Scientist of the Day - Horace Wells

Steel engraving of Horace Wells (c. 1912) (Clendening History of Medicine Library)

Horace Wells, an American dentist, died in a New York City prison cell on January 24, 1848, at the age of thirty-three. The eldest son of a Vermont farmer and miller, Wells had briefly considered becoming a minister before opting for a career in dentistry. In 1834, he went to Boston to pursue an apprenticeship, the only form of dental education available in the United States prior to the 1840 establishment of the Baltimore College of Dental Surgery. Following two years of study, he relocated to Connecticut and began offering his services to the citizens of Hartford in the spring of 1836.

By all accounts, Wells was a successful dentist. In between extracting teeth and filling cavities, he found time to publish a brief treatise on oral hygiene and started taking on students of his own. He also demonstrated an innovative streak and teamed up with one of those students, William T.G. Morton, to market a new, noncorrosive solder to attach artificial teeth to gold plates. Although their partnership fell apart in the fall of 1844, Wells would reach out to Morton a few months later to discuss a far more promising invention.

On the evening of December 10, 1844, Wells and his wife attended a “Grand Exhibition” at Hartford’s Union Hall that was organized by an itinerant showman named Gardner Colton. Colton, a failed medical student, had gained notoriety for his public lectures showcasing the intoxicating properties of nitrous oxide. During the course of the lecture, Colton invited volunteers to inhale the gas while the audience watched their reactions. Among those who took the stage in Hartford that evening was an apothecary clerk named Samuel Cooley, who injured his legs by running into a bench. After the show had concluded, Wells realized that Cooley had not noticed he was hurt until the effects of the gas had worn off. This observation led him to wonder if he could use nitrous oxide to eliminate pain during dental surgery.

After consulting with Colton and his former student John Riggs, Wells proposed to test the idea by inhaling laughing gas and having one of his wisdom teeth removed. The following morning (December 11, 1844), the three men gathered in Wells’ office for what would normally be an incredibly painful surgery. Colton set up his equipment and presented Wells, who was seated in the operating chair, with a bag full of nitrous oxide. As Riggs recalled later, “Wells took the bag in his lap--held the tube to his mouth & inhaled till insensibility relaxed the muscles of his arms--his hands fell on his breast--his head dropped on the head-rest & I instantly passed the forceps into the mouth--onto the tooth and extracted it.” Shortly thereafter, Wells recovered from his stupor and confirmed that he had not felt anything throughout the procedure.

Although the English chemist Humphry Davy had published a book in 1800 that speculated about medical uses for nitrous oxide, Wells’ experiment was the first time that the gas had been successfully used as a surgical anesthetic. Over the next few weeks, he performed several more tooth extractions using the gas before deciding the time had come to share his discovery with the broader medical community. To that end, he returned to Boston in January 1845, where his former partner William Morton introduced him to John Collins Warren, the head of surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital.

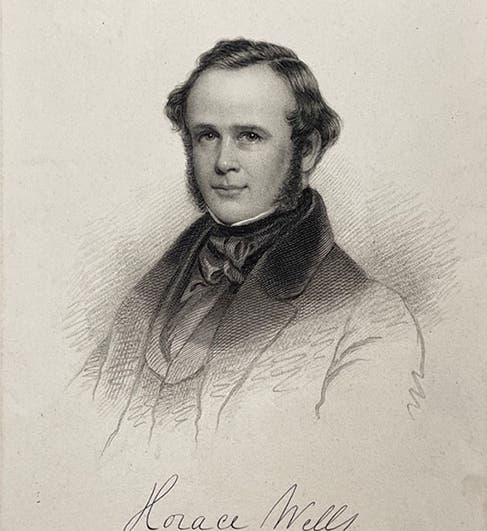

Warren was intrigued by Wells’ findings and asked him to present them to a group of Harvard medical students. He also invited the dentist to demonstrate his gas during an upcoming amputation, but the patient decided to postpone the surgery. Instead, Wells persuaded one of Warren’s students to have a tooth removed to showcase nitrous oxide’s analgesic properties. Everything appeared to be going smoothly at first, but after a few minutes the student began to groan, leading some in the audience to assume he was in pain. The crowd swiftly turned on Wells. They denounced him as a fraud and a “humbug,” even after his patient confirmed that he had experienced almost no discomfort (second image).

The following morning, a humiliated Wells retreated to Hartford. His time in Boston had proven so stressful that he suspended his dental practice, though he continued to provide nitrous oxide to patients visiting his old friend John Riggs. He also stayed in contact with William Morton, who remained intrigued by the idea of a surgical painkiller. By the summer of 1846, Morton had started experimenting with sulfuric ether (known today as diethyl ether), another compound whose vapors were inhaled recreationally during the early nineteenth century. He concluded that ether would be a more effective anesthetic than nitrous oxide and persuaded John Collins Warren to schedule a demonstration. On October 16, 1846, Morton administered ether to a Boston housepainter named Gilbert Abbott, who had come to Massachusetts General Hospital to have a tumor removed from his neck. Once Abbott was unconscious, Warren was able to complete the operation without incident. Perhaps recalling the local reaction to Wells’ nitrous oxide experiments the previous year, he addressed the audience in the operating theater: “Gentlemen, this is no humbug.”

