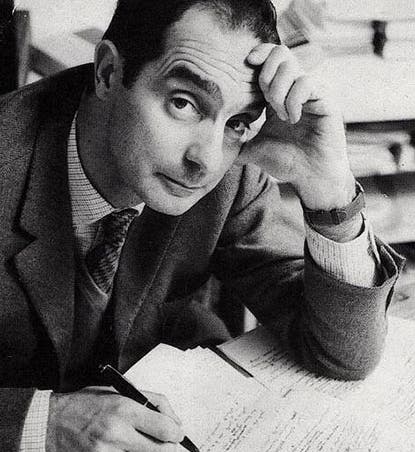

Scientist of the Day - Italo Calvino

Italo Calvino, an Italian writer, was born Oct. 15, 1923, in Havana, Cuba (hence his first name, a reminder of his origins by his Italian parents, which turned out to be not so appropriate when they all moved back to Italy). Like his parents, Calvino was politically active, a communist in fascist Italy, and an active member of the anti-fascist resistance in the last years of World War II. He was a writer from his earliest days, earning a living as a journalist and editor, and writing realist novels that didn’t please him or his audience. He soon invented his own style, a blend of science fiction, fantasy, and surrealism. In my opinion, his finest work came in the form of short stories, in particular those in his book Cosmicomics, published in Italian in 1965 and in English translation in 1968. When I first encountered this book, I found its scientific inventiveness immensely appealing, and I still do, forty years later.

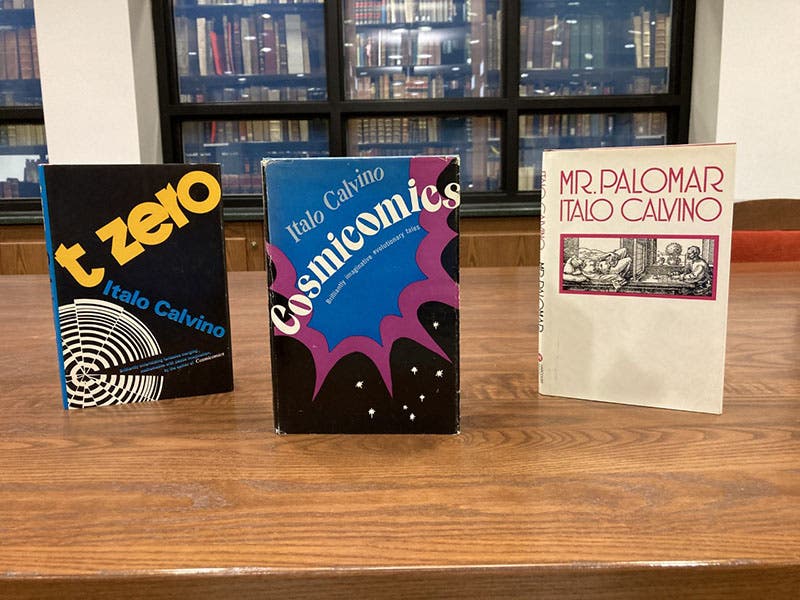

First English editions of t zero (1969), Cosmicomics (1968), and Mr. Palomar (1985), all by Italo Calvino, author’s copies (photo by the author)

The book is hard to describe. It consists of 12 stories, unrelated plot-wise, but very much fitting under the same skewed rubric. Each story is prefaced with a brief paragraph stating a cosmological fact, such as the one that opens the first story: “At one time, according to Sir George H. Darwin, the Moon was very close to the Earth. Then the tides gradually pushed her far away; the tides that the Moon herself causes in the Earth’s waters, where the Earth slowly loses energy.” Immediately thereafter, the narrator jumps in: How well I know! – old Qfwfq cried, - the rest of you can’t remember, but I can. Qfwfq – the narrator in all the stories – then proceeds to tell us what life was like when the Moon at her closest hung ten feet away, and they would go out in rowboats with ladders and climb to the Moon and back, and how traumatic it was when it became apparent that the Moon was receding.

Another story begins with a (now discarded) conclusion from the Steady State theory of Fred Hoyle and others that, as the universe expands, new matter, in the form of hydrogen atoms, must be continuously created at the rate of one atom every 40 cubic centimeters every 250 million years. Qfwfg begins: I was only a child, but I was aware of it – I was acquainted with all the hydrogen atoms, one by one, and when a new atom of hydrogen cropped up, I noticed it right away. The kids played with them, because they were the only things in the universe to play with, and made up elaborate marble games for themselves. But his friend Pfwfp cheated; he would sneak out at night and find new atoms, and then rub and scuff them so they looked like old atoms, so Qfwfq would not realize that he was secretly building up his playing stock.

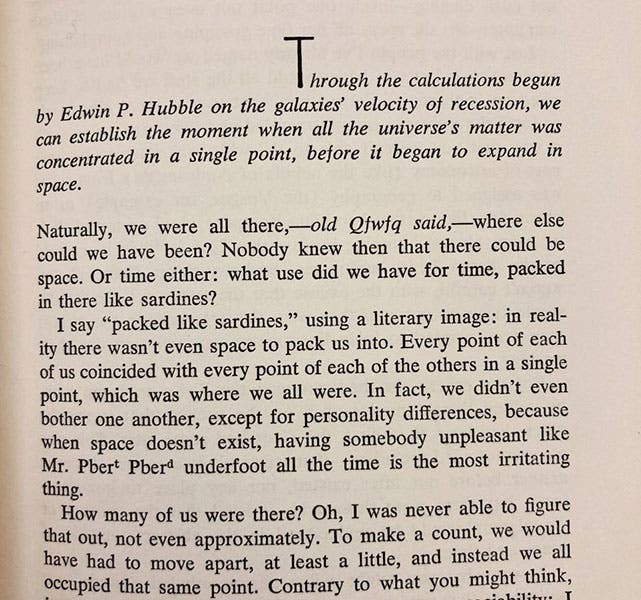

My favorite story in Cosmicomics – I think everyone’s favorite story – is the third one, called “All in One Point,” spun off from the fact that, in the Big Bang theory that follows from Edwin Hubble’s discovery of the expansion of the universe, at one time all the matter in the universe was concentrated in a single point. Qfwfq’s opener is wonderful: Naturally we were all there – where else could we have been? Nobody knew then that there could be space. Or time either: what use did we have for time, packed in there like sardines? And it just gets wackier and more clever. I took a photo of the first half-page of the story, so you can read another paragraph if you want; for more, you will just have to find the book (third image). I encourage you to do so.

First page of “All at One Point,” a short story by Italo Calvino, in Cosmicomics, 1968 (photo by the author)

Calvino wrote a follow-up collection of Qfwfq tales, called t zero, which I didn’t find nearly as compelling as Cosmicomics. He also wrote a novel, Mr. Palomar, the main character of which is named after the famous telescope in southern California. However, this is not a novel about astronomy – it is about “seeing,” about a man who is obsessed with looking, and with the idea and methods of looking, at the world outside, and within. I enjoyed it as well. It was published in English in 1985, right after Calvino had a sudden stroke and died, age 61. So the reviews of the book are a combination of review and eulogy, mixed with a realization that perhaps the greatest Italian writer of that generation was gone, before he could reap the Noble Prize that he surely deserved.

For some reason, when I think of Calvino, I think of Jorge Luis Borges, whom we wrote about this past summer. I am not sure why – no one would ever confuse a Calvino story with a piece by Borges. I suppose they fit in the same frame because both were fascinated by science but used it mainly as a launching point for inventive excursions on the limitations, and possibilities, of being a human being. The world needs more writers like them.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.