Scientist of the Day - Hugo De Vries

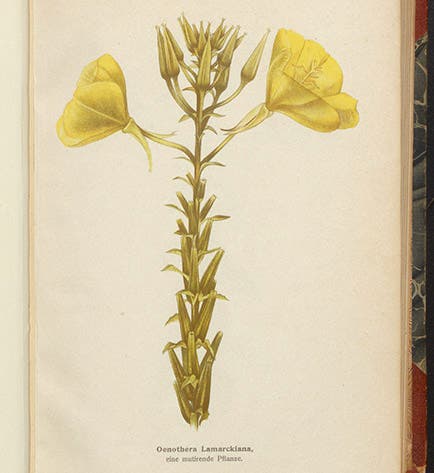

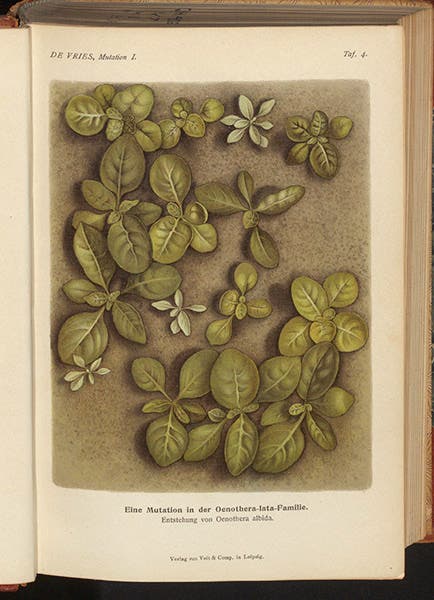

Oenothera lamarckiana, the evening primrose, color plate in Die Mutationstheorie, by Hugo de Vries, vol. 1, 1901 (Linda Hall Library)

Hugo de Vries, a Dutch botanist and geneticist, was born Feb. 16, 1848. De Vries was interested in botany from his earliest days, and he studied the science at Leiden and then in Heidelberg and Würzburg in Germany. He was especially impressed by the teaching of Julius Sachs, who brought the study of plants into the laboratory and made it an experimental science. Botany was traditionally a part of natural history and at the time was studied almost exclusively in the field or in museums and herbaria.

De Vries became director of the Botanical Institute and Garden at the University of Amsterdam in 1885, and he undertook a long series of hybridization experiments with primroses. He was looking for support for his theory that hereditary traits are passed on by heredity particles – pangenes, he called them – that were independent of one another (segregated, to use the scientific word) and were contributed by each parent to the offspring. A Moravian monk named Gregor Mendel had not only proposed a similar idea about thirty ideas earlier, but he had supported his theory with seven years of observations and experiments on pea plants, and furthermore, he read two papers with his results to the Natural History Society of Brno in 1865 and then published them in the Society’s journal, which was distributed reasonably widely throughout Europe. That said, by the time of Mendel’s death in 1884, his work had almost completely disappeared from scientific view, and de Vries initially knew nothing of Mendel's discoveries.

