Scientist of the Day - Hyatt Regency Walkways Collapse

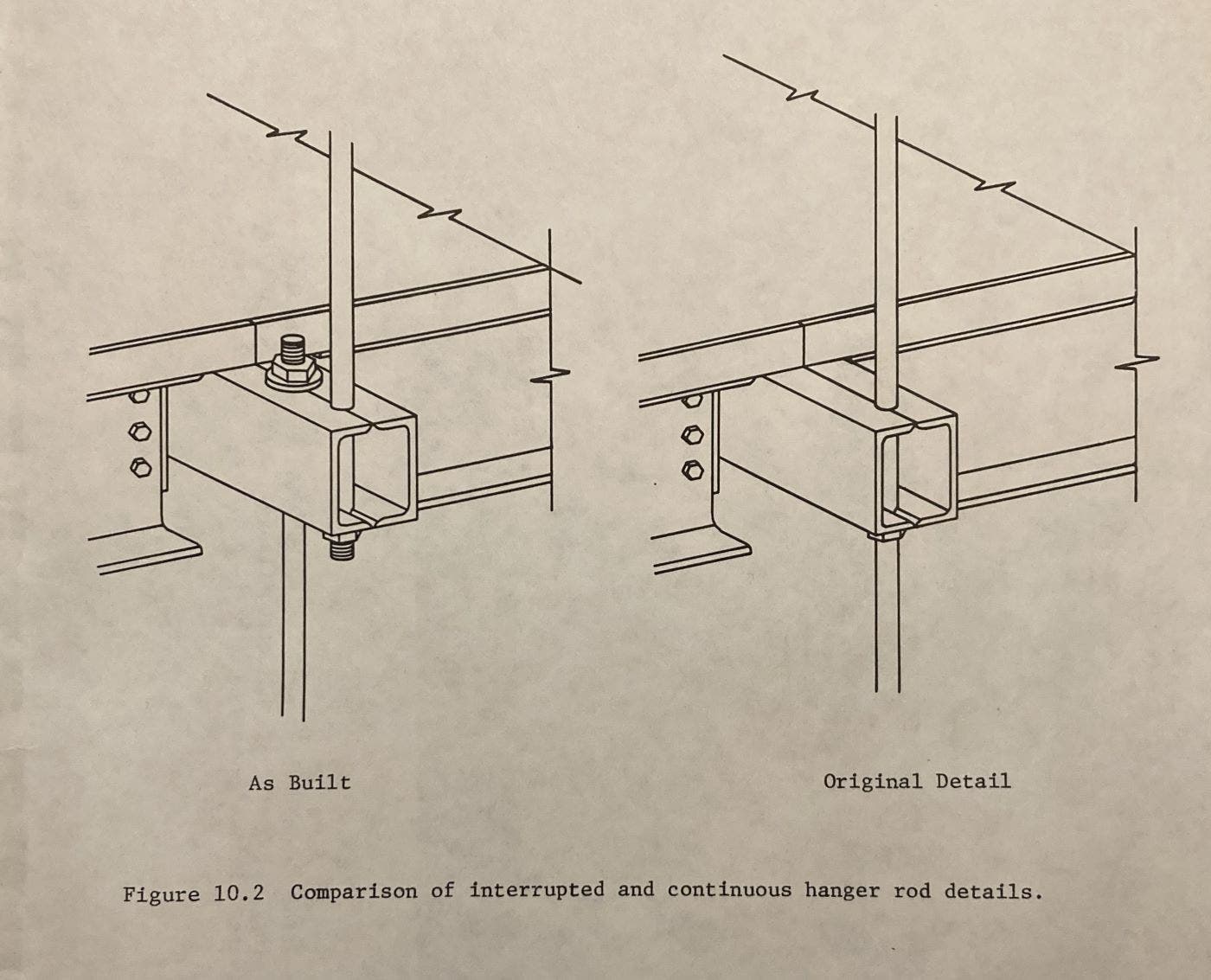

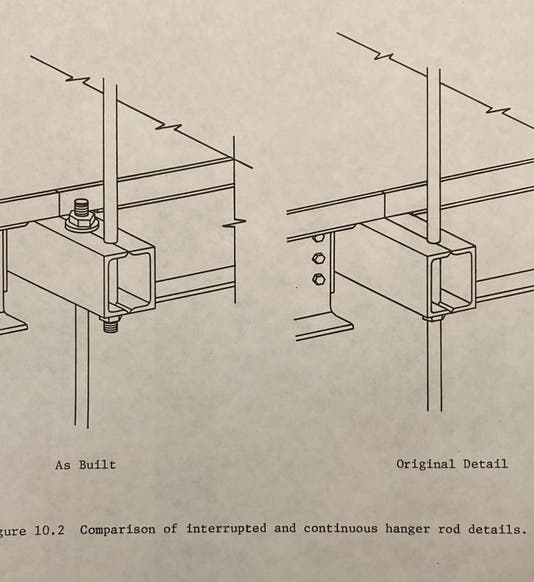

Diagram showing the box-beam and ceiling rod connection for the fourth-floor walkway of the Hyatt Regency atrium, as originally planned (right) and as built (left), Investigation of the Kansas City Hyatt Regency Walkways Collapse, National Bureau of Standards, U.S. Dept. of Commerce (NBSIR 82-2465), p. 247, 1982 (Linda Hall Library)

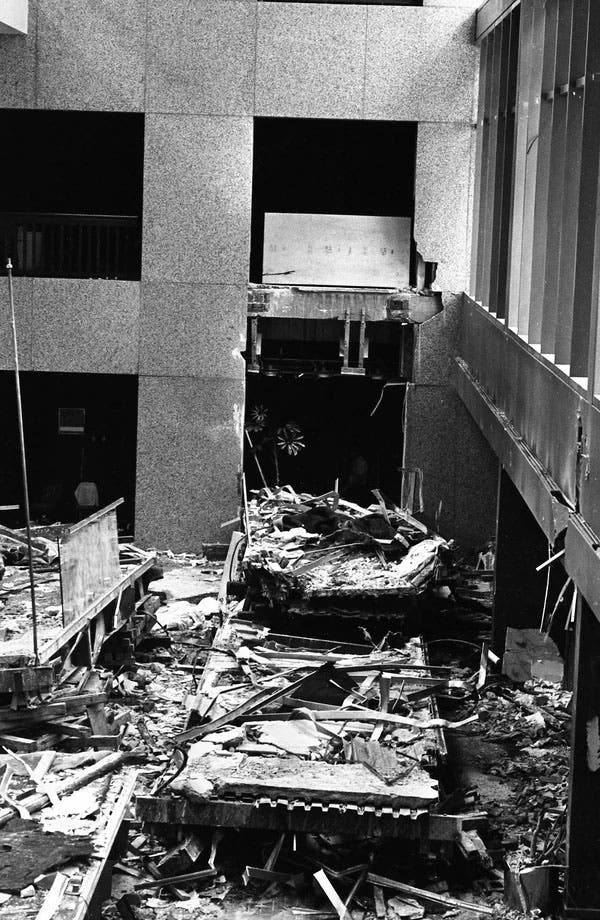

On July 17, 1981, at 7:05 in the evening, the walkways in the atrium of the Hyatt Regency Hotel in downtown Kansas City, Missouri, collapsed and crashed to the floor, killing 114 people gathered for a Friday evening dance, and seriously injuring several hundred more. It was the deadliest accidental structural failure in United States history. We bring up this tragedy because it was caused by a small but disastrous engineering design change that should have been caught, but was not, and it is instructive to see what that change was, and why no one noticed the impact it would have.

