Scientist of the Day - HMS Fury

HMS Fury, a British Royal Navy vessel, was launched Apr. 4, 1814. To the best of my knowledge, we have featured a ship as Scientist of the Day only twice before: HMS Beagle, and HMS Challenger. We choose to add the Fury because it had a short but eventful life, a dramatic death, and an inspiring post-death impact that seems to make it an appropriate subject.

The Fury was what the Royal Navy called a "bomb vessel,” meaning it was broad in the beam and exceptionally sturdy, suitable for firing mortars at French fortifications or French ships (the Napoleonic wars were ongoing at the time it was commissioned). When the war ended the next year, the Navy suddenly had a surfeit of both ships and men, and so the Admiralty decided to mount an effort to find a Northwest Passage to the Pacific, and it was thought that these sturdy bomb vessels would be just the thing for bashing through the ice.

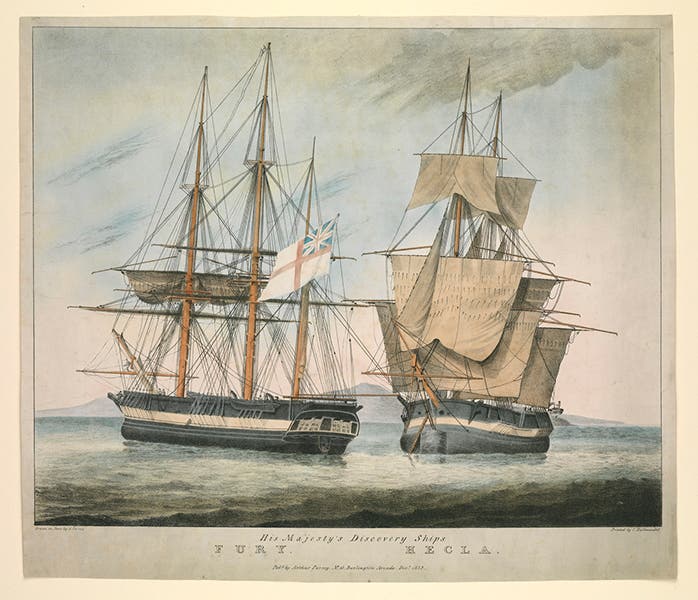

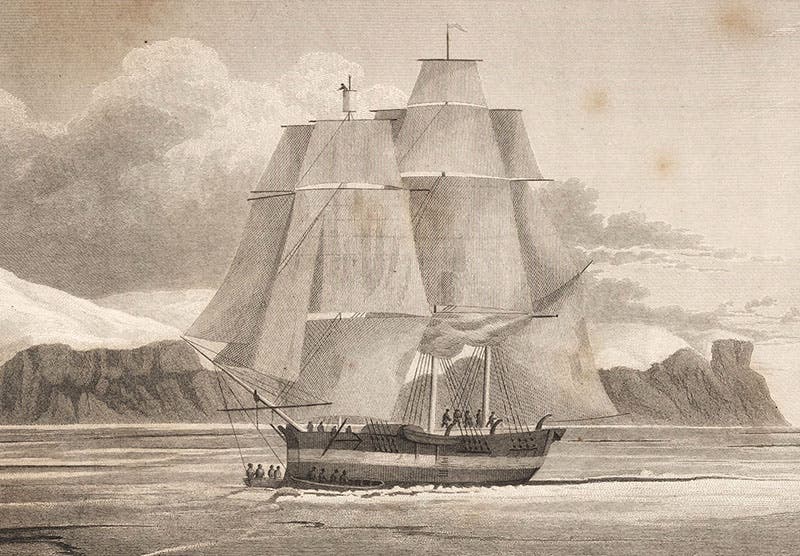

The Fury made its first Arctic venture in 1821, under the command of William Edward Parry. On his previous voyage, Parry had made it half-way across the Arctic Archipelago, and there were great hopes that the second voyage would go the rest of the way. Unfortunately, the Fury (and her companion ship the Hecla) spent two years frozen in the ice north of Hudson Bay and never made it any further, and while the voyage was an ethnological success (the crew met and recorded the activities of the Inuit who lived in the area), it certainly did not help solve the problem of the Northwest passage.

