Scientist of the Day - Henry Lucas

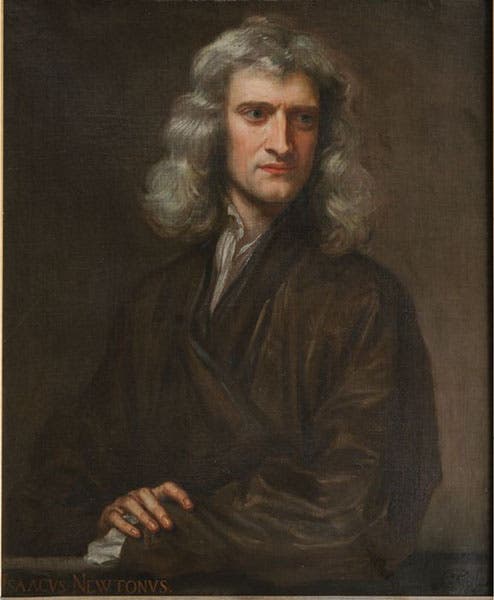

On Jan. 18, 1664, King Charles II of England officially established the Lucasian Chair of Mathematics at Cambridge University. Henry Lucas, member of Parliament from Cambridge (1640-48), of whom we have no portrait, died on July 6, 1663 (so family tradition has the date), and he left his library of 4000 books to Trinity College, Cambridge, and also bequeathed land to the university that yielded £100 per annum to fund a professorship of mathematics. We don't know enough about Lucas to know why he specified mathematics for his newly inaugurated chair. But the bequest was accepted, and in 1664, Isaac Barrow (first image) was appointed as the first Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at Cambridge. We have 5 books by Barrow in our collections, as well as his Opera and two recent biographies.

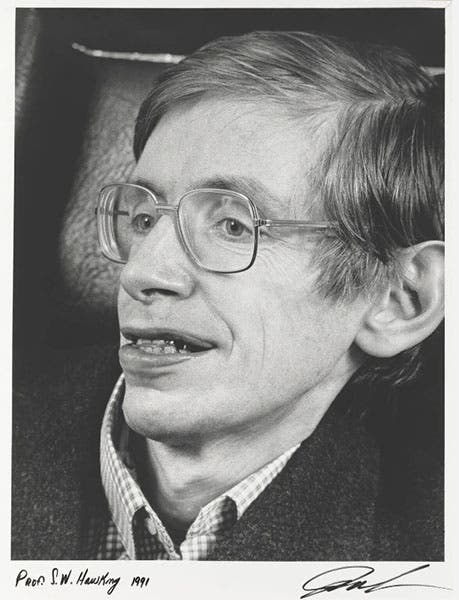

Sometime after his appointment, Barrow acquired a master’s student of considerable promise, Isaac Newton. In 1669, Barrow resigned his chair, probably because it did not pay very well, and he wanted to pursue a clerical career. Newton was appointed to succeed him (second image). It is often said that Barrow resigned because he recognized Newton as a superior mathematician, but there is no evidence of that. Newton had just performed his experiments on light (including his experimentum crucis) and had discovered the rudiments of calculus (this while away from Cambridge during the plague year of 1666), and he was certainly a good choice. He may have accepted the position because Lucas had stipulated that the occupant of his chair should not be an active member of the Anglican Church, and Newton could have used this as an excuse not to take holy orders (which indeed he never did).

It was Lucas' good fortune that Newton was the second occupant of the Lucasian Chair, otherwise Lucas would hardly be remembered today. Newton did nothing to distinguish the chair by his teaching – he had few students, and in some years, no students at all. But he added luster to the chair by his publications – his Principia (1687), and Opticks (1704) and much more. He resigned the professorship in 1702 so that he might move to London, where he was already Master of the Mint, and soon to become President of the Royal Society.

