Scientist of the Day - Herman Kahn

Herman Kahn, an American futurist, was born Feb. 15, 1922. Kahn was the best known of a new breed of analysts that came to the forefront in the late 1950s – those trying to grapple with the threat of nuclear war. Kahn worked for the Rand Corporation, and later founded the Hudson Institute. In 1960, he published a book called On Thermonuclear War, followed two years later by Thinking about the Unthinkable (1962). In the first book, Kahn proposed the idea of a Doomsday Machine, a stay-at-home nuclear weapon that, since it did not have to be delivered, could be made immensely large and totally destructive. If set to go off automatically at the advent of a nuclear attack, and if programmed to do so regardless of human intervention, such a Doomsday Device would serve as the ultimate deterrent, because no one would dare start a nuclear war, since the result would be the destruction of the entire planet. Film-maker Stanley Kubrick read On Thermonuclear War, realized that the military strategy expressed there was totally insane, and set out to make a movie lampooning the policy of what was then called "mutually assured destruction." The result was Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964).

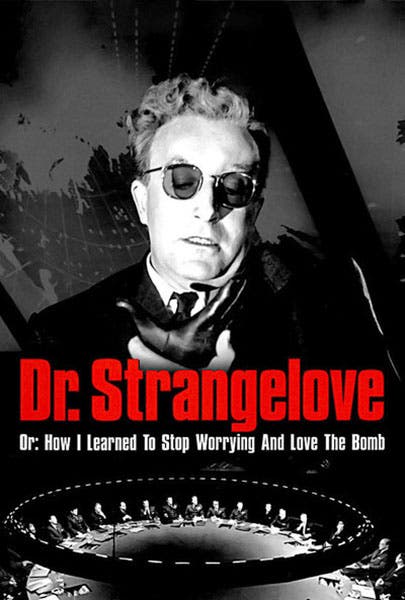

I am sure many of you have all seen the film, and if not, you should do so, as it is one of the sharpest black comedies ever put on film. You can read a short summary at our post on the anniversary of the release of the film (Jan. 29, 1964), or here is the briefest of backstories: a rogue American General has launched a bevy of B-52s towards Russia, telling them that the U.S. has been attacked, and since they cannot be recalled, the U.S. President, played by Peter Sellers, has given the Russians the flight plans of the planes so they can be shot down. One plane, however, has made it through and threatens to drop its payload. At this point the Russian ambassador reveals that the Russians have a Doomsday Machine. The President is thunderstruck and calls on Dr. Strangelove, his science adviser (and an ex-Nazi) to explain how such a device works and why anyone would build such a thing. Strangelove (who appears for the first time in this scene, and who is also played by Sellers) proceeds to do so. This 4-minute clip from the film captures the entire scene, and the best part comes in the last ten seconds, when Strangelove says, “Yes, but the whole point of the Doomsday Machine is lost… if you keep it a secret! Vy didn’t you tell the world, eh?” Notice the reference in the scene to the “Bland Corporation.”

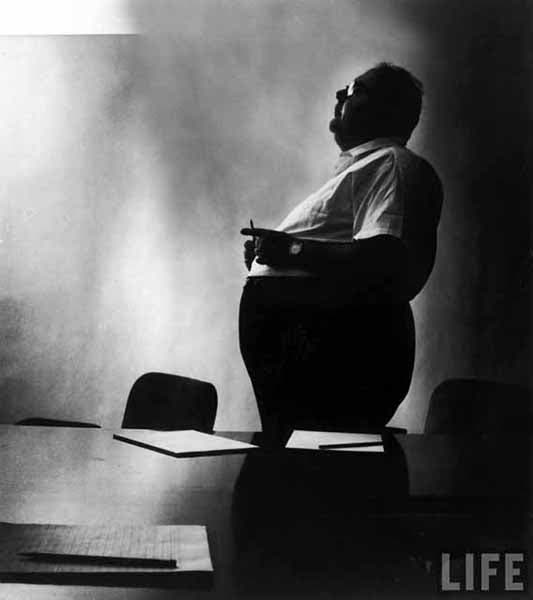

It is sometimes suggested that Kahn, in addition to supplying Kubrick with the idea of the Doomsday Machine, was also the model for Dr. Strangelove. This is patently not the case, as a photograph of Kahn makes clear (third image). Kahn was larger than Sellers the President, Sellers the Group Captain, and Sellers the Strangelove, all put together. It seems rather that the character of Strangelove was fashioned from a variety of personae, most notably Werner von Braun, father of the U.S. rocket program and an ex-German, and Edward Teller, father of the hydrogen bomb, and of Hungarian birth. But many of Strangelove’s attributes, including the famous Nazi muscle-memory salute, and his occasional reference to the President as “Mein Führer,” sprang from the manic mind of Peter Sellers.

It is often forgotten that Kahn did not advocate a Doomsday Machine; he merely considered its possibility as a deferent, and then rejected it. He thought it was important to consider all the future implications of the nuclear arms race, and this at a time when many people, perhaps most people, thought it was improper to speak publicly about the threat of nuclear holocaust. So, in bringing the subject out into the open in 1960, he performed an important public service.

In 1967, Kahn (with Anthony Weiner) attempted to predict some of the developments that would shape The Year 2000, as his book was called. He was right about the rise of Japan and South Korea as world economic powers, and correctly predicted the development of extremely high-strength structural materials. He did not do as well when he foresaw that long-range weather forecasting would get much better, and although he predicted portable phones, he never envisioned the smart phone.

Kahn died, unexpectedly, in 1983, at the age of 61. His vision has been missed.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.