Scientist of the Day - Immanuel Kant

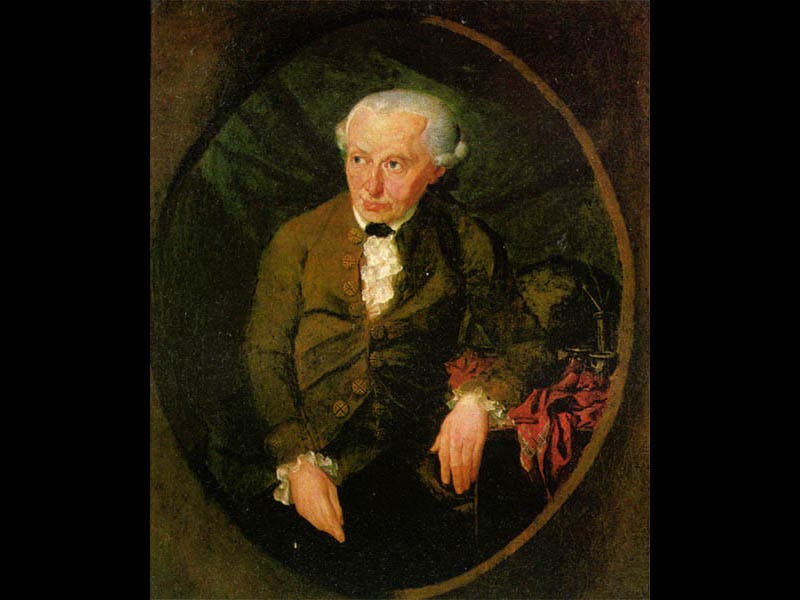

Immanuel Kant, a German philosopher, was born Apr. 22, 1724. Nearly every short biography of Kant includes a quotation from the end of the Critique of Practical Reason (1788), where Kant says: “Two things fill the mind with ever new and increasing admiration and awe…: the starry heaven above me and the moral law within me." That is indeed a handsome phrase, and one can see why biographers are much taken with it. However, such biographies almost always go immediately on to discuss Kant as moral philosopher and pass right over the first part of Kant's dicta, that the heavens and its laws are worthy of our admiration. Kant did more than just admire the heavens--he made several notable contributions to astronomy and cosmology before he descended the slippery slope into philosophy. In the 1750s, Kant read a review in a German journal of a book by Thomas Wright, An Original Theory or New Hypothesis of the Universe (1750). The reviewer said that Wright claimed that the Milky Way was a clue to the distribution of stars in space, but the reviewer did not explain what that distribution was (the second image above, showing a cross-section of the Milky Way, is from Wright’s book, but Kant never saw it). Kant read this and immediately concluded that if we see a band of stars across the heavens, it must be because our star system is shaped like a broad thin disk, with the sun at the center. In a word, Kant proposed not only the existence of our Galaxy, but its proper shape. He announced his conclusion in Allgemeine Naturgeschichte und Theorie des Himmels (A Universal Natural History and Theory of the Heavens, 1755).

