Scientist of the Day - Ian Malcolm

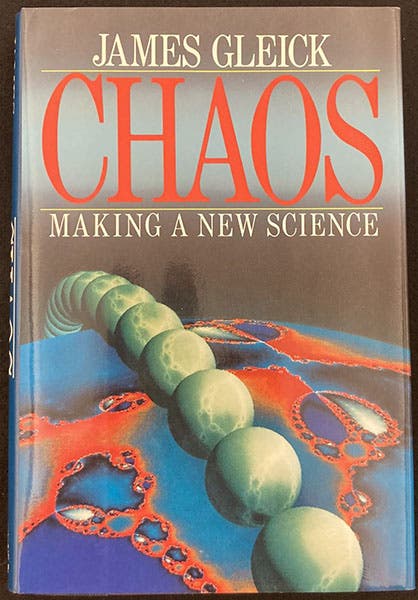

The film Jurassic Park was released on June 11, 1993. Based on the 1990 novel by Michael Crichton, the movie not only provided us with the first truly realistic computer-generated dinosaurs (about which, 30 years later, we are now very blasé), but was also the vehicle that introduced many people to the idea of chaos theory, through the character of Ian Malcolm, our Scientist of the Day today (first image). James Gleick had written a wonderful introduction to chaos theory in 1987, called Chaos: Making a New Science (second image), but I venture that most of the audience for Jurassic Park had not read Gleick’s book when they encountered the “chaotician” Ian Malcolm in Spielberg’s film.

Dust jacket, Chaos: Making a New Science, by James Gleick, Viking, 1987 (author’s copy)

Malcolm, played by Jeff Goldblum, was the conscience of the movie, trying to drive home the point that nature is incredibly complex, with more variables than we can dream of, and it is pure hubris to think that we can tinker with nature and be in control of the outcome. “Life will not be contained— life breaks free,” he says at one point in the film, and in another, “Life finds a way.” In one scene (third image), Malcolm even tries to explain the “butterfly effect”, a central metaphor of chaos theory, to Dr. Ellie Sattler, the paleobotanist. The “effect” is that, in complex systems, a very small change in initial conditions (such as a butterfly flapping its wings in Brazil) can make a very large change in the outcome (the development of a typhoon in Asia).

Chaos theory arose as a result of the work of Edward Lorenz, an American mathematical meteorologist, who, in the early 1960s, was one of the first to use a computer to predict weather patterns. He discovered that the smallest of changes in input would cause vast differences in the predicted output. He announced his conclusions in an article in the Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences in 1963 (we have that issue in our Rare Book Room vault), and chaos theory was born. Lorenz later created the image of a butterfly flapping its wings in Brazil and affecting the pattern of storms in Asia. When Malcolm explains the butterfly effect to Dr. Sattler in the film, he became the first chaotician in cinematic history. We have written a profile on Lorenz.

According to Crichton himself, the character of Malcolm was “provoked” (Crichton’s word) by Heinz Pagels, a physicist who published a book in 1988 called The Dreams of Reason: The Computer and the Rise of the Sciences of Complexity. Right after the book’s publication, Pagels fell to his death from a Colorado peak while attending a conference at Aspen. He was 49 years old. Crichton seems to have been touched by the tragedy, and to have fashioned Ian Malcolm as a tribute. It is a very effective memorial.

In 2018, on the 25th anniversary of the release of Jurassic Park, an inflatable statue of Ian Malcolm (i.e., Jeff Goldblum) suddenly appeared in a London park, right near Tower Bridge on the Thames (fourth image). It was 25 feet long and recreated a famous pose in the movie, after Malcolm had saved the children from the T-rex and was lying on a table in the control center of the park, shirt open, while Richard Attenborough’s character tended to his wounded leg. The statue did not linger long in the park, but thousands of tourists seized the opportunity to take selfies with the lounging Ian Malcom.

The Lego Company has issued many Jurassic World sets and now some 30th-anniversary Jurassic Park ones, but I think only recently has a young (black-haired) Ian Malcolm been included. I have ordered the set named "Triceratops Research," with a minifigure of Ian Malcolm, but it has not yet arrived, so I show here a boring photo from a Lego website. When my set arrives, I will pose Malcolm more artfully, perhaps with T-rex chomping on his leg, and add that image to our collection here.

I leave you with a clip from the film, where Malcolm manages to blurt out all his famous "life breaks free" lines, all at once. You will have to find the shirtless scene on your own.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.