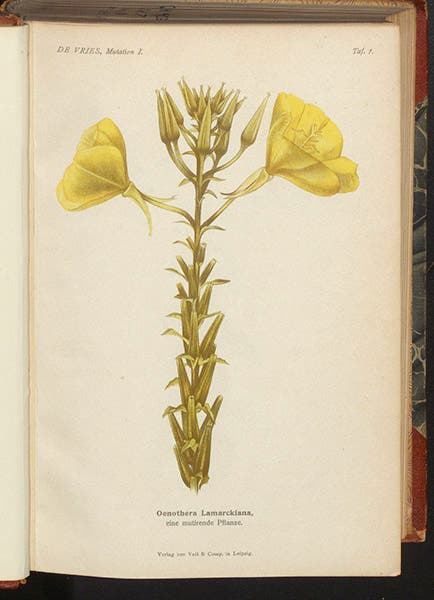

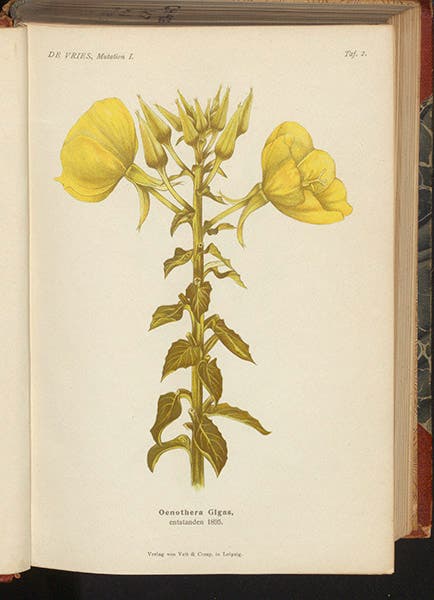

De Vries discovered that primroses occasionally produced “sports” – mutations as de Vries called them – which were significantly different from the wild plant, and which, most importantly, bred true, so that the offspring of the sports did not revert to being normal wild primroses. The evening primrose was actually an American plant that had been brought to Europe in the 17th century and which became popular in gardens, because of its beautiful flowers. The wild primrose was named Oenothera lamarckiana (first image). One of the first mutations de Vries noticed was a primrose with larger flowers and other notable differences from O. lamarckiana; he called it O. gigas (third image), and it bred true. Another had quite different, round leaves, and de Vries named it O. lata (fourth image).

In 1890, evolution was commonly accepted by botanists, but not Darwin’s mechanism of natural selection, which attributed evolutionary change to the accrual and selection of small, random variations that were favorable to the organism. No one could understand why favorable variations did not just blend back into the general population. Mendel had shown that genes do not blend, but no one knew about Mendel.

Oenothera gigas, a primrose “sport” or mutation that appeared spontaneously, but bred true, color plate in Die Mutationstheorie, by Hugo de Vries, vol. 1, 1901 (Linda Hall Library)

De Vries greatly admired Darwin, but he wanted no part of natural selection either. His work with primroses gave him a different idea. Perhaps evolution proceeded by large changes – by mutations. Since a mutation was practically a new species, it would not blend back in with an older species. Mutations were what nature selected, not small variations. He ran across Mendel's papers in 1899, and seems to have thought about pretending he hadn't, but two other researchers rediscovered Mendel about the same time, and making the best of what must have been a difficult situation, de Vries publicly credited Mendel with anticipating his work in a paper published in the spring of 1900. Since de Vries was by far the best known of the trio of Mendel rediscoverers, the revival of Mendel has often been attributed to him.

Oenothera lata, another primrose mutation with round leaves and that bred true, color plate in Die Mutationstheorie, by Hugo de Vries, vol. 1, 1901 (Linda Hall Library)

Between 1901 and 1903, de Vries published a massive two-volume work: Die Mutationstheorie: Versuche und Beobachtungen über die Entstehung von Arten im Pflanzenreich (The Mutation Theory: Experiments and Observations about the Genesis of Species in the Plant Kingdom). We have this work in our collections, and we show here some of the beautiful paintings of primroses and their mutations that appear in the work.

Title page, Die Mutationstheorie, by Hugo de Vries, vol. 1, 1901 (Linda Hall Library)

De Vries’ mutation theory was extremely popular for about ten years, and he had considerable influence on Thomas Hunt Morgan, who started looking for mutations in fruit flies as a consequence and who came up the chromosome theory of inheritance by 1915. But the problem with the mutation theory is that no one, including de Vries, could find other examples of spontaneous mutations outside of primroses. Variations were everywhere, but mutations were not. If nature selected mutations, where were they? As researchers came to understand Mendel better, they began to see how Mendelian genetics and Darwinian natural selection could work together to produce and preserve evolutionary change. By 1930, geneticists and evolutionary biologists like Ronald A. Fisher and J.B.S. Haldane were formulating the Modern Synthesis, and de Vries’ mutation theory was left on the cutting-room floor.

Since de Vries chose the wrong fork in the road, he is not as well known to the general public as Darwin and Mendel, and you won’t find many statues of de Vries in public squares, even in the Netherlands. I couldn’t even find a primrose variety named in his honor. But he does have a laboratory named for him in Amsterdam.

There is an excellent chapter on de Vries and his primroses in the delightful book, A Guinea Pig’s History of Biology, by Jim Endersby (Harvard Univ. Press, 2007).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.