Unlike Wells, who had freely shared information about the use of nitrous oxide with other Hartford-area dentists, Morton’s immediate response to the success of the so-called “Ether Day” operation was to secure a patent for his invention. He attempted to distance himself from Wells, who had demonstrated the efficacy of inhalational anesthetics nearly two years earlier, and Charles Jackson, a physician and chemist with whom he had discussed possible medical applications of sulfuric ether. Morton’s efforts to claim priority for the discovery of anesthesia would later provoke objections from Crawford Long, a Georgia-based doctor who had used ether to perform several surgeries in 1842.

For his part, Wells responded to Morton’s assertions by describing his nitrous oxide experiments in the December 9, 1846 edition of the Hartford Courant. He noted that even if Morton and Jackson were now promoting the use of a different gas, he had introduced the fundamental principle during his visit to Boston the previous year. Morton and his allies responded by offering to purchase Wells’ rights to the invention of anesthesia. When he refused, they began writing articles refuting his claims in Boston’s newspapers. Wells, in turn, published what he termed “a true and faithful history of the discovery” in the spring of 1847.

Over time, the controversy began to take its toll. By the end of 1847, Wells had grown disinterested in dentistry and began devoting more attention to a scheme to sell European reproductions of famous paintings. He began traveling to New York on a regular basis to pursue this new business venture, and in January 1848, he moved into an apartment in midtown Manhattan. Around the same time, he started experimenting with chloroform, a powerful anesthetic that had recently been popularized by the Scottish physician James Simpson. As had been the case with nitrous oxide, Wells opted to test the new drug on himself, little realizing its addictive properties or effects on his behavior.

The tragic consequences of Wells’ chloroform habit became apparent on January 21, 1848 (his thirty-third birthday), when he was arrested for throwing sulfuric acid at two women while under the drug’s influence. When he recovered his senses, Wells found himself imprisoned in the New York Halls of Justice and House of Detention, nicknamed “The Tombs.” He was profoundly ashamed of his behavior and spent the next three days agonizing over the consequences that his arrest would have on his wife and son. Finally, on January 24, 1848, he wrote an apologetic letter explaining his actions and begging forgiveness from God and his family. Once he had finished, he took a final dose of chloroform that he smuggled into his cell with his toiletries and used a razor to sever his femoral artery. A guard discovered his body the following morning (third image).

Bronze death mask of Horace Wells made from a plaster cast taken after his suicide on January 24, 1848. This is a replica of the original mask, which is housed at the Boston Medical Library. (Clendening History of Medicine Library)

Contrary to his fears, the circumstances surrounding Wells’ death did not significantly detract from his legacy. Despite Morton’s ongoing efforts to position himself as the inventor of anesthesia, the American Dental Association officially credited Wells with the discovery in 1864, and the American Medical Association followed suit in 1870. In 1874, the city of Hartford paid homage to its adopted son by commissioning Truman Howe Bartlett to create a sculpture of Wells in Bushnell Park. (fourth image). (Bartlett’s son, Paul Wayland Bartlett, became a well-known sculptor in his own right and was featured as our Scientist of the Day exactly one year ago.)

Horace Wells’ life was cut tragically short, but both his wife (Elizabeth) and son (Charles) lived long enough to see him receive recognition for his contributions to modern medicine. After Elizabeth died in 1889, she was buried next to her husband in Hartford’s Old North Burying Ground. In 1908, Charles Wells moved his parents’ bodies to Cedar Hill Cemetery and arranged for the construction of a new monument honoring his father (fifth and sixth images). The bronze tablet on the front features a merciful angel delivering relief to a reclining figure. The accompanying caption embodies Horace Wells’ dream and the fundamental promise that the anesthesiologists who follow in his footsteps continue to make to their patients: “There Shall Be No Pain.”

Monument for Horace Wells, designed by Louis Potter and Montague Flagg (1909), Cedar Hill Cemetery, Hartford, CT. The monument is flanked by a pair of female heads. The one on the right has her eyes closed and is positioned over a bouquet of poppies and the motto “I Sleep to Awaken.” The one on the left has her eyes open and replaces the poppies with morning glories. Her motto reads “I Awaken to Glory.” (Photographs by author)

Benjamin Gross, Vice President for Research and Scholarship, Linda Hall Library. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to grossb@lindahall.org. Special thanks to Jamie Rees and Ryan Fagan at the Clendening History of Medicine Library at the University of Kansas Medical Center for assistance locating images for this post.

![Using an astrolabe to measure the depth of a well, woodcut in Elucidatio fabricae vsusq[ue] astrolabii, by Johannes Stöffler, 1513 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/a998eb50-55d2-4a88-ace2-a50aa5fa86e7/Stoffler%201.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)