Scientist of the Day - Henry More

Henry More, a British philosopher, died Sep. 1, 1687, at the age of 72. Not to be confused with the sculptor Henry Moore (with two "o's"), our Henry More was one of the celebrated "Cambridge Platonists" who flourished in mid-17th-century England and did their best to reconcile Plato with Christianity and the mechanical philosophy that was beginning to make inroads into British natural philosophy. When he was young, in the 1640s, More became enamored with Descartes and his proposal that all physical phenomena were the result of matter in motion. By the mid-1660s, Moore was giving up on Descartes, whom he found too mechanical. Moore had decided that without some sort of immaterial essence in control, there would be no room for God in a mechanical universe. He advocated the existence of a "Spirit of Nature" that controlled the universe of matter and was responsible for bringing order out of chaos. He became embroiled with Robert Boyle, who thought he could explain the workings of a vacuum pump perfectly well without calling on any guiding Spirit, and with Robert Hooke, who was completely baffled by an immaterial Spirit that obeyed no rules and could do whatever it wanted, and the nature of which we could not, by definition, ever comprehend.

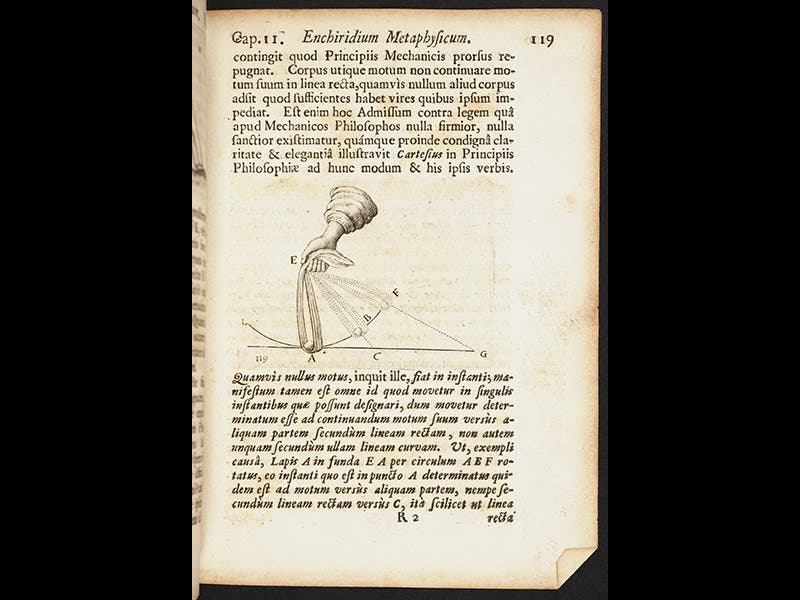

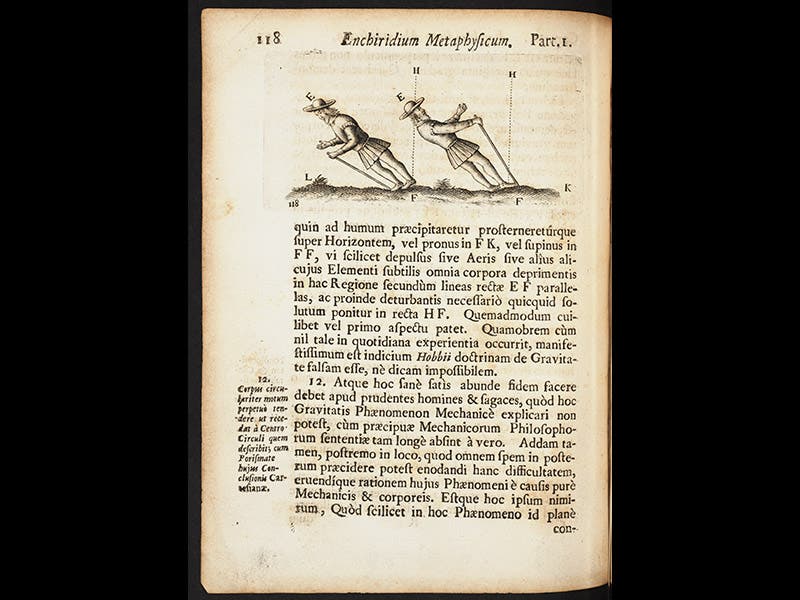

