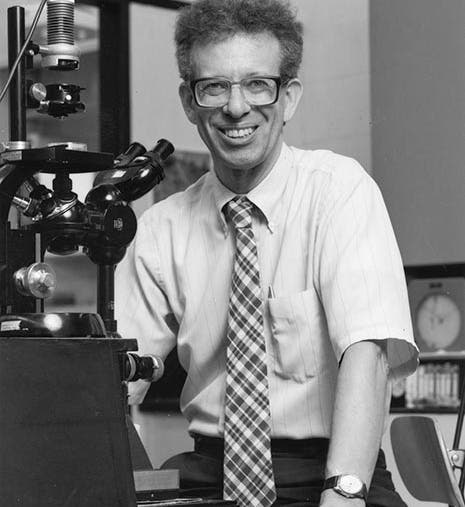

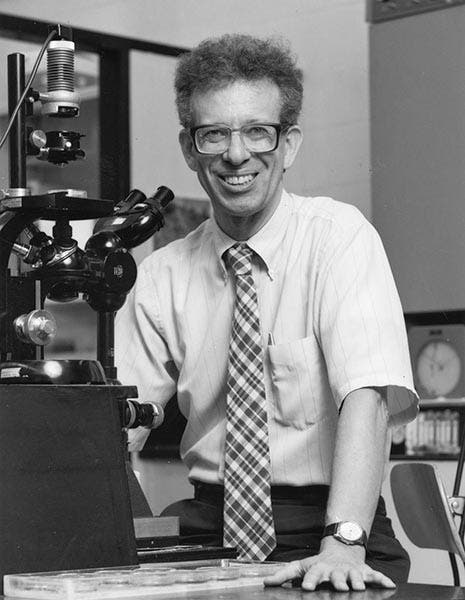

Scientist of the Day - Howard Temin

Howard Martin Temin, an American virologist and cell biologist, died Feb. 9, 1994, at age 59. Temin came from Philadelphia, attended Swarthmore, and did graduate work at Caltech. In Pasadena, he became interested in bacteriophages, or phages, which are viruses that attack bacteria. For his PhD, he studied one particular virus, Rous sarcoma virus, which can cause cancer in chickens. Temin was especially interested in discovering the mechanism by which a virus causes a cell to become malignant. He became convinced that the Rous sarcoma virus, which is an RNA virus, meaning its own genetic material is RNA, has the capacity to change the DNA of the host cell, so that it will make copies of the virus. This provirus theory, as Temin called it, very much went against the grain of post-Watson-Crick genetics, which maintained that RNA could never feed back and alter the DNA structure of a gene. It was thought that the flow always went the other way, from DNA to RNA to protein.

Temin moved to the cancer lab at the University of Wisconsin in Madison in 1960 and continued his work. In 1964, he was able to demonstrate the truth of his premise; cells infected with Rous sarcoma virus do exhibit changes in their DNA. In 1970, Temin discovered an enzyme, reverse transcriptase, that is coded for by the virus and which enables the viral RNA to be copied in DNA in the host cell. This was quite unexpected at the time, although we now know that viruses such as HIV and Hepatitis B use exactly the same method of RNA-DNA transcription to infect host cells. Reverse transcriptase was discovered independently by David Baltimore at MIT, and Temin, Baltimore, and Temin's mentor at Caltech, Renato Dulbecco, were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology/Medicine in 1975. Temin was 39 years old.

