Scientist of the Day - Humphry Sandwith

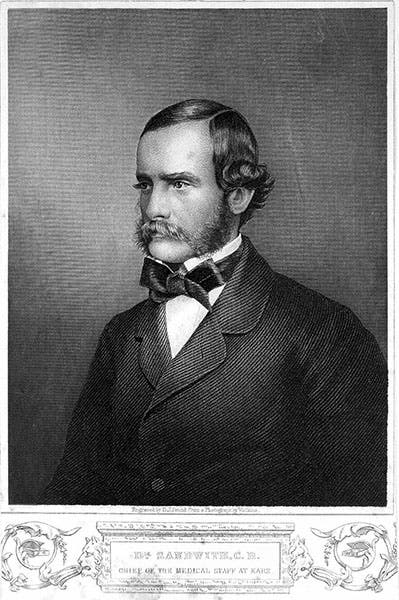

Humphry Sandwith, a British army surgeon, died May 16, 1881, at age 59. Sandwith trained as a surgeon in London and then, not finding a suitable position in England, went to Constantinople and lived there, even spending two years with Henry Layard when Layard discovered and excavated Nineveh. Eventually. Sandwith wound up in the service of Colonel (soon-to-be General) William Fenwick Williams, who was the British advisor to the Turkish Army, as England geared up for the Crimean War against the invading Russian Army. Sandwith was placed in charge of the field hospitals for the Turkish Army.

Sandwith is best known in military and medical circles for his role in the Siege of Kars, a city in eastern Turkey, when he was inside Kars and running the hospitals while city was first assaulted by the Russian army and then besieged. The Turks and the English held off the assaults, but they could not outlast the siege, and the starving city capitulated on Nov. 26, 1855. Sandwith had taken such good care of the wounded, both Turkish and Russian, that when the Russians hauled off most of the conquered English army (including General Williams) as prisoners of war, Sandwith was set free, because he had been so solicitous of the Russian wounded.

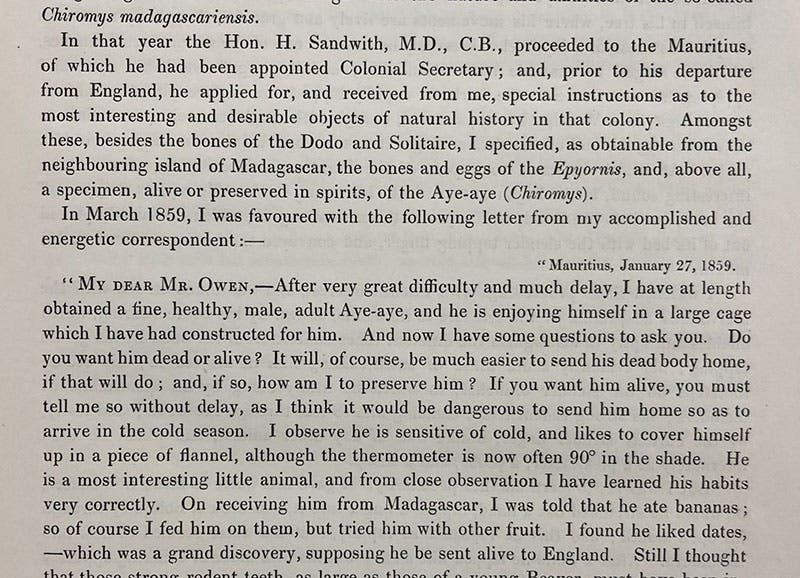

Sandwith returned to England and was widely feted for his bravery, but his career mostly wound down from there. However, in 1857, he was appointed Colonial Secretary to Mauritius, the island just off Africa, near Madagascar, in the Indian Ocean. One of his good friends back home was the anatomist Richard Owen (I have not discovered how the two became acquainted), and now that Owen had a connection in Mauritius, he asked Sandwith to send him some dodo remains (from Mauritius) and an aye-aye, a curious nocturnal primate that is native to Madagascar.

