Scientist of the Day - Henry Smeathman

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Henry Smeathman, an English insect collector, was born Feb. 9, 1742. In 1771, he convinced a consortium of patrons in London to sponsor him on an insect-collecting trip to West Africa--these included Joseph Banks, just back from Captain Cook's first voyage; Dru Drury, a wealthy insect collector; and John Fothergill, a Quaker physician. What Drury wanted most was a goliath beetle, since William Hunter had one, and he didn't. Drury decided Smeathman was a good choice, and off Henry went, arriving in Sierra Leone in 1771.

Smeathman was a clever man. First of all, he managed to stay alive, whereas most Europeans who visited West Africa succumbed to malaria within months. He then gradually assimilated himself into the European-African trading network, essential for doing business in Africa. He even married the daughter of the native king of the island on which he spent much of his time, which allowed him access to many traders along the coast, and when his first wife died, he married the daughter of another king. He spent four years in West Africa and sent back thousands of insect specimens to Drury, who parceled them out to the other sponsors. One of these was indeed a goliath beetle, the second ever to enter England, which Drury kept for himself (sixth image). Smeathman came home by way of a slave-ship to the Caribbean, which cost him another four years, so it wasn't until 1781 that the world learned what else Smeathman had been doing in West Africa. He had been studying termites.