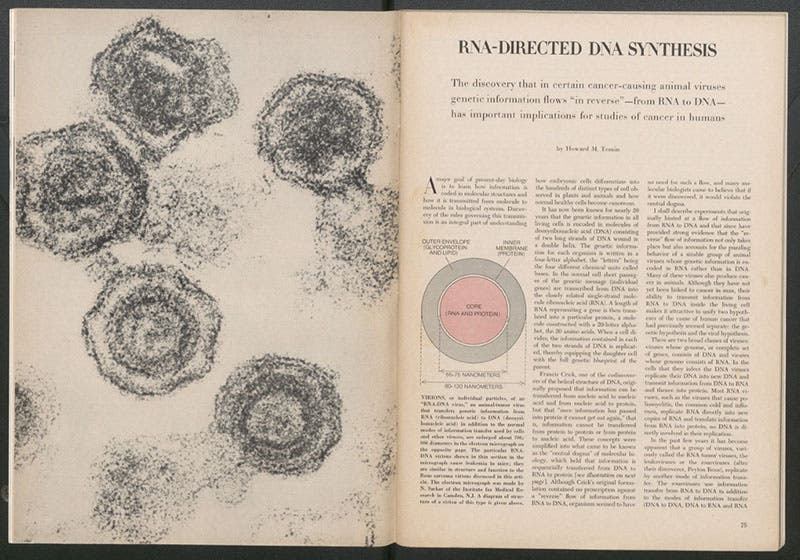

First page of “RNA-directed DNA Synthesis," by Howard M. Temin,Scientific American, vol. 226(1), Jan. 1972; the article frontispiece shows virions, or particles of an RNA-DNA virus (author’s copy)

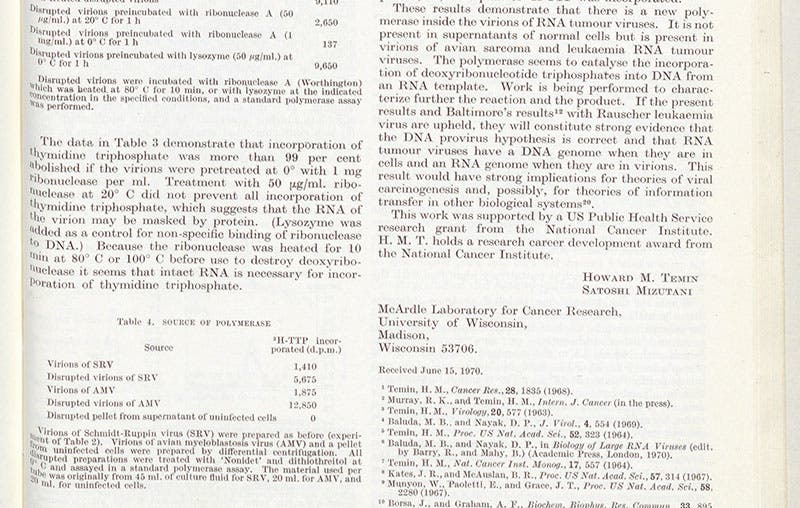

Temin’s discovery of reverse transcriptase was announced in a short article in Nature in 1970, where it directly followed Baltimore’s paper; we can see here the end of the paper by Temin (and his colleague Mizutani) (second image). These papers, brilliant though they are, cannot really be comprehended by the likes of most of us non-virologists. But in 1972, Temin published a paper on reverse transcription in Scientific American, called “RNA-directed DNA Synthesis” (third image). Like most papers in Scientific American, this is a paper that most of us can read with profit and comprehension, and if you really want to understand what Temin did, I recommend that you look it up, in the January 1972 issue, pages 24-33. I would argue that before someone is given a Nobel Prize, they should be required to write an article for Scientific American, explaining their work to a non-specialist audience. If they cannot do so – and many cannot – then the prize should be awarded to someone else.

Temin was passionate about many things, especially cancer. When he gave his Nobel Prize address, he rebuked those in the audience who were smoking, including the Queen of Denmark, stating that smoking is the single greatest cause of avoidable cancer, and he could not understand why this fact was being ignored.

Temin attracted lots of job offers after 1975, as Nobelists tend to do, but he liked Madison, and he stayed there. He rode his bike to the cancer lab each morning along the Lakeshore Path that runs along Lake Mendota, and when the snows came, he walked. I was doing my graduate work in Madison at this time and walked that same path often; I surely if unknowingly encountered Dr. Temin more than once (although in January, he would not have met me on that path). In the cruelest of ironies, Temin, a lifelong non-smoker and anti-smoker, died of lung cancer in 1994. In 1998, the University renamed Lakeshore Path, and it became the Howard M. Temin Lakeshore Path. I cannot think of a better memorial.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.