Scientist of the Day - Horatio Austin

Admiral Horatio Thomas Austin, a British naval officer, died Nov. 16, 1865, at age 64. In 1850, then Capt. Austin led a four-ship expedition into the Arctic archipelago in search of the crew and ships of Sir John Franklin, which had left England in 1845 in search of a Northwest Passage and had not been heard from since. Austin’s small fleet consisted of two sailing ships, HMS Resolute and HMS Assistance, and two screw-driven steam tenders, HMS Pioneer and HMS Intrepid. Austin was somewhat of an authority on steam-powered vessels for the Royal Navy, and that may have been why he was selected to command this mission.

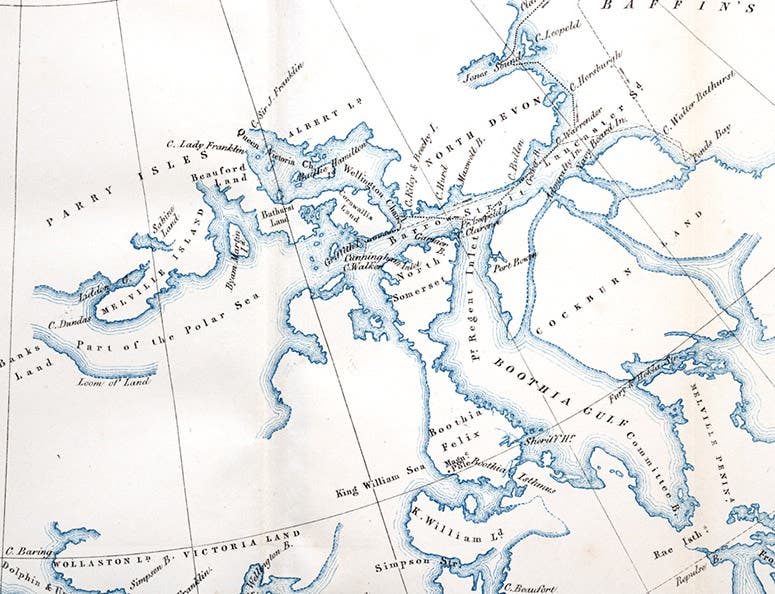

Austin’s four ships sailed and steamed up Baffin Bay and made their way through Lancaster Sound and Barrow Strait (see map, fourth image), following the presumed paths of Franklin’s vessels, to Griffith Island, where they prepared the ships to be frozen into the ice for the winter, as had been the custom with British Arctic expeditions since that of William Edward Parry in 1819. There is a lovely lithograph of Austin’s four ships in their winter harbor in the published narrative of the commander of HMS Pioneer, Sherard Osborn (third image, just below).

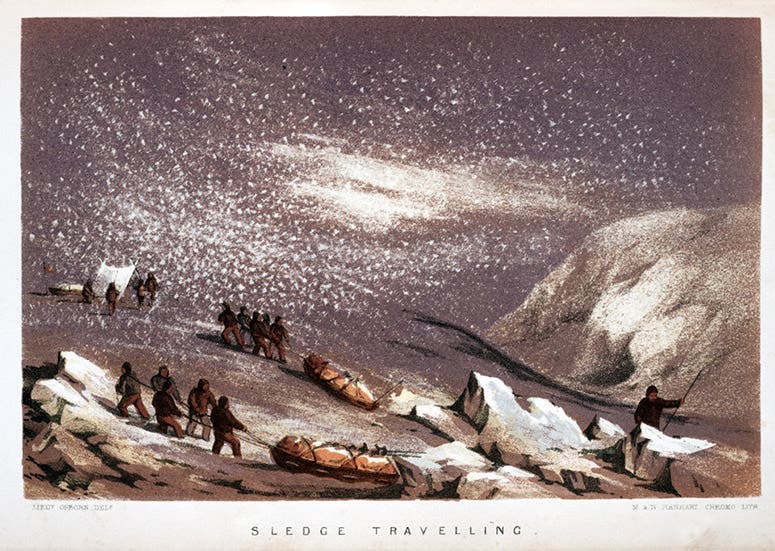

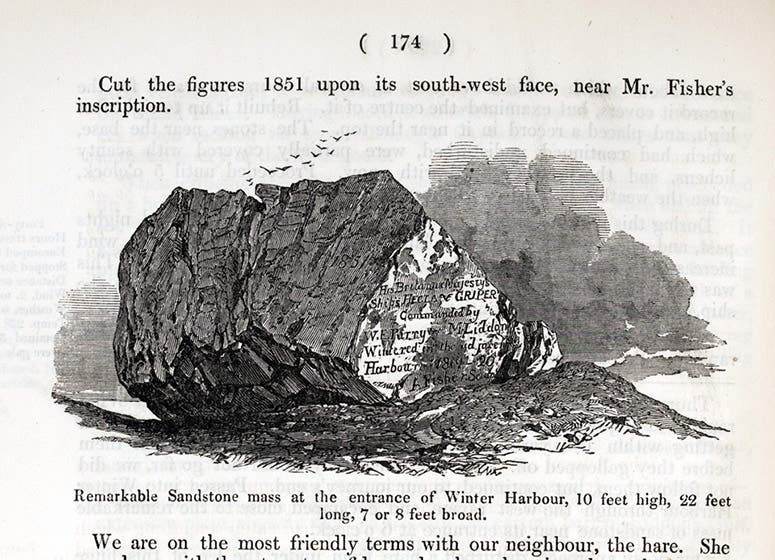

One aspect of this expedition that was not at all typical is that once the ships were immobilized, Austin sent out eight search expeditions by sledge, which was an innovation in Arctic exploration. This was certainly an improvement on the previous practice of sitting idly in the ships from September until June, waiting for them to thaw out. With all due respect to Capt. Austin, the idea for sledge exploration seems to have come from Lt. Francis McClintock, commander of the Intrepid. The sledge expeditions were formally organized, each sledge having a name, a commander, and a flag. McClintock’s own sledge was HMS Perseverance (HMS standing in this case for “Her Majesty’s Sledge”). He took it out in the spring of 1851, and his men hauled it 760 miles in 80 days. They reached Melville Island, where Parry had wintered in 1819-20, and found a rock that one of Parry’s men had carved with an inscription. McClintock copied it down, and it was printed in one of the so-called Arctic Blue Books published by the Admiralty between 1850 and 1855 (sixth image, below).

