Scientist of the Day - Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer, an English sociologist, was born Apr. 27, 1820. Spencer became an evolutionist in the 1840s, just after Darwin had done so, but his evolutionary ideas came from Lamarck, not Darwin. In the 1850s, he began trying to apply the idea of evolution to sociology and ethics, and over the next forty years he produced a number of volumes that collectively came to be called "The Synthetic Philosophy," an attempt at a unification of all the sciences on evolutionary principles. After the publication of Darwin's Origin of Species in 1859, Spencer was invited by Thomas H. Huxley, Darwin’s “bulldog,” to join a new organization known as the "X Club," whose purpose was to defend Darwinism and further the cause of science free from the restraints of organized religion. It was just after he joined the X Club that Spencer coined the expression "survival of the fittest" as an easier-to-grasp term than natural selection, and it has been popular ever since. Other members of the X Club included Darwin’s good friend, Joseph Hooker (who gave us the rhododendron), the young anthropologist John Lubbock (who gave us the terms Paleolithic and Neolithic), and the physicist John Tyndall (who gave us the Greenhouse Effect). The X Club met regularly for dinner for 30 years, but since they never admitted any new members, the Club eventually died out as the members died off.

Spencer was well-enough respected in England, although he was never considered a great thinker by his friends. But Spencer developed a great following in the United States in the 1870s and 1880s, and the movement known as "Social Darwinism" that grew up in the U.S. was largely an outgrowth of Spencer's ideas (little of Darwin's theory was in evidence, so it would have been more accurate to call it "Social Spencerism"). Spencer was regarded as one of the great minds in history by many Americans of this period. Others were not so impressed. Huxley once said that Spencer's idea of a tragedy is a theory killed by a fact (although, to be fair, he said it in Spencer's presence, and Spencer was supposedly quite amused). Josiah Royce, the American philosopher, less good-naturedly commented that Spencer's idea of a unification of science was to find a bag big enough to contain all the facts. Apparently the acquisition librarians of the Engineering Societies Libraries in New York concurred with Royce, for they bought very few Spencer works, and thus bequeathed very few to us, just late editions of First Principles and Principles of Biology. If you wish to study Spencer, I am afraid you will have to go somewhere else.

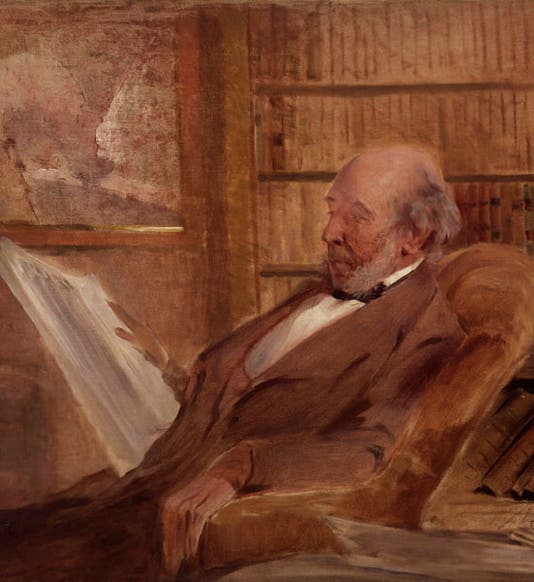

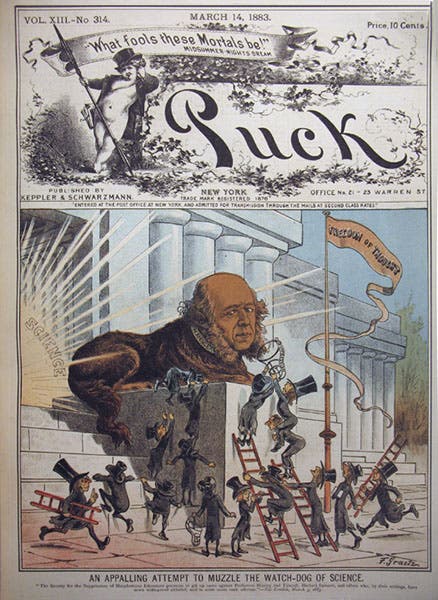

There is an attractive portrait of Spencer (by John McClure Hamilton, 1895) in the National Portrait Gallery (first image), and a not so attractive caricature in Vanity Fair in 1870 (second image), and there are lots of surviving photographs, but I could not find a single bust or statue of Spencer anywhere. This may be in part because Spencer was entirely self-educated, so there was no Oxford or Cambridge college from his past to claim him and provide him with a bust, nor was he later associated with any institution that also might have done so. The closest I could come to a statue was a caricature on the cover of Puck magazine, the American satirical journal that rivaled the English Punch and Vanity Fair in its partiality for caricature. The illustration from the Mar. 14, 1883 issue shows a statue of a dog with Spencer's face, guarding the edifice of “Science”, with a group of zealots attempting to muzzle him (third image, just above) The caption says: "An appalling Attempt to Muzzle the Watchdog of Science" and the sub-caption goes on: "'The Society for the Suppression of Blasphemous Literature proposes to get up cases against Huxley and Tyndall, Herbert Spencer and others who, by their writings have sown widespread unbelief and, in some cases rank atheism."

Spencer was buried in the East Cemetery of Highgate in London, a cemetery that tolerated agnostics and freethinkers and that also functions as a nature preserve, which seems to be a wonderful idea (fourth image, above). Spencer is interred not too far from his good friends George Eliot (Marian Evans) and her common-law husband George Henry Lewes (fifth image, below).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.