Scientist of the Day - Herbert McLean Evans

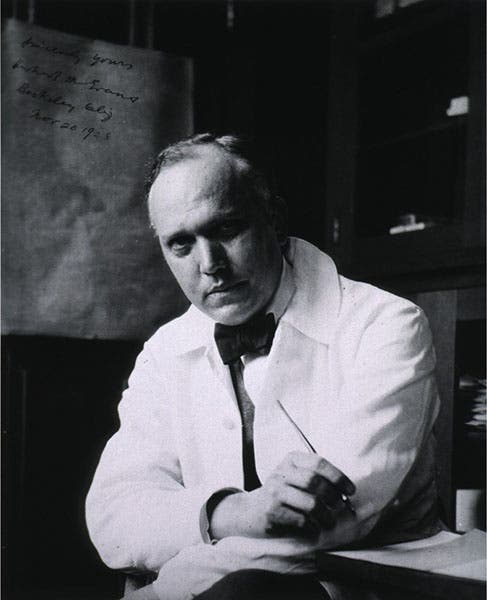

Herbert McLean Evans, an American research physician and anatomist, was born Sep. 23, 1882, in Modesto, California. Evans attended the University of California at Berkeley as an undergraduate, and then moved on to Johns Hopkins for his medical degree. He became interested in human embryonic development and human growth, quickly established a reputation in the field, and in 1915, he was invited to join the department of anatomy at the University of California in 1915, which had moved to Berkeley from San Francisco after the great earthquake of 1906. Evans would remain there for the rest of his career, moving back to San Francisco when the medical school returned in the 1950s. He made many important discoveries, such as vitamin E (a co-discovery), and human growth hormone. Colleagues considered him a viable candidate for a Nobel prize, but such nominations were unsuccessful.

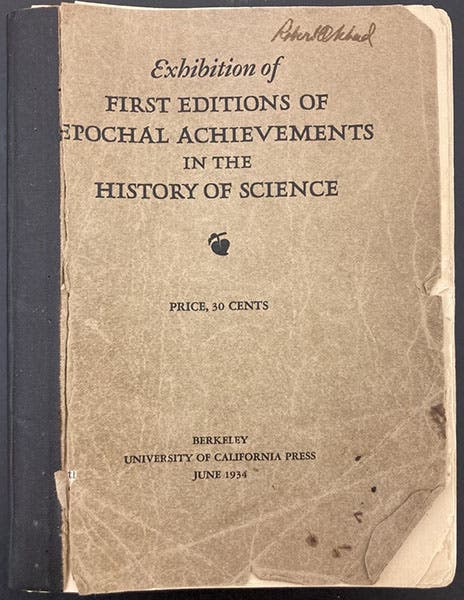

But today, we focus on Herbert M. Evans, history of science book collector. Perhaps because of his liberal arts education at Berkeley, Evan had a keen interest in both books and the history of science and medicine. As soon as he could afford to do so, he started collecting what would later be termed the "Milestones of Science," those books, such as William Harvey's De motu cordis (1628) and Isaac Newton’s Principia (1687), that transformed their disciplines. In 1934, Evans mounted an exhibition of his collection at Berkeley, with a printed catalog, a pamphlet that inspired many later collectors, such as Harrison Horblit and Bern Dibner, to make similar collections. It also inspired our former Librarian, Joseph Shipman, because our copy is thoroughly annotated, noting books we have, and books we need. We will have to get this scanned so that you can see an acquisitions librarian at work.

Wikipedia states that the Evans collection went to the University of Texas at Austin. Well, one of his collections ended up there. But Evans amassed seven separate milestone collections over the years. According to Jacob Zeitlin, an eminent rare book dealer in the sciences, Evans spent so much money on books that he repeatedly went broke, and had to sell off his books. He would swear off collecting each time, but as soon as the check came in, he was off on another book-buying tour. One collection went to the University of Chicago, another to Samuel Barchas, a collector himself, and another to the University of Utah. Several sales were brokered by dealers, such as Zeitlin, and then sold individually through catalogs, so nearly every history of science collection in the country has some books that came from one Evans' Library or another. We are no exception.

