Scientist of the Day - Howard Florey

Howard Florey, an Australian pathologist, was born Sep. 24, 1898. Florey played a major role in isolating and mass-producing penicillin just in time for those injured in World War II. Most people learn in school that Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin in 1928, when he noticed that some bread mold, which had infiltrated one of his petri dishes, was killing the resident bacteria. For his discovery, Fleming shared the Nobel prize for Physiology/Medicine in 1945, and in 1999, long after his death, Fleming was listed by Time Magazine as one of the 100 most important men of the century. The trouble is, there were four men involved in bringing penicillin to market as an antibiotic, and of the four, Fleming was the least important. He did discover the anti-bacterial properties of bread mold, and he did name the secret ingredient penicillin. But Fleming was unable to isolate penicillin from the mold, and he wasn’t sure that, even if it could be isolated, it would be useful in fighting human infections. It was Florey who accomplished what Fleming was unable to do.

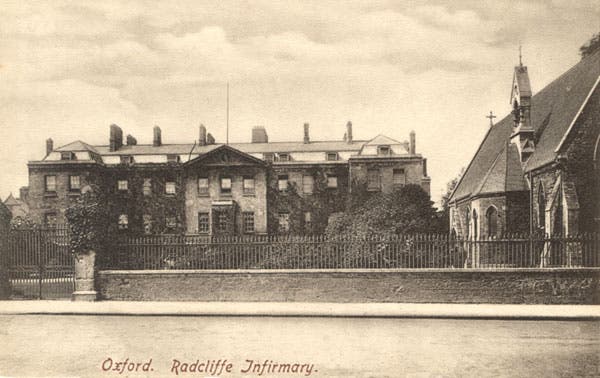

Working with Ernst Boris Chain at the Radcliffe Infirmary at Oxford in the late 1930s (second image), Florey and Chain figured out how to isolate penicillin and, within a year, how to mass-produce it, and they were significantly aided by a student, Norman Heatley. Within five years, billions of units of penicillin were being produced in Britain and the United States, hundreds of thousands of lives were being saved, and Fleming played no role in any of this. When the Nobel Prize was awarded for the discovery, Florey and Chain shared it with Fleming, but since there is a limit of 3 co-recipients for a Nobel award, young Heatley was left out, even though his contribution was vital.

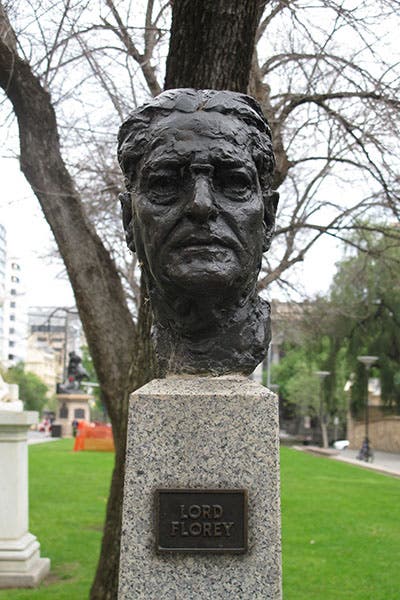

Yanks and Brits may cling to the Fleming myth (see the New York Times headline for Oct. 26, 1945, third image – “Fleming and two co-workers” indeed), but in Australia, there is no doubt who deserves credit for the success of penicillin. In 1965, Florey was raised to a life peerage, with the title of Baron Florey of Adelaide, and Australians are fond of pointing out that his baronetcy outranks the knighthood that Fleming received. Florey has a handsome bust on the grounds of Government House in Adelaide.

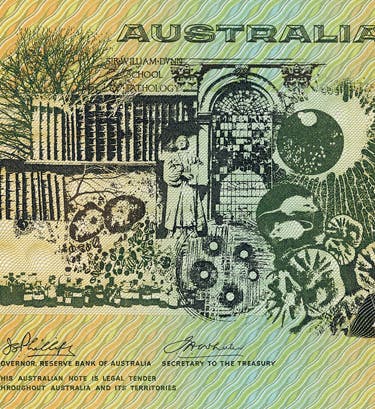

In 1973, Australia issued a $50 note with Lord Florey’s portrait on the front (first image). Interestingly, the reverse carries the portrait of Ian Clunies Ross, an important science adviser and administrator during the War and afterwards, sort of the Vannevar Bush of Australia. That’s two scientists on one bill. Australian authorities do appear to have their heads on straight.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.