Scientist of the Day - Hermann Joseph Muller

Hermann Joseph Muller, an American geneticist, was born Dec. 21, 1890. Muller is best known for discovering in 1927 that X-rays cause mutations in genes, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Medicine/Physiology in 1946. But in 1921, Muller made a prediction that modern geneticists and molecular biologists, in hindsight, find remarkable. In 1917, the French scientist Félix d'Herelle had discovered a particle that kills bacteria, but which is much smaller than bacteria, and would pass through filters that could catch anything bacteria-size or larger. D'Herelle called these particles “bacteriophages” – “bacteria-eaters" – or phages for short. Others referred to them as d’Herelle particles. Muller found that the most astonishing feature of the phages was that they were capable of mutating, and passing these mutations on to the next generation.

Muller had spent many years working with fruit flies alongside Thomas Hunt Morgan at Columbia University, where it was established that genes are on chromosomes, and that gene mutations get passed along to the next generation as chromosomes replicate. Since both genes and phages can mutate and pass those mutations along by replication, Muller, speaking at a symposium in Toronto in 1921, predicted that d’Herelle substances are genes, and that if we want to learn about genes, we now have an independent route to understanding them, by experimenting on phages. In Muller’s memorable words, “perhaps we may be able to grind genes in a mortar and cook them in a beaker after all.” Considering that in 1921 no one knew anything about DNA, or even that genes are composed of DNA, and that many biologists thought that phages are just enzymes, capable of killing bacteria but with no living functions, it is amazing that Muller hit the nail right on the head. It turned out that phages are viruses that consist essentially of DNA and a protective coating, and little else. They are indeed genes on the hoof.

Muller moved in 1920 from Columbia to the University of Texas at Austin, where he did his Noble-prize winning work. An often-reproduced photo captured the “fly room” at UT-Austin in the 1920s, where Muller did his mutation experiments (first image). Muller is the one on the right, examining a jar of fruit flies with a loupe. One of the more interesting features of Muller’s fly lab is that it had a “constant-temperature” room where the fruit flies were kept, to prevent the Texas heat from sterilizing the flies. It was one of the first air-conditioned labs in the country.

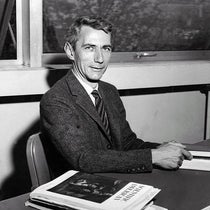

The other photos show Muller at age 32, just over a year after giving his Toronto address (second image), and in 1946, receiving his Nobel Prize in Stockholm (third image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.