Scientist of the Day - Herman Boerhaave

Herman Boerhaave, a Dutch physician, chemist, and botanist, died Sep. 23, 1738, at the age of 69. His father intended Herman for the clergy, and he gave it a go, but after his father's death, he found that his real interest was in medicine. He found a teaching position in Leiden, and must have impressed the rectors, for when he was invited to move to Groningen, he was told he would be offered the first medical chair that came open. While he waited, Boerhaave published two medical textbooks which became extremely popular.

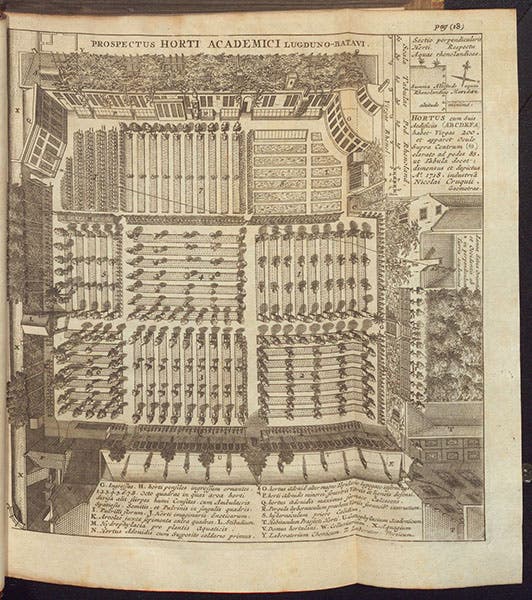

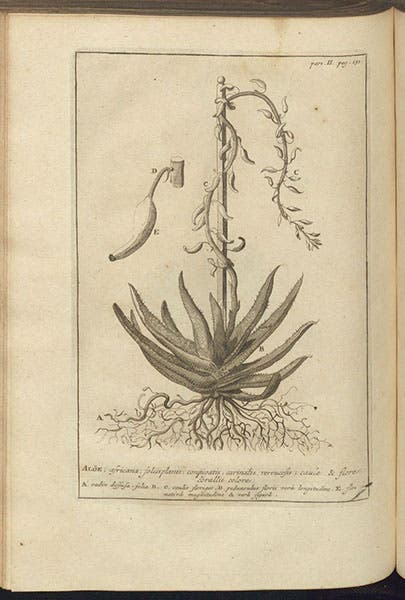

Sure enough, in 1709, the professorship of medical botany became available, and Boerhaave was offered the position. The fact that he had no special training in botany was not an obstacle, as it seldom was in those days. And who's to criticize? Within a short time, Boerhaave was as knowledge as anyone about medical plants. The botanical garden at Leiden, the oldest in northern Europe, had been languishing, and Boerhaave soon put it straight, building the plant stock back up, until it had over 5000 species of plants. This was in the decades before Carl Linnaeus worked out his system of botanical nomenclature in Uppsala, so the classification and naming of plants was still chaotic, but Boerhaave managed. In 1710, he published an Index plantarum to the plants in the garden. By 1720 he had introduced so many new specimens that a second edition was called for, which he called Index alter plantarum. We have a 1727 printing of the expanded version. The book does not have many illustrations – it is clear that plant description was primarily a verbal art at the time – but it does have an engraving every 30 pages or so, some of them quite nice (fourth image) – and there is also a plan of the revitalized Leiden Garden, which we show as well (second image).

Boerhaave's main responsibility was the education of medical students. I do not know how much he used the botanical garden for teaching – probably a lot, as Linnaeus would do shortly. But in other areas, we know that Boerhaave’s teaching methods were innovative. He was one of the first physicians anywhere to use the "clinical method," where students were taught from a patient's bedside. In fact, Boerhaave had a special teaching ward set up at the hospital, with six beds for male patients and 6 for females, where instructive cases could be housed for the benefit of students. Since Boerhaave taught so many students over the years – several thousand went on to become physicians and medical professors themselves – he is often described as the father of the clinical method in academic medicine.