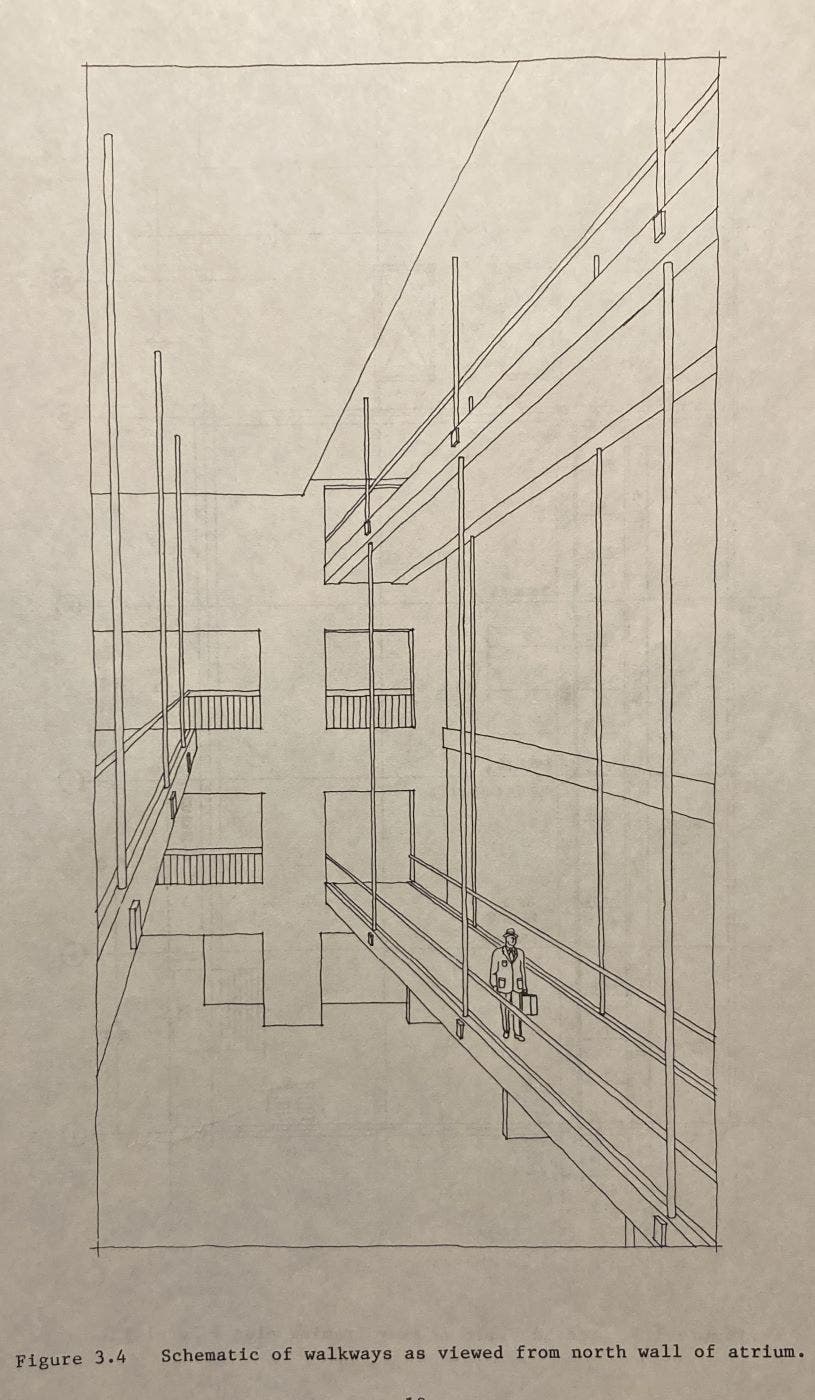

The 50-foot-tall open atrium of the hotel connected the rooms tower with an administrative and service block, and the design incorporated three walkways crossing the atrium, at the second, third, and fourth floor levels. The second and fourth floor walkways were stacked one above the other, and these are the two that failed. In the original design, the stacked walkways were hung from long steel rods that came down from the ceiling (second image). The rods passed through holes in crossbeams in the fourth-floor walkway, secured by washers and nuts, and then down to the second-floor walkway, which was held in place by a second set of washers and nuts.

