Scientist of the Day - Iridium 33

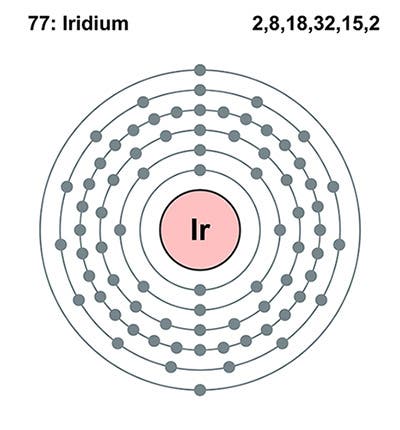

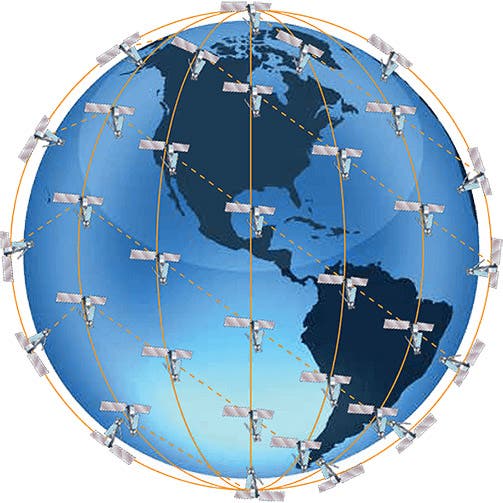

Iridium Satellite LLC was a private firm that began, around 1987, to plan a network of satellites to support portable satellite phones, allowing for world-wide coverage. They acquired financial backing from Motorola, who also provided the CPUs for the satellites. The original plan was to have 77 satellites in 7 polar orbits, and hence the name “Iridium,” since the iridium atom has 77 electrons whirling around in their orbits looking very much like an Earth with 77 satellites (second image). Most of the satellites were launched from the United States, with each launch putting multiple satellites into orbit, but some were consigned to Russian or Chinese rockets. The first launch was on May 5, 1997, and just over a year later, nearly all of the satellites were in place. There were 15 launches in all for what turned out be 72 satellites (66 + 6 spares), and the launch success rate was 100%, which is quite amazing. The entire network is sometimes referred to as the Iridium Constellation (third image). When it was decided to change the number from 77 to 66, they chose to keep the Iridium name, and one can understand why, since element 66 is called dysprosium, and not only has no one ever heard of dysprosium, but it sounds suspiciously like dysfunctional, which is not too attractive to investors. The element iridium, by the way, was discovered in 1803 by one of our previous honorees, Smithson Tennant.

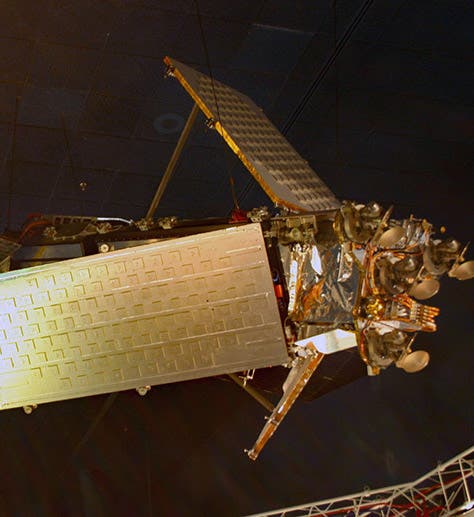

Each satellite was identified by a number. Iridium 33 was launched from Kazakhstan by a Russian Proton rocket on Sep. 14, 1997, along with six fellow Iridium satellites. It whizzed uneventfully around in its orbit, some 485 miles up, while the company back on Earth went bankrupt, was reorganized, and fitfully carried on. The problem with a satellite phone network is that all of the satellites have to be in place for the network to function, which requires a lot of up-front costs, on the order of hundreds of billions of dollars. Plus, it turned out that the market for satellite phones had been drastically over-estimated.

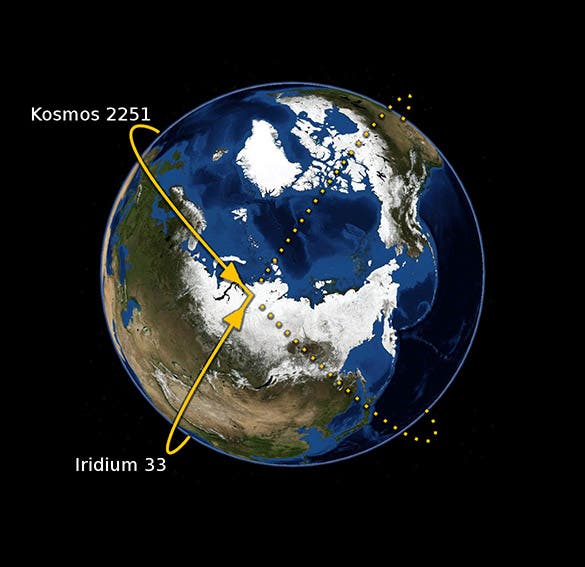

But Iridium 33 was immune to all the financial consternation down there on the surface, speeding around the Earth at 17,000 mph for 11½ uneventful years, until it finally met its maker, or, more accurately, it met the handiwork of somebody else’s maker. On this day, Feb. 10, in 2009, Iridium 33 collided with Kosmos 2251, a defunct Russian spacecraft, in a collision dwarfing all other vehicular collisions. Iridium 33 hit Kosmos 2251 broadside; the mutual impact speed was over 22,000 mph. It was the first collision ever between two intact spacecraft. Debris, in the form of nearly 2000 fragments, rapidly spread out along the orbits of the two spacecraft (fifth image).

The fragmentation of Iridium 33 and Kosmos 2251 called renewed attention to the growing problem of space debris or space junk in low Earth orbit. There are now tens of thousands of pieces of old spacecraft, launch boosters, and debris in low orbit, and they are a hazard to active spacecraft; the International Space Station, every year or so, has to move out of the way of a known fragment headed right at it. Even more problematic is the possibility that the proliferation of space debris might cascade out of control. A NASA engineer named Donald J. Kessler in 1978 pointed out that, as space junk accumulates, there comes a point when collisions create more debris, which cause more collisions, and the whole thing proliferates uncontrollably. This scenario is now called the Kessler Syndome, and it is a state to be avoided if we wish to continue in space, or out into deep space. It has even been suggested that the Kessler Syndrome provides an explanation of the Fermi paradox, which we discussed obliquely in our post on the fictional John Murdoch – if extraterrestrials exist, where are they? There is a real possibility that technological civilizations might end up with so much clutter in orbit around their planets that they cannot navigate through it all, and are effectively shut out of space, discovering too late that littering is bad for everyone, including would-be spacegoers.

Iridium 33 was replaced with one of the spares in orbit, and the entire constellation of satellites still functions under the aegis of Iridium Communications. However, all of the original satellites have now been replaced with next-generation models. I hope the outmoded satellites were de-orbited and did not contribute 66 more items to the ever-expanding space junk catalogue.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.