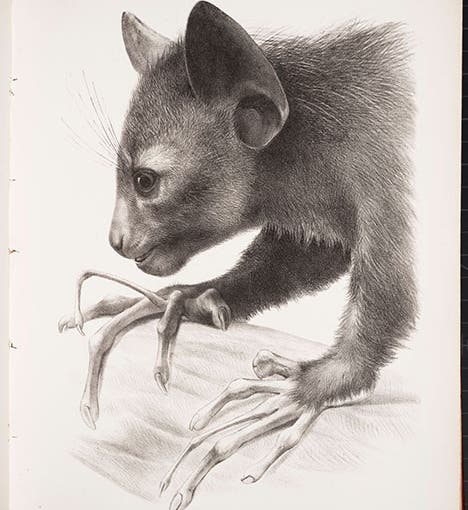

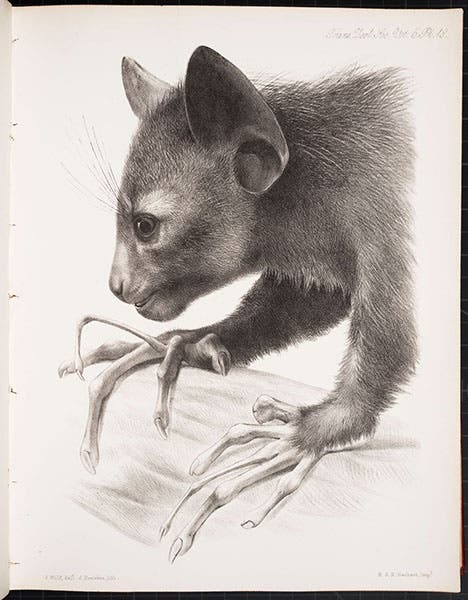

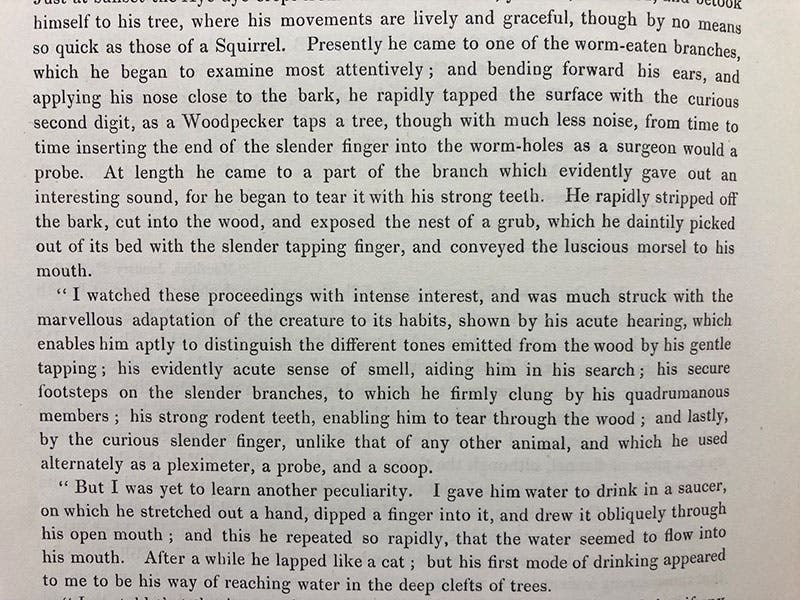

Owen never got his dodo (which had been extinct for nearly 200 years), but Sandwith did come up with an aye-aye. He kept it alive in a small cage and observed it closely. In the beginning, he fed it fruit, which it ate well enough, but when he put a few small branches in the cage, he observed some strange behavior. The aye-aye is distinguished by having a long thin middle finger, quite different from its other digits; rodent-like teeth; and large, forward-facing ears. Sandwith watched the aye-aye drum on the branch with its thin middle finger until it located, by sound, a grub inside the wood, then tear open the wood with its teeth, and extract the grub with its specialized finger. He wrote all this down in a letter to Owen, also asking what he should do with the animal – should he ship it alive or dead? Owen suggested it be chloroformed and preserved and sent to him as a cadaver. He was, after all, an anatomist. And this was done.

Owen published a long article on the anatomy of the aye-aye in the Transactions of the Zoological Society of London in 1866, in which he quoted Sandwith’s letter in full. We reproduce details from the quoted letter in our fourth and fifth images above. Owen also commissioned the noted animal artist Joseph Wolf to bring Sandwith’s gift aye-aye back to life, and the resulting lithographs are so striking that we chose one for display when we did an exhibition in 2013 on lithography and science, called Crayon and Stone (not available online). We show two of those lithographs, as well as a detail, in this post.

It is odd that the most memorable event of Sandwith’s tenure on Mauritius was to purchase an aye-aye from a native of Madagascar, observe it, and send it and his observations to Owen. It was in fact the most memorable event of his entire post-Crimean-War career. I doubt that Sandwith ever imagined the nature of his historical legacy.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.