Scientist of the Day - Holless Wilbur Allen

Image by Craig Stanke

Holless Wilbur Allen, Jr., an American inventor and manufacturer, may be the most unsung inventor in American history. In the mid-1960s, Allen took a device, the bow, that had stood relatively unchanged for about 7000 years, and transformed it into a more powerful, more accurate device shooting faster arrows with less effort from the archer. Allen invented the compound bow. The hunting bows of his day, recurve bows or longbows that looked very much like bows used during the Hundred Years War, required about 70 pounds of force to draw the string (called draw weight), and shot arrows with a velocity of perhaps 175 feet per second (fps). The most inconvenient feature of such a bow was that you had to maintain that 70 pounds of draw while trying to aim at a target, which was very difficult to do.

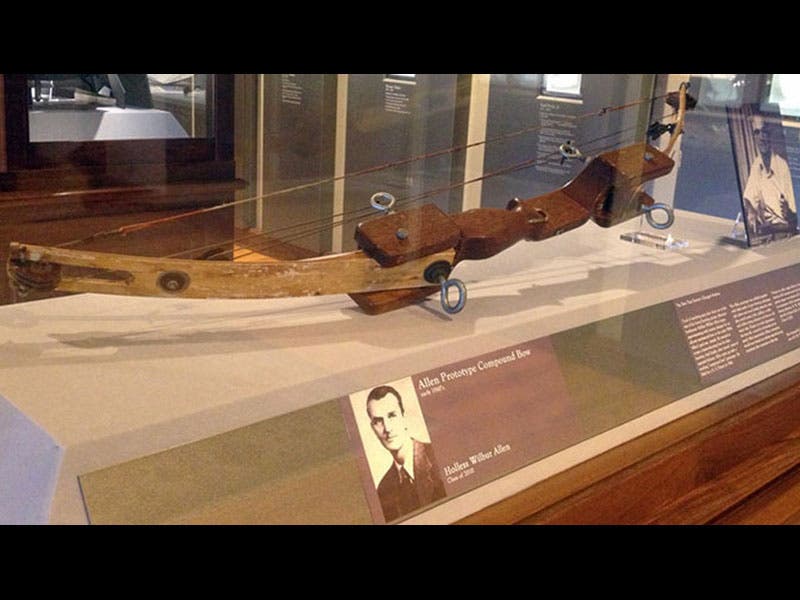

So Allen read some books on physics, learned about energy storage and transfer, and tried to find a better way to take the energy of the draw and store it more efficiently in the bow limbs, while reducing the continuous effort required from the archer. He found he could do this by adding pulleys and extra cables to the limbs of the bow, which allowed the draw power to be constant, rather than gradually increasing as with the longbow, and he also found a way to arrange the pulleys so that the weight of the draw was greatly reduced during the last inch of so, so that one could aim the bow without straining at the same time to keep the bowstring under tension. We see an Allen prototype bow on display in our first image.

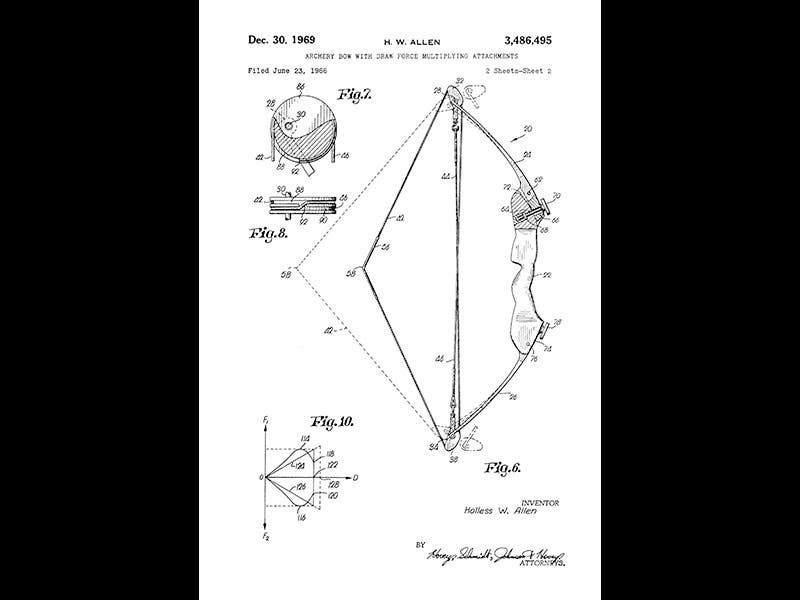

Allen patented his compound bow in 1969 (second image), and although there was a great deal of initial resistance (that first bow was rather ungainly), he finally found a bow manufacturer who was impressed enough to take on production, and by 1975, their company was selling all the bows they could produce, over 60,000 a year. Now, 40 years later, it is hard to find any other kind of bow. Many improvements have been made, especially in the substitution of non-circular cams for Allen's pulleys, but the modern compound bow (fourth image) is still essentially Allen's invention. It is astounding what a difference it has made. A modern compound bow has a lay-off of typically 80%, meaning that if it has a draw weight of 70 pounds, it only requires 14 pounds to hold it at full draw. And the bow stores so much energy that, when released, it will propel the arrow at about 340 fps, twice as fast as a longbow. It is hard to think of another invention that has transformed its domain so radically as has Allen's compound bow.

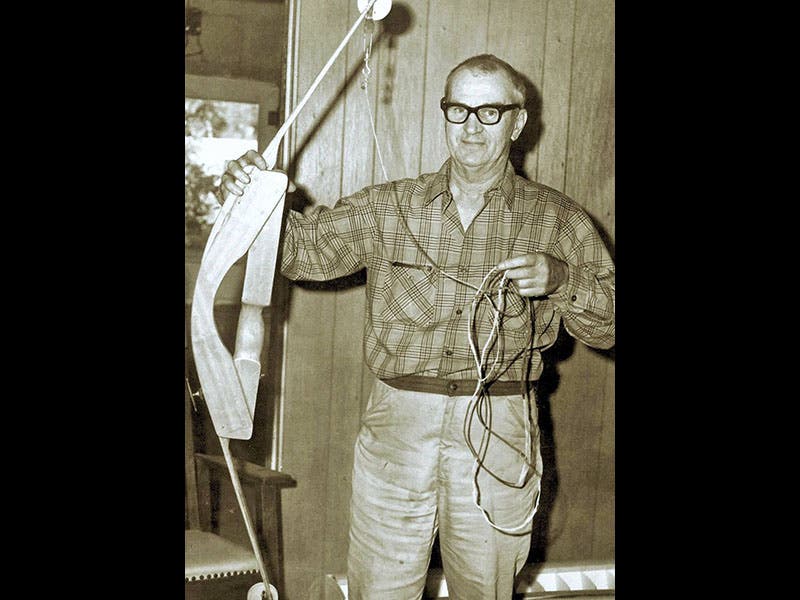

Allen lived to see the bow revolution begin (third image), but he died in a car accident in Montana in 1979, before the effect of his invention had been fully felt. He is buried right here in Kansas City, in the Floral Hills Cemetery (fifth image), and he has a place of honor in the Archery Hall of Fame in Springfield, Missouri (first image). Why Allen is not in the National Inventors Hall of Fame in Alexandria, Va., is a mystery to us all.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.