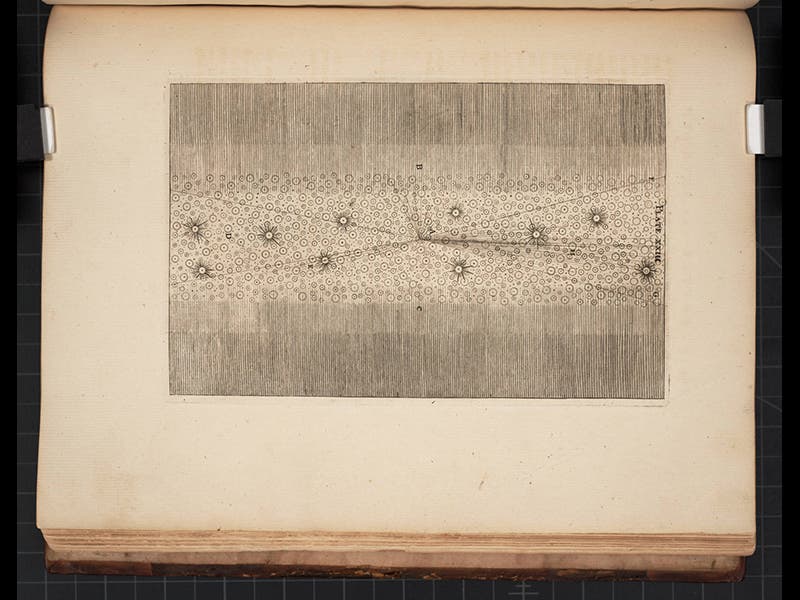

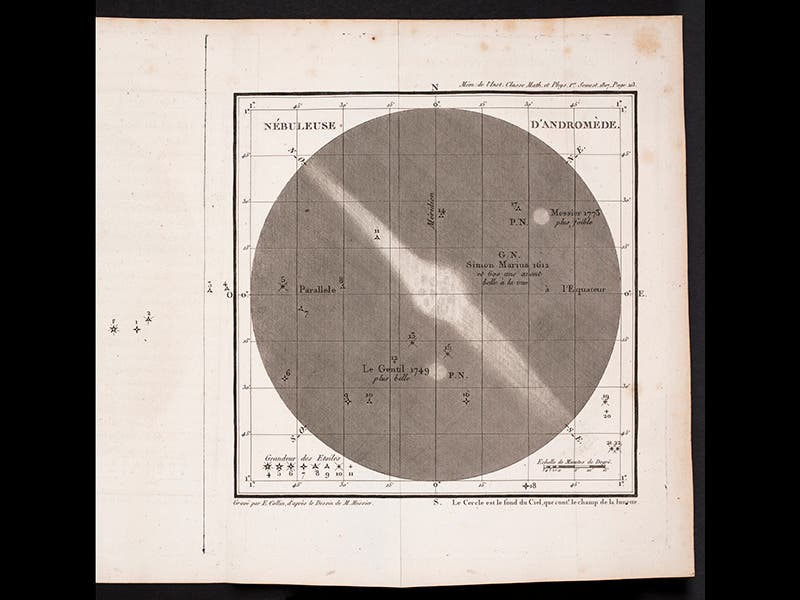

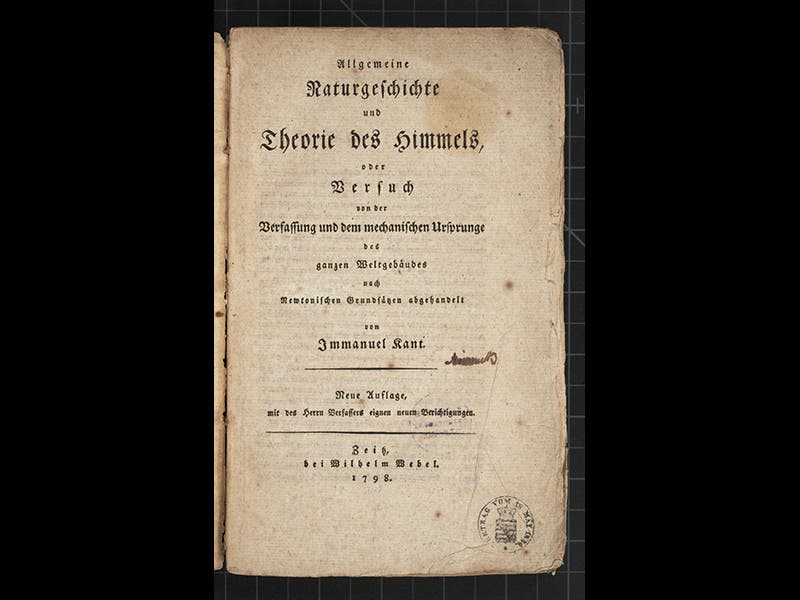

In this book, Kant also suggested that some of the lens-shaped nebulae in the sky, such as the nebula in Andromeda (third image above) might be galaxies of stars just like our Milky Way Galaxy. However, Kant's innovative ideas went unnoticed for a long time. His publisher went bankrupt just as the book was printed; copies were confiscated by the courts and most of them disappeared. Even later printings are very scarce. We have in the History of Science Collection a copy of the second edition (1798), and we are very pleased to have it (fourth image above). We displayed it in our 2010 exhibition, Thinking outside the Sphere.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City