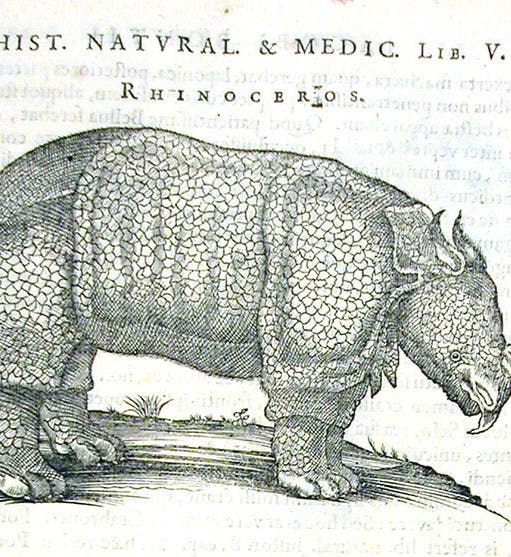

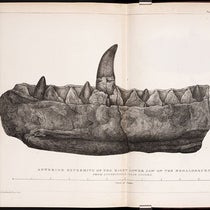

A number of the illustrations in Bontius's Natural History are notable. He shows a rhinoceros, one of the very few rhino images in the entire century that is not a copy of Albrecht Dürer's rhino, and it turns out that Bontius's woodcut is the very first printed image in the West of the one-horned Javan rhinoceros (first image).

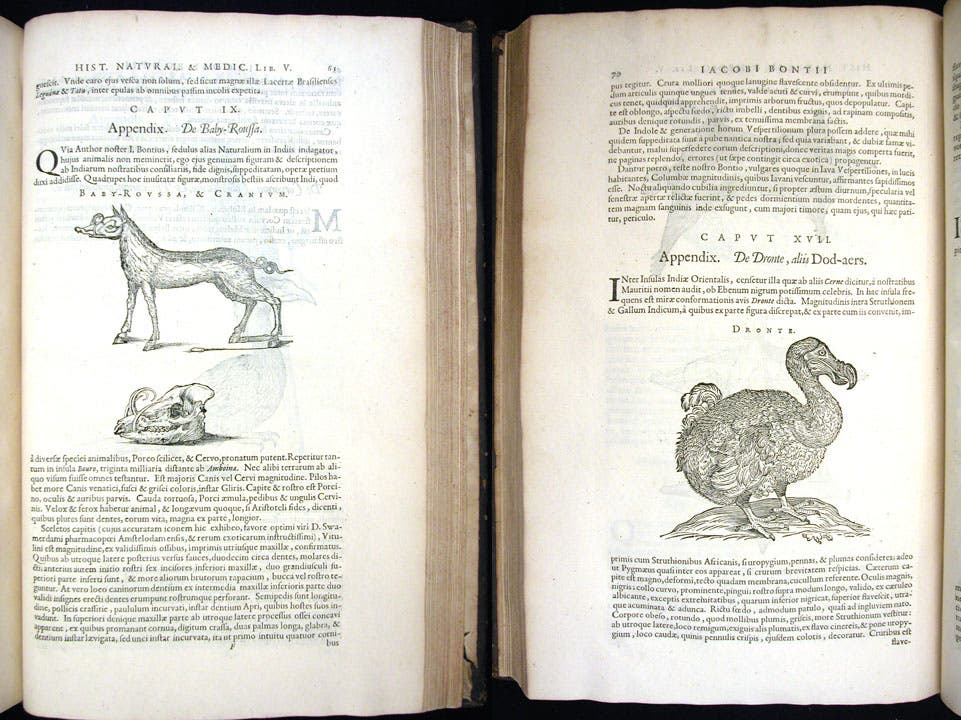

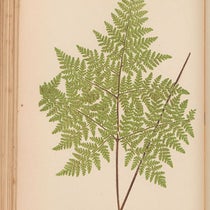

Bontius also discusses and has an image of a babirusa, the distinctive tusked pig of Sulawesi, and a tiger, which he probably saw in Bali. His dodo is a particularly good representation of a bird that was usually badly caricatured in print (third image).

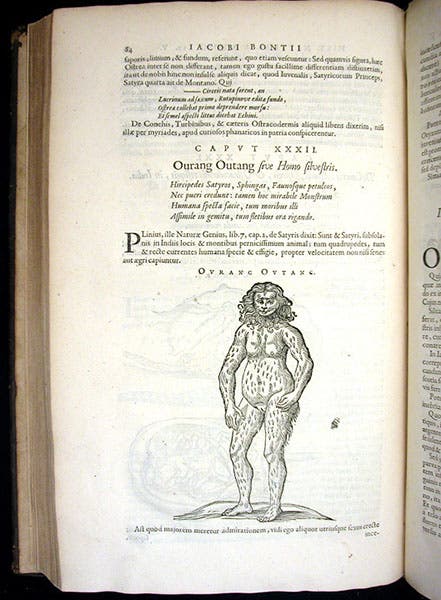

Certainly the most intriguing illustration has to be that of an orangutan. Bontius heard accounts from Borneo natives of these tailless manlike apes and passed along a description, as well as the name (Orangutan is Malay for “man of the woods”). It is not clear where the image came from, or indeed where any of Bontius's images came from; we don't know if Piso commissioned them, or if any were part of the Bontius manuscript he was using. The only image that we have a prehistory of is that of the Javan rhinoceros, which we know was drawn by the Dutch painter Philips Angel; the watercolor is a dead ringer for the woodcut, and the watercolor still survives. But we do not know if Bontius saw it or commissioned it, or whether Piso came across it back in the Netherlands – probably the latter.

One of the interesting features of the two editions of Piso's Natural History is that the same copper-plate engraving was used for the engraved title page of both, but it was reworked for the 1658 edition to indicate that the book now discusses the East Indies as well as the West. If we look at the center area of the 1648 title page, we see only a river god in the front and some dancing natives in the far distance. In the 1658 engraving (fifth image), the babirusa has replaced the river god, and behind him is a tiger (looking more like a leopard), a rhinoceros (but Dürer's, not the Javan), and the dodo, all animals discussed in Bontius's section of the book.

Bontius never made it back from the Dutch East Indies, and we have no portrait. We are fortunate to have the two posthumous editions of his books as his legacy.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.