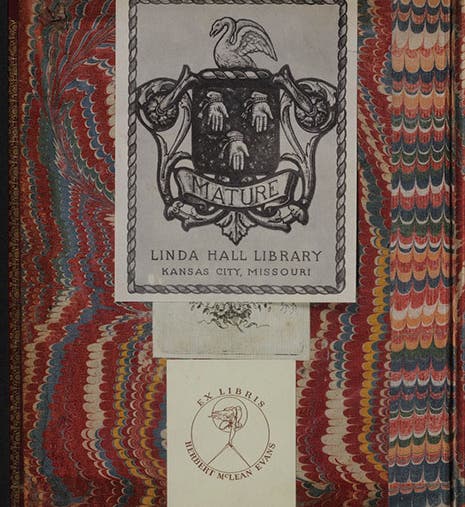

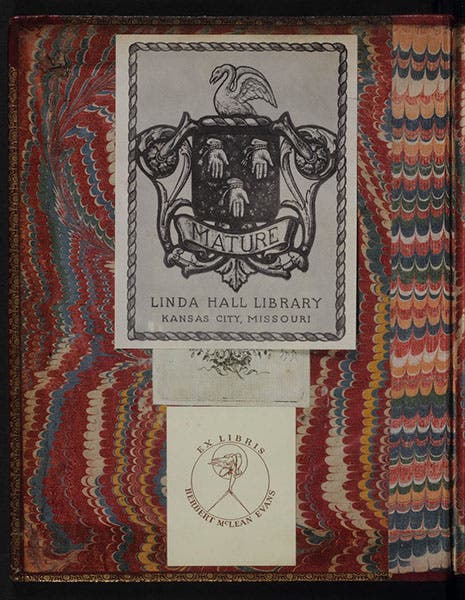

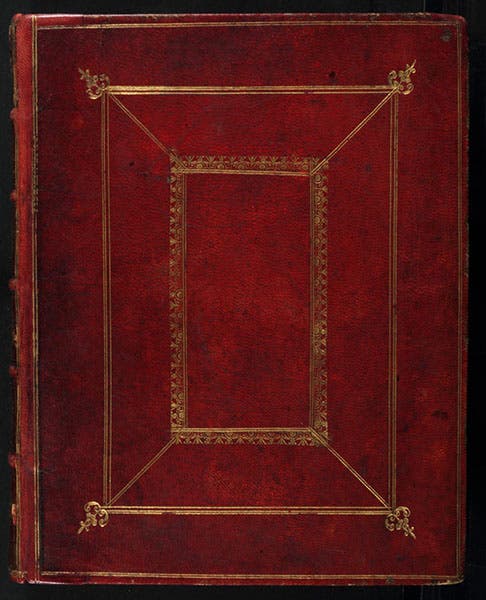

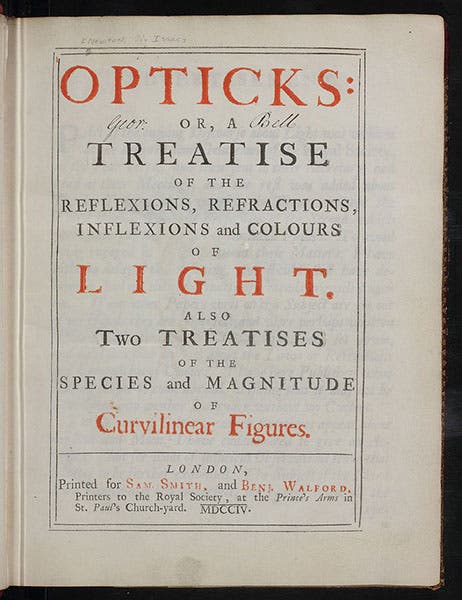

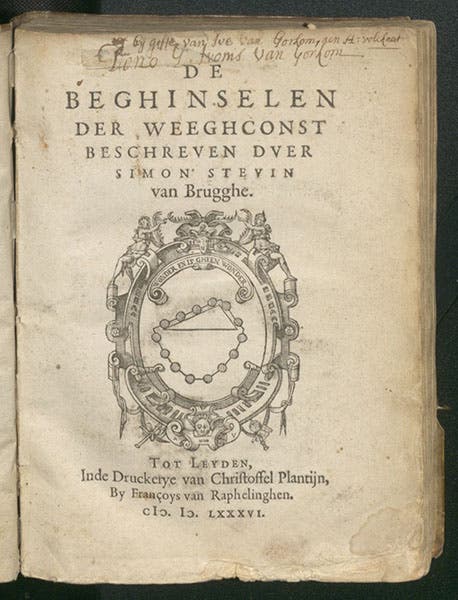

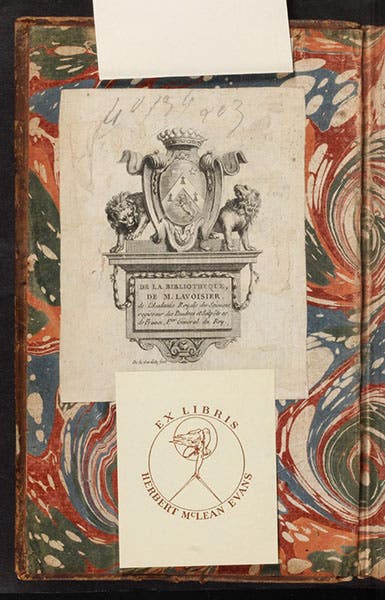

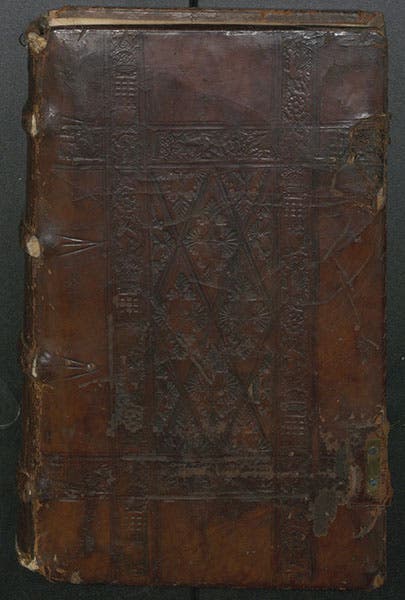

We have at least nine books in our special collections that carry Evans' elegant bookplate, some of them truly milestone works, such as Rene Descartes' Discourse on Method (1637), Isaac Newton's Opticks (1704), Simon Stevin's Dutch book on hydrostatics (1586), and Otto Brunfels herbal (1530). These are lovely copies with fine bindings, as you can see in several of our photos (third, sixth, and ninth images) ��– Evans had excellent taste in books.

The custom among rare book librarians, when they acquire a book and put in place their library's bookplate, is to never permanently cover up an older bookplate, as that would obscure the provenance of a book. Since our old bookplate was large and Evans' was small, the Evans bookplate is often hidden underneath ours at first glance. But our bookplate will be attached only at the top, so it can be lifted up to see the bookplate (or bookplates) beneath. Several of our Evans' books have three bookplates, the third being the owner before Evans and us. We show you the inside front cover of the Evans copy of Rudolf Erich Raspe's Specimen (1763), where the original owner was Antoine Lavoisier (eighth image).

Seven of our Evans books have been scanned and are now part of our digital collections. On several occasions, the scanner was canny enough to look under our bookplate on the inside front cover (what bibliophiles call the front paste-down) to see if another bookplate lay underneath, and if so, to take an additional scan with our bookplate folded out of the way. Such is the case with our copy of Brunfels Herbarum (ninth, tenth, and eleventh images). But it is easy to miss the fact that our bookplate is covering another. So if you look at our scan of Descartes’ Discourse on Method, (which you can do here), you would never know that this was an Evans book without consulting the catalog record.

Now that I am Evans-inspired, I intend to slowly check the bookplates in our milestone books, and in the books we bought from Jacob Zeitlin in the 1950s and 1960s (there were many). If I can find just one sleeping Evans bookplate, I will be happy.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.