Scientist of the Day - Hermann Minkowski

Hermann Minkowski, a German mathematician, was born June 22, 1864. Minkowski believed that mathematics was under-appreciated as a tool for understanding the world. In 1905, Albert Einstein, in his paper on special relativity, argued that distance is not an absolute quantity but depends on the reference system in which it is measured. Similarly, Einstein demonstrated that time is also a relative quantity and depends on its reference system. He showed that when an object moves relative to another reference system, its length shortens by a certain quantitative factor. Time slows down by the same factor.

Minkowski read this and had an idea – if time and distance behave exactly the same way in a reference system, perhaps time and distance as not as different as we intuitively think they are. Since there are three dimensions in space (three distances to measure), plus time, why can we not treat them as four coordinates in a four-dimensional geometry, with three space coordinates and one time coordinate. He called it: “space-time”.

In the geometry of space-time, time intervals might differ for different observers, and distances as well, but measurements in space-time would be invariant. Minkowski used the term “world-point” to designate an object’s place in space-time, and “world-line” to indicate its movement through space-time.

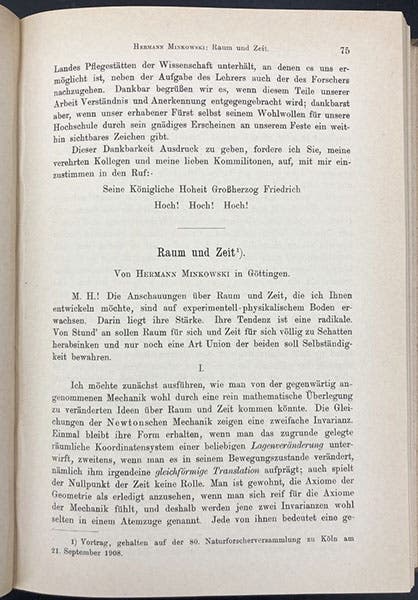

We use the terms space-time and world-line frequently (at least, science fiction authors and their readers do, and the authors of popular books on relativity), and we tend to think of them as Einsteinian concepts, but they are not. They can be traced back directly to Minkowski, and no further, and they first appear in an address given by Minkowski in 1908 in Cologne, and printed in 1909. The title is simple: “Raum und Zeit,” “Space and Time,” and the first paragraph, which you can see in German in our second image, is often quoted:

The views of space and time that I will present to you arose from the domain of experimental physics, and therein lies their strength. Their tendency is radical. From now on space by itself and time by itself will recede completely to become mere shadows and only a kind of union of the two will still stand independently on its own.

Einstein was actually highly skeptical of Minkowski's claims for the priority of geometry, and at first he wanted nothing to do with space-time, but as Einstein tried to get a handle on gravitation in his theory of general relativity (1916), he found the notion of space-time to be at first useful, and in the end essential, and he ultimately described gravity as a curvature of space-time. At the beginning of his 1916 paper, Einstein wrote:

The generalization of the theory of relativity has been facilitated considerably by Minkowski, a mathematician who was the first one to recognize the formal equivalence of space coordinates and the time coordinate, and utilized this in the construction of the theory.

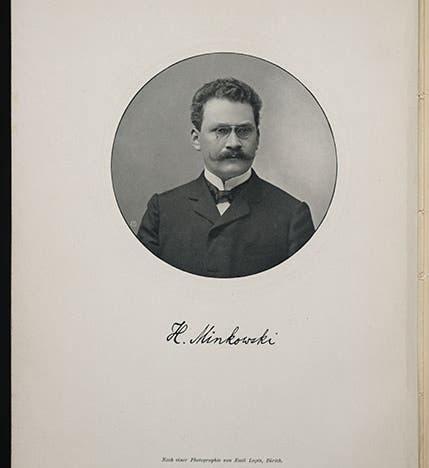

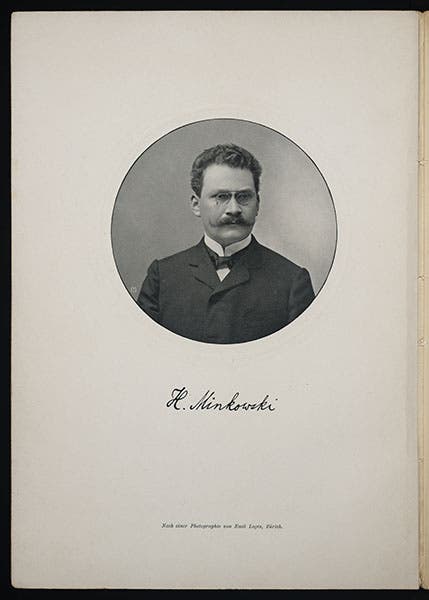

Minkowski, unfortunately, did not live to see the triumph of his space-time concept, for he died in 1909 of appendicitis, just after his “Raum und Zeit” address was printed in the Jahrsbericht (Yearbook) of the German Mathematical Society. He was just 43 years old. After absorbing the shock of his death, his colleagues rallied and published a special offprint of his address, adding a handsome photo-gravure portrait of Minkowski. We have a copy of this beautiful publication, lovingly inserted by an early owner into a custom-made folding marbled-paper slipcase, from which four of our images here were taken.

Minkowski was buried in the Heerstrasse Cemetery in Berlin, where he shares a headstone with his older brother Oskar, who was equally famous in the realm of physiology, having discovered the role of the pancreas in diabetes (sixth image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.