Scientist of the Day - HMS Erebus

HMS Erebus, a bomb vessel in the British Royal Navy, was launched on June 7, 1826, at Pembroke shipyard in Wales. Bomb vessels were intended for heavy-duty mortar bombardment, so they were quite wide and sturdy, with double-thick oak hulls. Most of them had names that evoked fire and brimstone, such as Aetna, Volcano, Sulfur, Hecla, and Fury. The Erebus had a 13-inch mortar on board, which is huge, and it took quite a sturdy ship to handle the recoil from such a weapon.

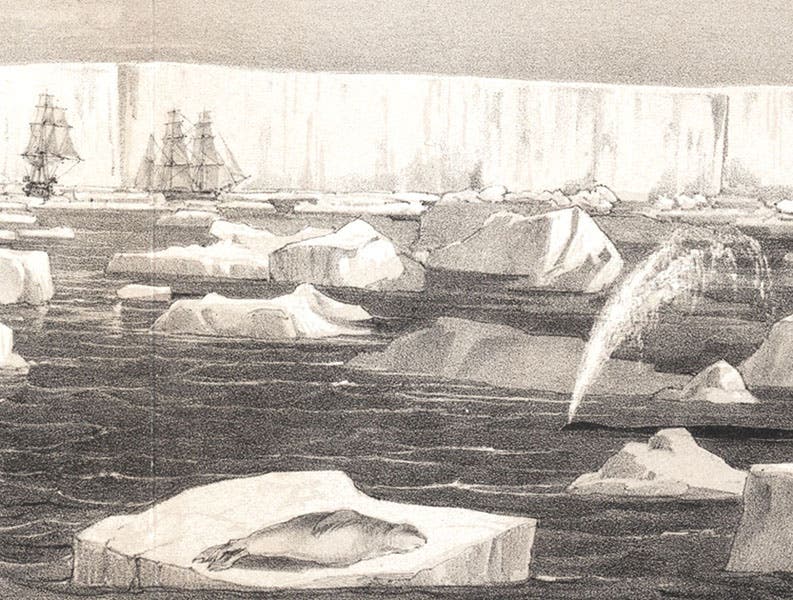

HMS Erebus (and Terror) against the Ross Ice Shelf, Antarctica, with a sun-bathing seal and a spouting whale in the foresea, detail of a folding engraved plate in A Voyage of Discovery and Research in the Southern and Antarctic Regions during the Years 1839-1843, by James Clark Ross, 1847 (Linda Hall Library)

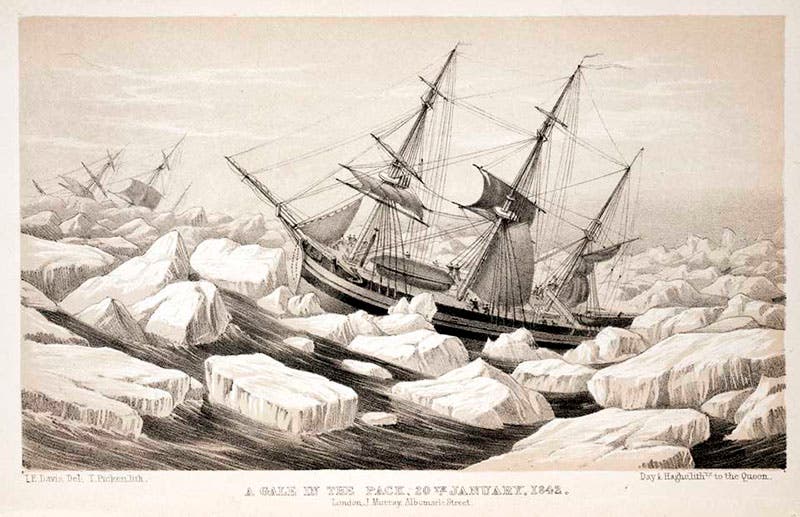

In 1818, the British began their quest to find a Northwest passage through Arctic ice, and the first ships they sent were inadequate for the job. Very quickly someone, probably John Barrow, the man behind the British Arctic onslaught, realized that bomb vessels were ideally suited for Arctic voyaging, since they were better able to withstand the crushing pressure of the ice. William Edward Parry’s successful journey across half of the Arctic archipelago in 1819-20 was in a bomb vessel, HMS Hecla. HMS Terror, another bomb vessel from the early 1800s, was one of the next to find such employment, when George Back in 1836 tried to make his way up through Repulse Bay in the Terror. It encountered more pack ice than it could handle, and barely made it back to the Ireland, but that did not stop Barrow from trying again in 1839, when he sent HMS Erebus and a refitted Terror to southern polar seas, under the command of James Clark Ross.