This was, in hindsight, a poor design, because securing the fourth-floor walkway with nuts meant they would have to be threaded on 20 feet up, which was impossible without threading the entire rod. You can see the original design at the right of the diagram published in the investigation report by the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) in 1982 (first image). Note that the box-beams held up by the rods were not one-piece beams, but were welded together from two U-shaped channels.

Somewhere along the line, an engineer modified the rod-nut design, making what appears to be a significant design improvement. The long rods were divided into pairs, with upper rods supporting the upper walkway, and another set of rods, hanging from the fourth-floor walkway, supporting the second-floor walkway. The change is illustrated at the left of the diagram (first image). I confess that when I first saw this pair of diagrams, I immediately thought that the one on the left was a better design. Lots of people, many trained engineers, must have had the same reaction, because the left-hand design was the one used in building the walkways. But, in fact, they are not structurally equivalent. In the design with the continuous rods, the nut and washer at the fourth-floor level carries the load of the fourth-floor walkway, while the nut and washer at the bottom (not shown in the diagram) carries the weight of the second-floor walkway.

In the modified design on the left, the nut and washer at the end of the upper rod carries not only the weight of the fourth-floor walkway, but that of the second-floor walkway hanging below. Its load had been doubled. Since, as the investigation showed, the original design could barely have accommodated expected loads, the change, doubling the load on the fourth-floor walkway lower nuts, meant that failure was inevitable, especially once the walkways were filled with onlookers.

Investigators were able to pinpoint which rod connection failed first. One of the nuts on the fourth-floor walkway deformed and pulled right through the welded box-beam. Since that nut immediately ceased carrying any weight, its former load was transferred to the nuts on the other rods, which pulled through their beams, and the upper walkway collapsed onto the lower walkway, and then both crashed to the floor and onto the dancers below.

It has been often remarked that a first-year engineering student could have spotted the flaw in the design change, and indeed, the Kansas City Star figured it out within days, long before the NBS investigative team issued their report. But that was after the fact. The truth is, dozens of people, many well-trained engineers, looked at the modified design before it was implemented, and did not see anything amiss. The lesson for future engineers was that design changes need to be scrutinized for structural implications, and that these are often not obvious, and need fresh and repeated examination.

Another lesson for engineers was that, when possible, they need to provide alternate load paths, so that if there is a structural failure, the load can be safely passed along to other structural elements. This is particularly true in the case of bridges, in order to avoid total collapse when there is failure in one part. There were no alternative load paths in the Hyatt walkways design. When one element failed, the others were doomed to follow.

One might wonder if the welded beams contributed to the failure of the Hyatt walkways – after all, some of them did pull apart at the seams where the nuts pulled through. However, the investigative team tested the welds and found that they all met specifications – they were just seriously overloaded. Tubular steel beams without welded seams were available at the time of the construction, but the Investigation did not consider whether they would have made any difference.

I was in Kansas City at the time of the walkways collapse, and my wife, a medical technologist at the time, was called in to her hospital trauma center to help treat victims. It was a terrible time. I have preferred to focus here on the engineering failure, rather than the personal tragedies, because it is an event still painful to recall here in Kansas City. The flaws in the engineering process seem easier to deal with.

I will note that the library’s copy of the official Investigation, from which we drew our two diagrams, has been well-perused, and has had to be enclosed in a protective cardboard box to keep it from falling apart (fifth image). Not all disaster investigative reports are read that thoroughly. I am glad this one has been; it has a lot to tell us about engineering failures. A more accessible and readable account might be Design Paradigms: Case Histories of Error and Judgment in Engineering, by Henry Petroski (1994), which has a section on the walkways collapse.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Using an astrolabe to measure the depth of a well, woodcut in Elucidatio fabricae vsusq[ue] astrolabii, by Johannes Stöffler, 1513 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/a998eb50-55d2-4a88-ace2-a50aa5fa86e7/Stoffler%201.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)