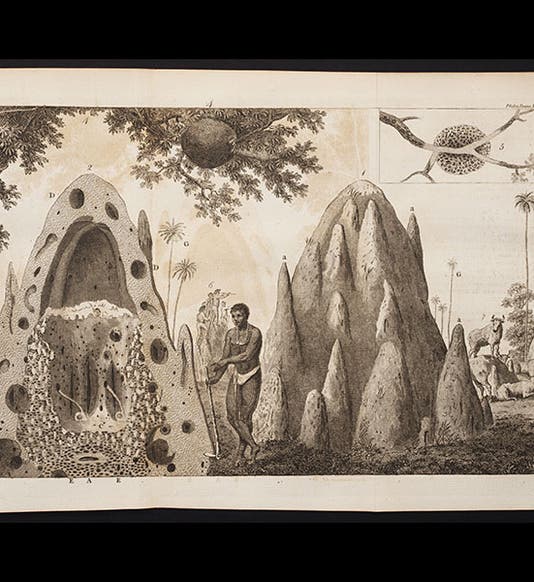

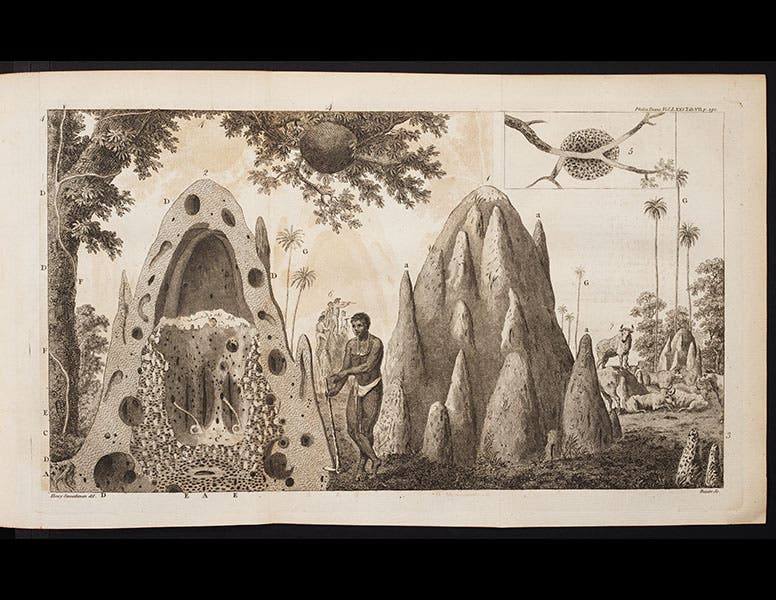

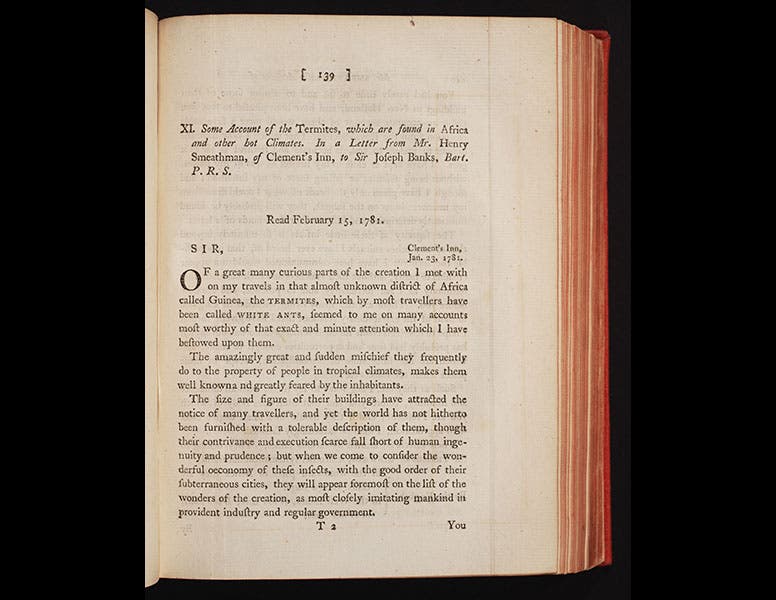

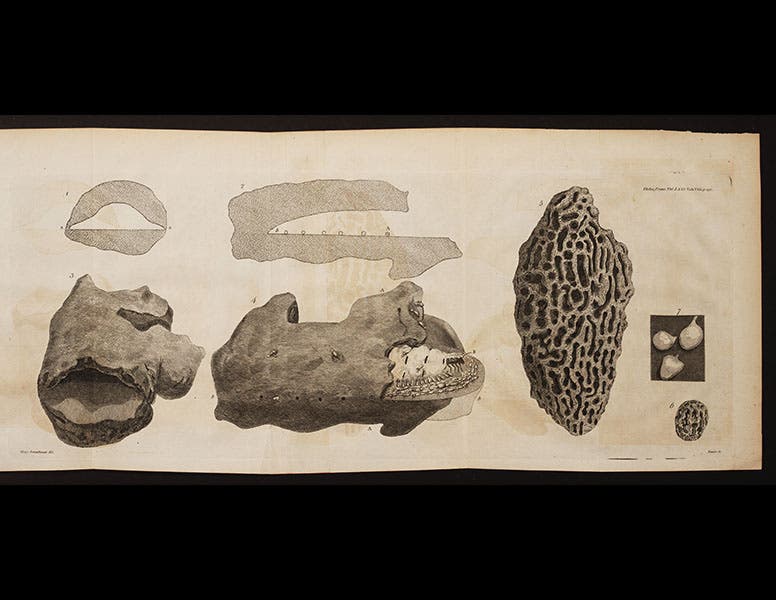

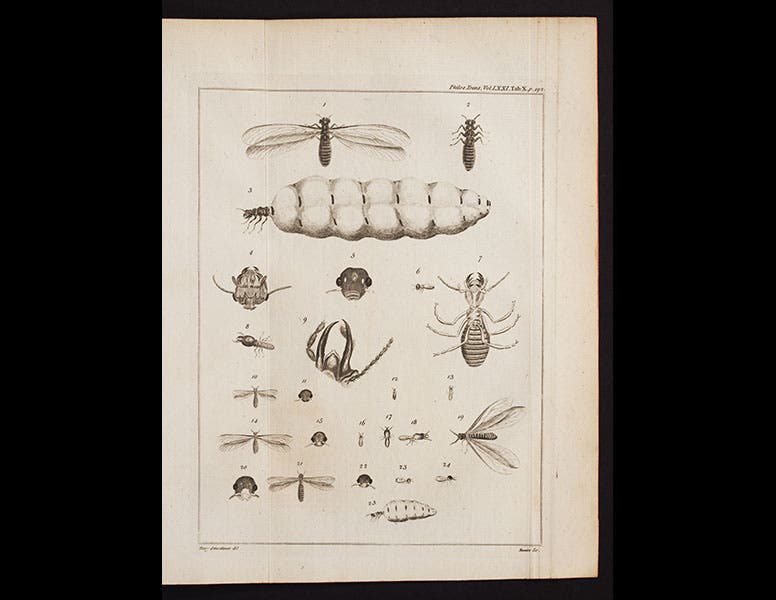

On Jan. 23, 1781, Smeathman wrote a long letter to Banks, "Some Account of the Termites which are found in Africa, and other hot Climates," accompanied by his own paintings. The letter was read to the Royal Society of London in February and then published that year in the Philosophical Transactions of the Society, along with four engravings made from his watercolors (second image). This is an amazing article, the first time any European had studied the giant earthen structures built by African termites. Smeathman grouped the world’s termites into five species, applying the Linnaean system for the first time to termites: Termes bellicosus, destructor, mordax, atrox, and arborum (four of these are fairly fierce terms--mordax = biting, atrox = cruel, only arborum is fairly neutral). It was the bellicosus “warlike” termite of West Africa that especially attracted Smeathman’s attention. This was the kind that built impregnable packed-earth mounds over 12 feet tall, using techniques similar to that employed on the original Qin dynasty Great Wall of China. One of the engravings shows a section of a termitarium, revealing not only the network of pathways, but the locations of the fungus gardens, the nurseries, and the royal chamber for the Queen (first image). The other plates depict the different castes of termites: workers, soldiers, king and queen; as well as details of the queen’s chamber, and views of other kinds of termite mounds. We reproduce the four engravings above.

Smeathman’s termite paper was really an anomaly in his career. What he most wanted to do was return to Sierra Leone and set up plantations such as were found in the Caribbean, with the exception that his colonial plan would not require or allow slave labor. His model for the ideal colonial society? A termite colony, with its operational harmony and clear division of labor. Unfortunately, his past bouts with malaria caught up with him before he could put any of his plantation schemes into motion, and he died of a fever in 1786, at the age of 44.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.