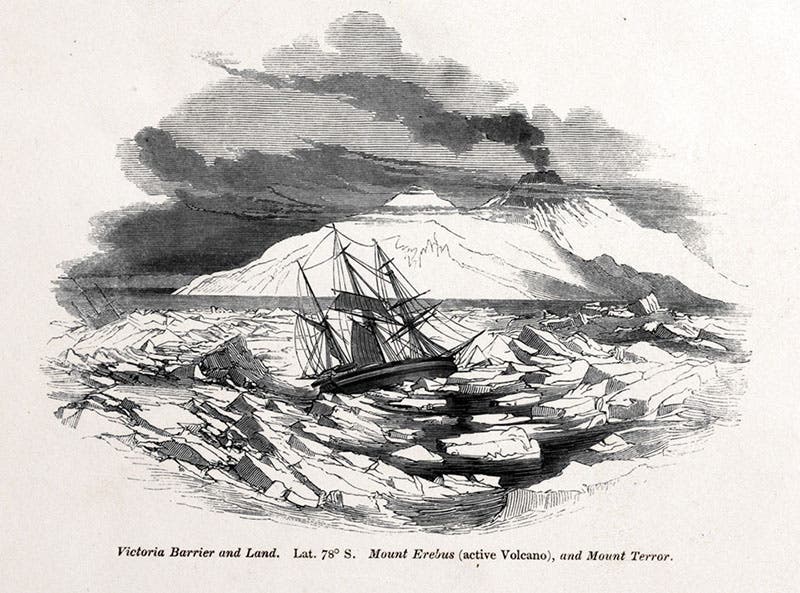

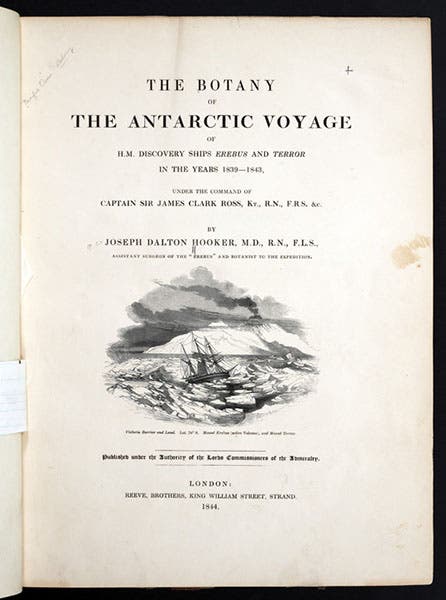

The southern voyage of the Erebus and Terror was a great success, as the crews discovered Ross Island and the Ross Ice Shelf in Antarctica (both named much later for the commander). Ross Island was of interest because it had two volcanoes, one active and the other on simmer. Ross, in a reversal of the usual procedure, named the volcanoes after the ships, with the name Mount Erebus going to the active volcano. When Joseph Hooker, the naturalist on board, later published his Botany of the Antarctic Voyage of H.M. Discovery Ships Erebus and Terror (1844), he included a title-page vignette that shows the two newly discovered volcanoes, Mount Erebus being the one belching smoke and ash (third and fourth images). One of the ships appears in the same engraving – it is hard to tell whether is HMS Erebus or Terror. Since this is a post on Erebus, we will assume it shows HMS Erebus.

After spending a year at home getting fitted for a steam engine, HMS Erebus was sent out once again on a polar voyage, again along with HMS Terror, now steam-powered as well, this time back to the Arctic, under the command of John Franklin. The mission was to find the remaining links of a Northwest Passage and sail through it. The ships left in the spring of 1845 and were last seen that summer. As best we can now reconstruct events, the ships were frozen in and abandoned in 1848 off King William Island and eventually sank. Scores of later expeditions in search of Franklin did not solve the mystery of the ships' disappearance, but the remains of the Erebus were finally found by remote divers in the fall of 2014, and a diving team in November confirmed that it is the Erebus, and bought up a ship's bell (1845 vintage), which is now on display in a museum in Gjoa Haven on King William Island. The ship is falling apart and cannot be raised, although artifacts have ben and will be removed by diving teams. The exact location is being kept secret, to forestall looters. The Terror was subsequently found in 2016. The entire area containing the two wrecks has been designated: The Wrecks of HMS Erebus and Terror National Historic Site, managed by Parks Canada and the Inuit of Nunavut.

In addition to the engravings of HMS Erebus that appeared in Ross's Voyage, the Erebus has been portrayed in two paintings now in the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich. One, which claims to show the Erebus and Terror in a Maori-populated bay in New Zealand, is so obviously not the Erebus and Terror that I won't even show it to you. The other has a closer relationship with reality, and is a view of what the Erebus might have encountered upon its return to the Arctic in 1846, before it disappeared, along with John Franklin and his entire crew (fifth image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.