Map of Prince Edward Inlet; Fury Point and Fury Beach are at bottom left; winter quarters (Port Bowen) are at center right; zig-zag path is track of HMS Fury and Hecla through the ice, spring and summer of 1825, detail of an engraving in Journal of a Third Voyage for the Discovery of a Northwest Passage, by William Edward Parry, 1826 (Linda Hall Library)

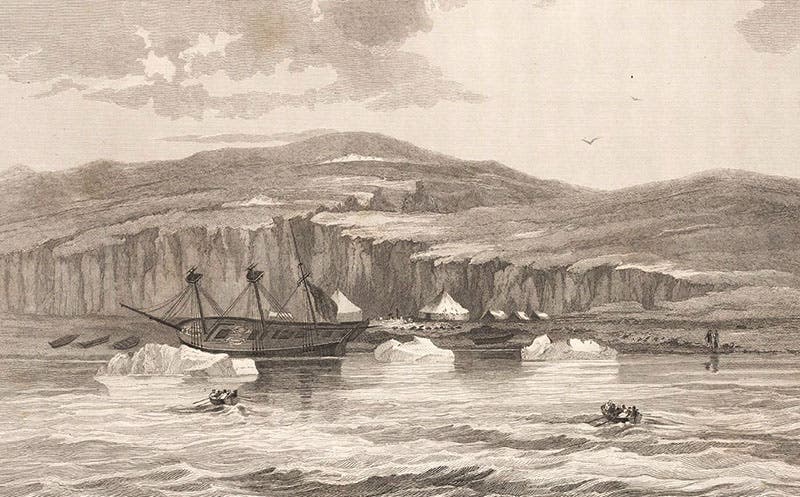

So Parry and the ships backtracked to England in 1823, and the next year Parry.and the Fury, and the Hecla tried again, this time sailing through Lancaster Sound (the route of Parry’s first voyage) and then south, down into Prince Regent Inlet, where they wintered over. For this voyage, Parry switched to the Hecla, and William Hoppner commanded the Fury. The two ships continued to explore the inlet the next spring, to see if a passage might lie in this direction. Unfortunately, Fury was caught in the ice and cast ashore on North Somerset Island (fourth image), so that it began to leak. Further south, during a storm, the Fury was cast ashore on a stony beach near a point, which they named Fury Point. Since the ship was leaking faster than the pumps could drain, and they were unsuccessful in stopping the leaks, it was decided to abandon the Fury where she lay. The stores, which included hundreds of tins of peas, pork, and veal, were all unloaded; some were taken aboard the Hecla (as well as the entire crew of the Fury), and the rest were piled up on the beach, either stacked in tents or marked with cairns, in case anyone in need of food should wander by (sixth image). The three launchboats were left as well. The date was Aug. 25, 1825; the location would become known as Fury Beach. The Hecla made it home successfully, with both crews, and Parry published an account of this, his third Arctic voyage, in 1826, from which many of our images have been taken. Most were drawn by Hoppner.

What are the odds that someone would drop in on Fury Beach for a bite to eat in succeeding years. Less astronomical than one might think. Four years later, in 1829, John Ross set off from England in his steam-powered schooner, the Victory, on a private venture to search for the Northwest Passage. They made it to the bottom of the same inlet that the Fury and Hecla had half-penetrated earlier, and Ross had high hopes of success. The Victory was frozen in the first winter, as was expected, but the Victory never thawed out, not the next summer, or the two summers thereafter. Finally, Ross was forced to abandon the ship and hike out. Sure enough, their path took them to Fury Beach, where they replenished their stores and picked up the launchboats that had been left along with the provisions. They had trouble getting out of Prince Edward Inlet in 1832, and had to spend a winter at Fury Beach, where they built a house from the debris of the Fury (seventh image). Finally, in the summer of 1833, Ross and his crew made their way up to Lancaster Sound and were rescued (amazingly) by a passing ship, which just happened to be the Isabella, Ross’s first command in 1818 (eighth image). The date was Aug 25, 1833, 8 years to the day after the Fury had been abandoned. It is likely that, without the Fury and its provisions and launchboats, no one from the Ross party would have survived.

We have the narratives of all these voyages in our History of Science Collection, and we displayed them in our 2008 exhibition, Ice: A Victorian Romance. You can see some images here of the Fury’s first voyage, showing mostly Inuit activities. Ross's narrative of the voyage of the Victory of 1829-33, where the crew was saved from starvation by the stores from the Fury, is displayed here. We also displayed Parry’s account of his third voyage, on which the Fury was lost, but both of the images there are repeated here, along with quite a few new ones.

In an interesting footnote, one of the tins of food brought back by Ross from Fury Beach, survived, unopened, until it resurfaced in the mid-20th-century. It was a tin of veal, and it was opened by researchers, to see if it was still edible. It was, in a theoretical sense, in that there were no bacteria, but no one volunteered to taste it. It was then emptied and given to the Science Museum, London, where it is on display, a tangible bit of Fury memorabilia (ninth image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.