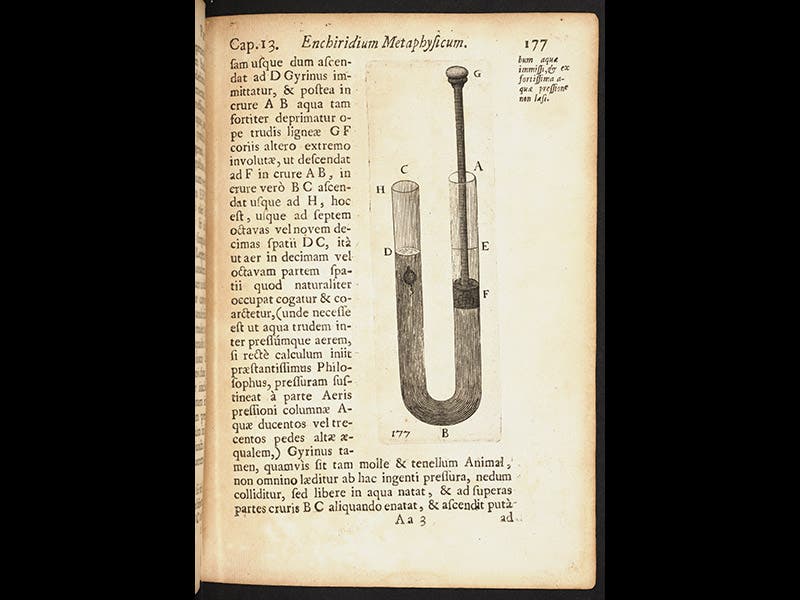

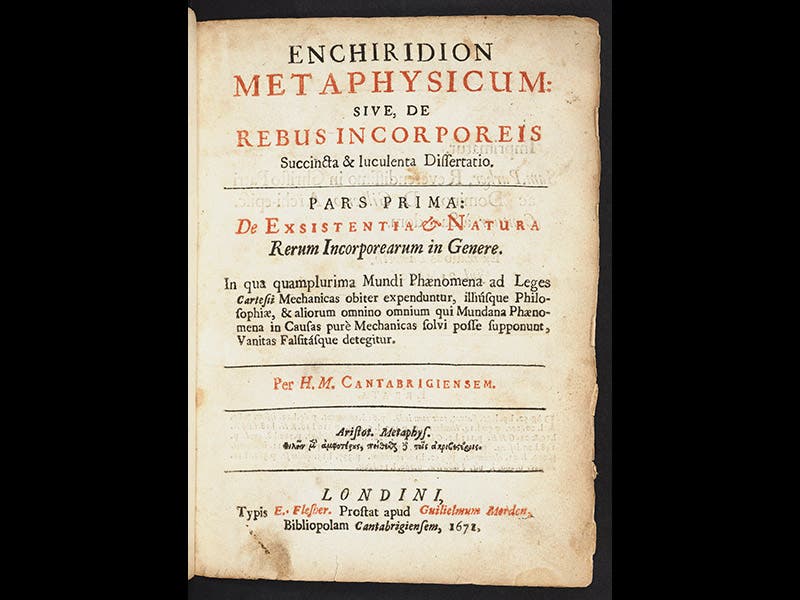

In 1671, More published his Enchiridion metaphysicum, in which he took on Descartes, Boyle, Hooke, and numerous others and put forward his case for a Spirit of Nature. We have More's Enchiridion in our History of Science Collection, and visually, it is a curious book. It has many woodcut text illustrations, similar to those in Descartes' Principia philosophiae (1644). In fact, many of More's images are copied straight out of Descartes, such as the drawing of a sling in action, which Descartes used to demonstrate rectilinear inertia (second image). But other illustrations are quite novel, such as the line-up of men who are demonstrating a physical principle that we cannot guess (first image), or the teetering figures at considerable odds with gravity (third image). Descartes' use of images has been well analyzed by historians, but so far as we know, no one has tackled the woodcuts of Henry More's Enchiridion. Perhaps some reader, intrigued by the images above, will respond to the challenge.

There are no busts or statues of More that we know of, not even at his home institution of Christ's College, Cambridge, and very few portraits. An engraved portrait was included as a frontispiece to his Works (1679), and that is the one that we show above.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.