Scientist of the Day - Hermann Hellriegel

Hermann Hellriegel, a German chemist, was born Oct. 21, 1831, in Mausitz. He was the son of a farmer, and he studied agricultural chemistry in school, receiving a PhD from the University of Leipzig in 1854. He was the director of several agricultural research stations in Germany for the next two decades, eventually founding a new one in Bernburg in 1882, which he presided over until his death in 1895. Bernburg is a town in Saxony-Anhalt, about 30 miles from Magdeburg, about which we once wrote a post.

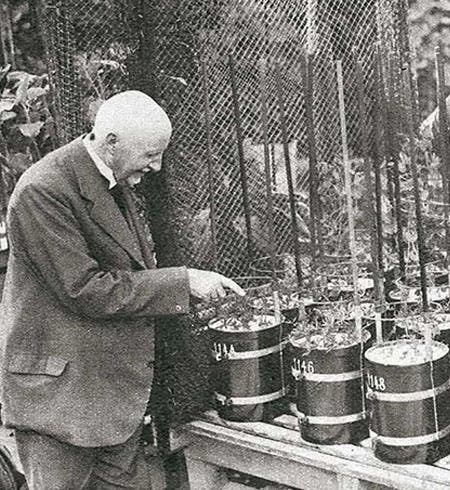

Hardly anyone outside the field of agricultural chemistry has heard of Hellriegel and his assistant, Hermann Wilfarth, but together they solved a conundrum that had perplexed farmers for thousands of years: Why do crops grow better in a field in which legumes, such as beans or clover, had previously been grown? The Romans discovered this and instituted systems of crop rotation in which the legumes played an essential role. Hellriegel had a special interest in plant nutrition, and so at Bernburg, he began in the 1880s a series of careful experiments, in which he grew legumes using what he called "sand culture," where plants were grown in tubs of sterilized sand, to which various compounds could be added at will (first image).

Hellriegel discovered that legumes, grown in sterilized sand to which unsterilized soil water was added, developed nodules on their roots, and these nodules were rich in nitrogen, in the form of ammonia salts, which the legumes somehow “fixed” from the nitrogen in the air. If one used sterilized water, the nodules did not develop, and the legumes did not produce nitrogen compounds. So there must be something in the soil water that does the trick. Hellriegel hypothesized that some kind of microbe in the soil was infecting the roots of the legumes, in response to which the plant formed nodules, like galls, and the infecting agents in the nodules had the capacity to fix nitrogen. On Sep. 20, 1886, Hellriegel reported on this discovery for the first time at the annual meeting of the Society of German Natural Scientists and Physicians in Berlin, announcing that legumes have the capacity to fix nitrogen from the air, and that the agent was some sort of micro-bacteria in the root nodules. It was a sensational announcement. Ironically, the man presiding over the session was the Englishman, Henry Gilbert, who had demonstrated conclusively in 1861 that plants could not convert free nitrogen from the air into a form usable by plants.

Hellriegel was supported in his research by the Beet-Sugar Association of Germany, and so he and Wilfarth published the results of their experiments in the Journal of the German Beet-Sugar Association, in a paper titled (in German): "Investigations into the nitrogen nutrition of the gramineae and legumes". I was pretty sure our Library would not have the journal of such a specialized group as the German Beet-Sugar Association, but I was wrong – and right. We do have that journal in our holdings. But our holdings begin in 1898, so the issue with the paper of 1888 is not present. Thus I had to read that paper (well, a small part of it) in English translation. Many of the experiments are just brilliant. My favorite involves dividing the roots of a bean plant in half and planting one half in a glass jar with sterilized soil and water, and the other in a jar with unsterilized dirt. The roots in the unsterilized soil slowly developed nodules as the leaves greened up; the rootlets in the sterilized soil developed no nodules and did not fix nitrogen. If you are not impressed (and most people who are not farmers are not), I will only note that, in 1986, the Royal Society of London, a prestigious enough group, held a two-day meeting celebrating the centennial of the feat of Hellriegel and Wilfarth, and devoted an entire issue of the Philosophical Transactions to the papers from that symposium.

The only thing Hellriegel did not discover about nitrogen fixation was the exact bacterial agent responsible for pulling nitrogen out of the air and converting it to ammonia. That discovery was made by Martinus Beijerinck about 10 years later, who identified the bacteria and named it rhizobium. He also discovered that the relationship between rhizobia and legumes is one of symbiosis; the plants cannot fix nitrogen without rhizobia, and rhizobia cannot fix nitrogen unless they are in the root nodules of legumes. Since Beijerinck, a Dutch microbiologist working in Delft, also identified the first virus (in 1898), and invented the name virus, I would say he deserves a post of his own in the near future.

Hellriegel is quite a hero to agricultural chemists in general, and especially to those of German persuasion. After his death in 1895, a monument, topped by a bronze portrait bust of Hellriegel, was immediately erected in Bernburg (1897). During World War II, the bronze bust was melted down for its metal, but someone wisely made a plaster cast of the bust first. Immediately after the war, Bernburg city authorities hauled out the plaster copy, had it recast in bronze, and it was back in place by 1948, and may still be seen today (fourth image). It would be nice to find a closeup photo of the bust, for it would undoubtedly provide a more appealing likeness than the one austere portrait photograph we have (second image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Using an astrolabe to measure the depth of a well, woodcut in Elucidatio fabricae vsusq[ue] astrolabii, by Johannes Stöffler, 1513 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/a998eb50-55d2-4a88-ace2-a50aa5fa86e7/Stoffler%201.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)