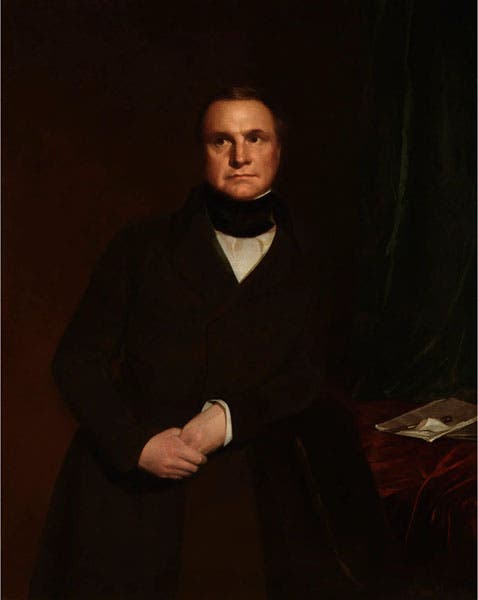

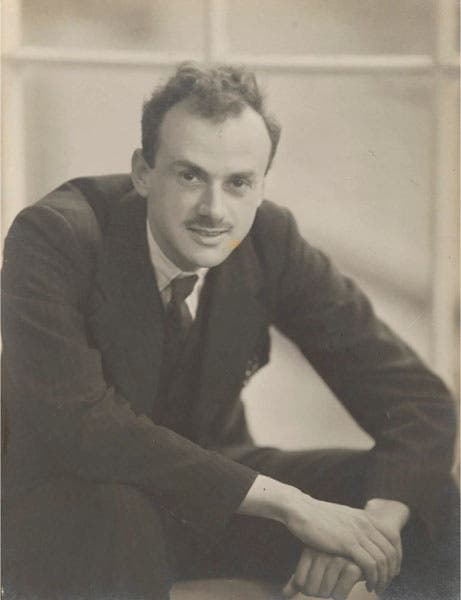

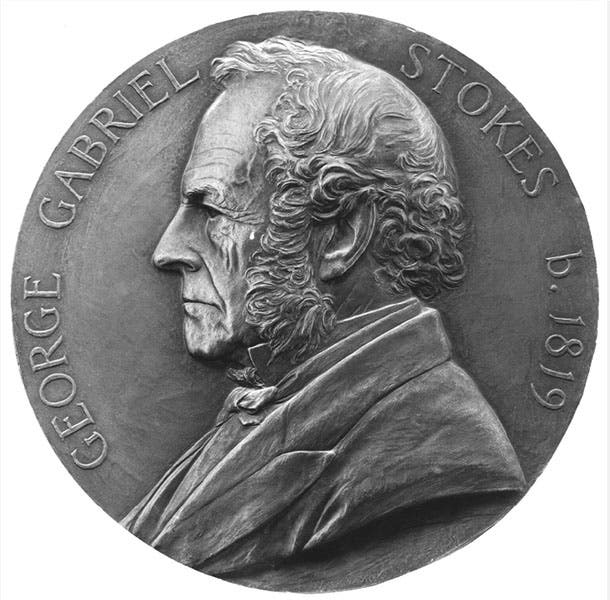

The Lucasian Chair has had 19 occupants so far. Newton is just barely the most famous – the antepenultimate occupant was Stephen Hawking, the most acclaimed mathematical physicist of the 20th century, who held the Lucasian Professorship for 30 years, 1979-2009 (third image). There were many notables in between, including George Babbage (1828-39), inventor of the modern mechanical calculating machine (fourth image), and Paul Dirac (1932-1969), who brought relativity into quantum mechanics and predicted the existence of anti-matter (fifth image). George Stokes (1848-1903) had the longest tenure in the chair, 53 years, during which he established most of what we know about fluid motion, viscosity, and drag (sixth image).

There have been a few duds, as one might expect – George Woodhouse had brought Leibnizian calculus notation to England in 1803, which was notable, but his tenure as Lucasian Chair (1820-22) was not only undistinguished, but brief, as he resigned when he found out how little it paid. His successor, Thomas Turton, kept the chair for only four years (1822-26), before he resigned to pursue, like Isaac Barrow, more divine matters. But most of the others, such as Nicholas Saunderson (1711-39) and Michael Green (2009-2015) were cream of the crop and helped maintain the distinction of the Lucasian Chair as the most prestigious endowed chair in the world.

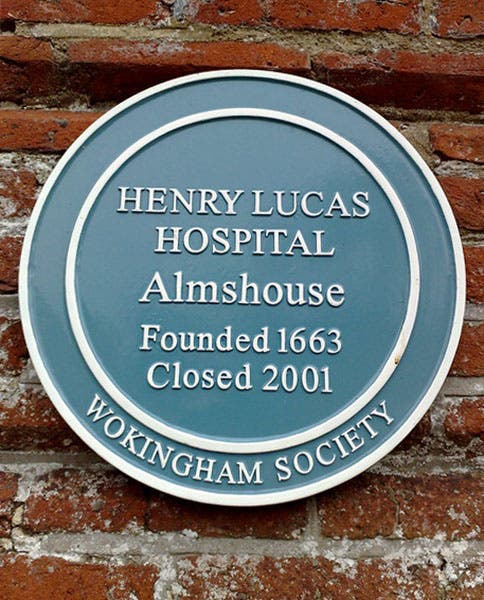

It is seldom remembered that Henry Lucas left an even larger sum of money, £7000, to build and support an almshouse (hospital) for senior citizens of Berkshire and Surrey. The Lucas Hospital was built in 1666 in Wokingham and served the community for 335 years until it was closed in 2001, passing its history of social service on to the Henry Lucas Cottages at Whiteley Village in Surrey. It might be argued that the almshouse bequest has yielded much more social good over the years than the more famous Lucasian Chair. We see here both the Hospital (which still stands) and its commemorative blue plaque (seventh and eighth images).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.