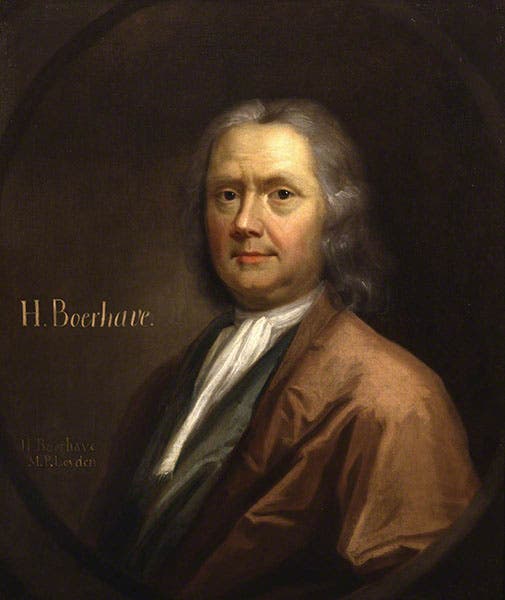

In 1718, Boerhaave also took on the chair of medical chemistry when it became vacant, meaning he now had three chairs at the Leiden medical school. He had been teaching chemistry for some years, since chemistry was a large part of pharmacy by the 18th century, but he never considered himself a chemist. However, the medical students seeem to have liked that, for they could understand what Boerhaave was saying, and they kept detailed notes. In 1724, Boerhaave was surprised – and outraged – to discover that a publisher had issued a textbook on chemistry, under Boerhaave's name, but without permission, indeed, without Boerhaave's involvement in any way, and he apparently was unable to gain any satisfaction in the courts. He got so disgusted that he gave up his chair in chemistry in 1729.

However, friends persuaded him to write his own chemical textbook, correcting all the errors that were to be found in the pirated edition, and Boerhaave did so. Elementa chemiae was published in 1732 in 2 volumes, and it was soon in demand everywhere and translated into all the major languages, including English. Peter Shaw, an English physician, had translated Boerhaave’s pirated textbook into English in 1727, which should have put him in Boerhaave's doghouse. But when it came time for a new edition of his translation, he decided, to his credit, that he should translate the new version – the official version – and he did so. We have a 1753 edition of this translation, which is called: A New Method of Chemistry … Translated from the Original Latin of Dr. Boerhaave’s Elementa Chemiae, as Published by Himself, where the title makes clear that this is translated from the edition that Boerhaave actually wrote himself. We show the title page of Shaw’s edition of 1753 (fifth image) as well as a passage from Boerhaave’s “To the reader”,where he laments the agony he went through with the unauthorized edition of 1724 (sixth image).

Detail of first page of “The Author to the Reader,” where Boerhaave laments the unauthorized 1724 edition of his chemical textbook, in A New Method of Chemistry … Translated from the Original Latin of Dr. Boerhaave’s Elementa Chemiae, as Published by Himself … by Peter Shaw, 3rd ed., 1753 (Linda Hall Library)

Boerhaave is a rarity among well-known historical figures in the history of science – someone known primarily as a teacher. Except for the clinical method, he never really discovered anything new, medical or chemical. He just taught those, like Albrecht van Haller, who did. And he apparently did so superbly. It is a pleasure to honor someone whose principal achievement was teaching, and teaching well.

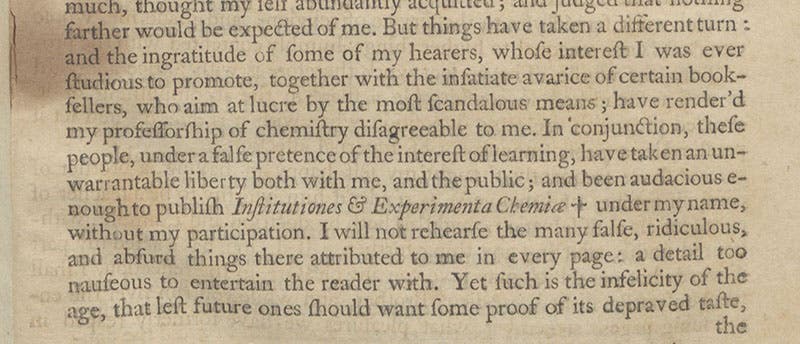

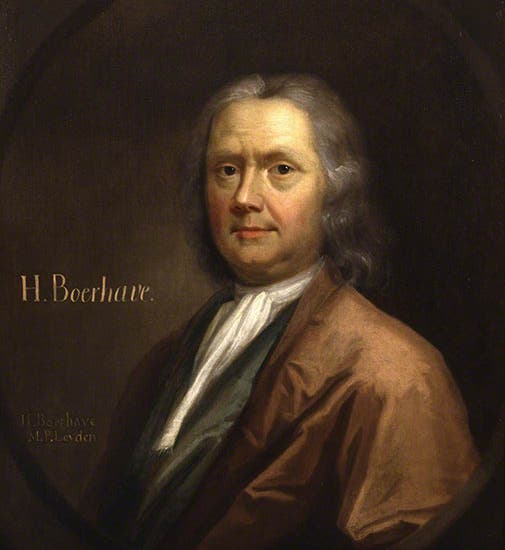

There are many 18th-century engraved portraits of Boerhaave, mostly in posthumous editions and translation of his works, but not too many oils. I really like the oil portrait in the Royal College of Physicians in London, which was apparently made from one of the engravings, in a reversal of the usual practice (first image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Using an astrolabe to measure the depth of a well, woodcut in Elucidatio fabricae vsusq[ue] astrolabii, by Johannes Stöffler, 1513 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/a998eb50-55d2-4a88-ace2-a50aa5fa86e7/Stoffler%201.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)