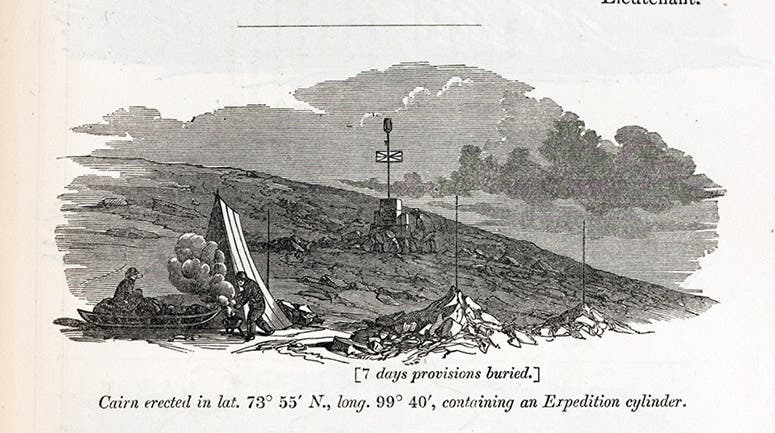

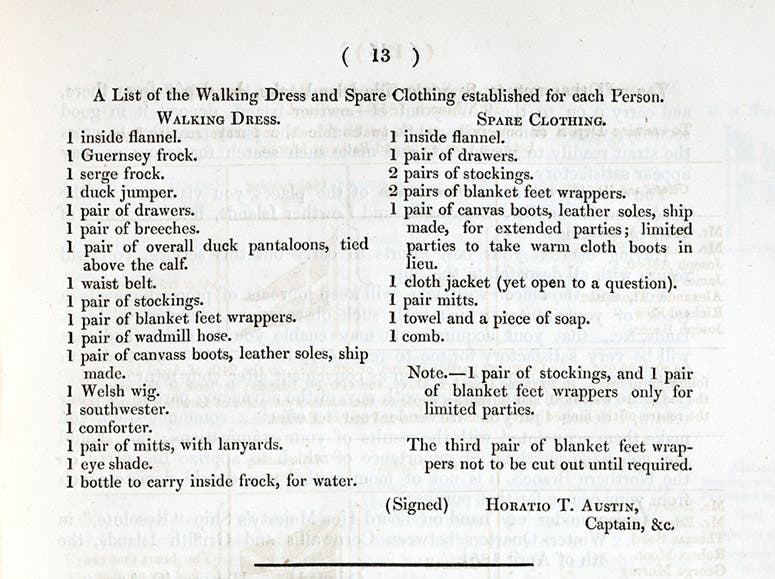

Austin’s sledge crews also left caches of food and even small boats, marked with cairns, at selected locations on some of the islands of the archipelago. The same Arctic Blue Book that reproduced “Parry’s rock” also included small wood engravings of the cairn-building and food-stashing; we include one of those here (seventh image). This Blue Book also has a wealth of the kind of information one never finds in the official narratives, such as a list that Austin drew up of the clothing allotment for each member of a sledge expedition (eighth image). Since the temperature during the late winter was often 40 below zero (Celsius or Fahrenheit, take your pick), you can decide how well protected Austin’s men were against the Arctic cold.

Austin did not find the Franklin expedition, or any traces of where they had gone. Unbeknownst to everyone at that time, the ships had reached King William’s Island, well south of Griffith Island and Melville Island. In August of 1851, Austin got into a disagreement with William Penny, leader of a private search effort financed by Lady Jane Franklin, and after their tiff, both expeditions abruptly left the Arctic and went home, to the consternation of both Lady Jane and the Admiralty.

For some reason, Austin did not write his own narrative of his expedition. Fortunately, Sherrard Osborn did, and our first four images (excepting the portrait) come from Osborn’s delightfully titled book, Stray Leaves from an Arctic Journal (1852). One of Austin’s ships made its own place in history. HMS Resolute returned to the Arctic as part of the Belcher expedition, 1852-54, was abandoned by Belcher, thawed out on its own and drifted out into whaling waters, where it was found by Americans, who rehabilitated the ship and returned it to Queen Victoria. Later, when the ship was decommissioned, the Queen had two desks built from the beams, and one of the Resolute desks now sits in the Oval Office at the White House. You can read a little more about the adventures of the Resolute in our posts on Edward Everett Hale and Henry Kellett, commander of the Resolute on her second Arctic journey.

If you would like to learn more about the entire “search for Franklin” saga, you might consult our exhibition catalogue, Ice: A Victorian Romance; if you start with Section V and continue through items 36 to 51, you will get an overview, with images, of the search and its outcome.

Austin’s portrait (second image) was painted in 1860 by Stephen Pearce, who did portraits of nearly every Royal Navy commander who ventured into the Arctic. We showed some of these in our post on Pearce.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.