Scientist of the Day - Henry Englefield

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Henry Charles Englefield, an English antiquarian, died Mar. 21, 1822, at the age of about 69; his date of birth is unknown. Englefield was wealthy, and a dilettante of sorts (we are not passing judgment here--Englefield was a dues-paying member of the Society of Dilettanti, founded in London in the 1740s to foster interest in the art and antiquities of Italy). Englefield, a Catholic, was particularly interested in British churches, especially those that had been Catholic and were forced into ruinhood by the Dissolution of the Monasteries that began in 1536. The last two decades of the 18th century marked the beginnings of British romanticism and its fascination with ruins of all kinds (such as Tintern Abbey), and Englefield, although no artist, felt a great kinship to those who swooned in the presence of an ancient and lost world.

Englefield visited the Isle of Wight off the southern coast of England around 1800 and began an extensive series of notes on the local antiquities, which he wanted to publish. So far it doesn't sound as if he had much to do with science. But he did. For Englefield was unusual in believing that there was no sharp dividing line between antiquarianism and geology. Both disciplines studied the distant past, using objects and artifacts as their source material rather than the written word, and they played by very much the same set of rules, and with the same goal--to reconstruct a long-lost age from prehistoric materials.

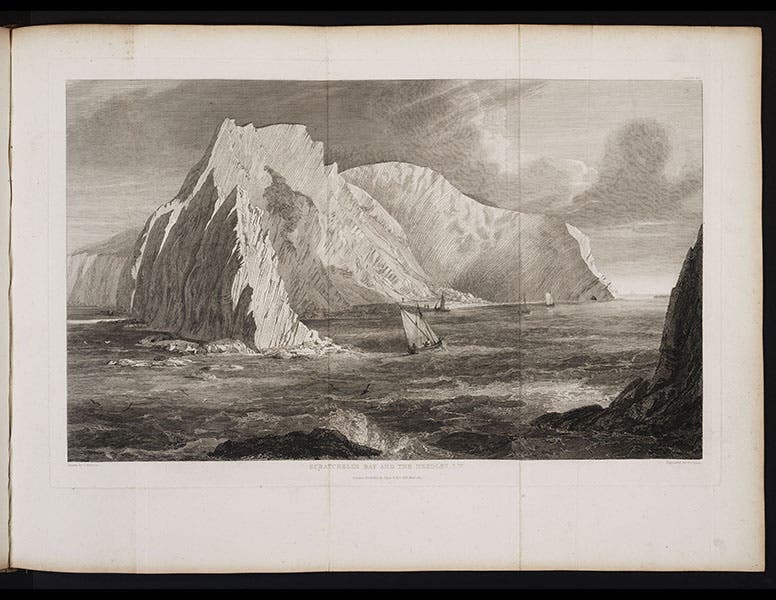

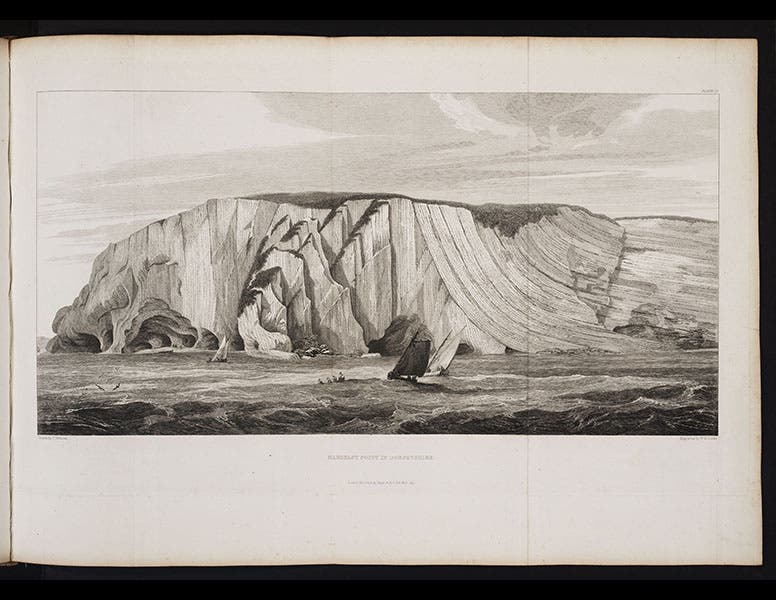

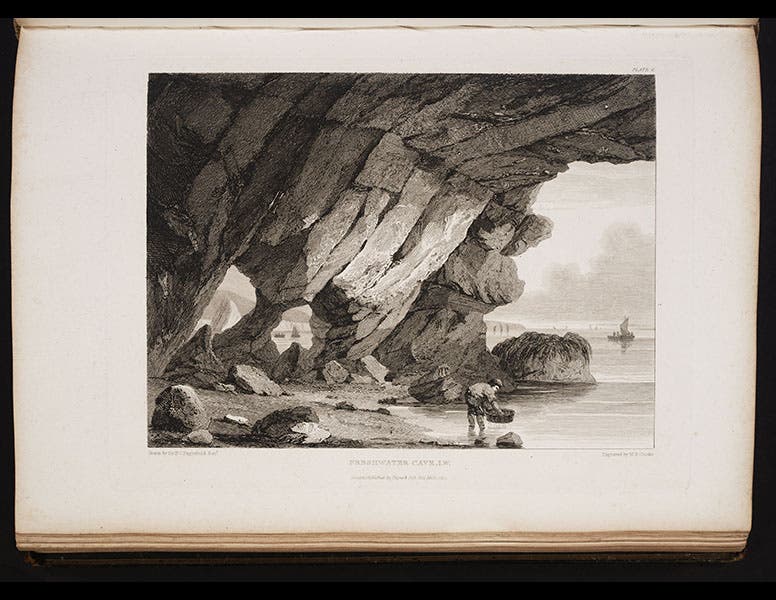

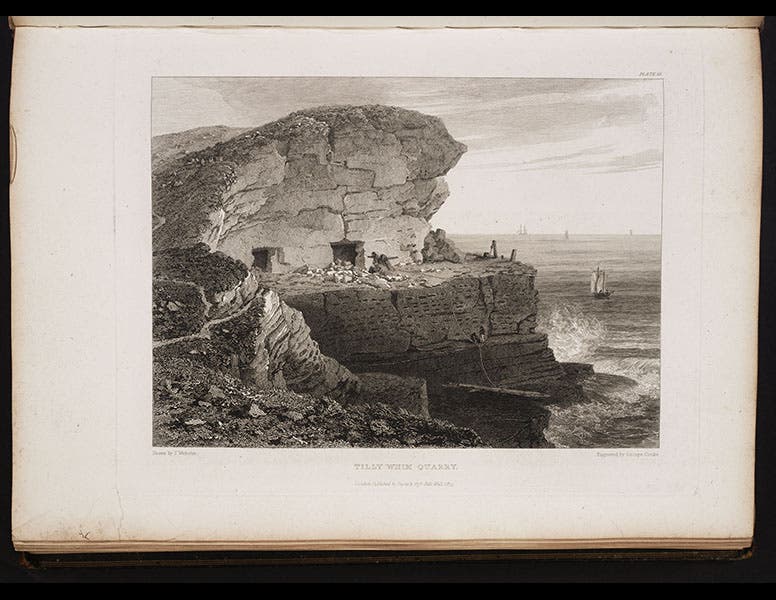

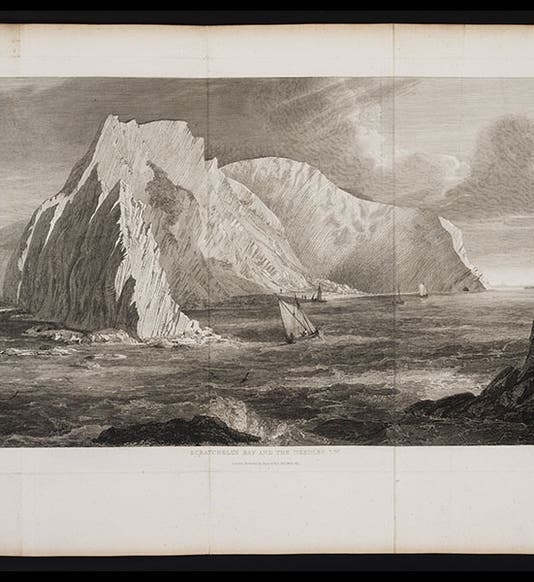

Although Englefield was perfectly competent to write about the antiquities of the Isle of Wight, he did not feel that he had sufficient expertise to deal with the very interesting but complex geology of the island, so he brought in an expert geologist as a collaborator: Thomas Webster. Webster was an early member of the Geological Society of London (founded in 1807) and a talented draughtsman; Englefield was fortunate to find him and convince him to be his illustrator. The result of their collaboration was A Description of the Principal Picturesque Beauties, Antiquities, and Geological Phaenomena of the Isle of Wight (1816). This is a large and beautiful quarto, with illustrations, mostly by Webster, of just what the title suggests: scenery, ruins, antiquities, and geological strata. The book cost 10 guineas in 1816, which was a huge sum for a book in those days--only the dilettanti would have been able to afford it. We are pleased to have a copy in our History of Science Collection, and all of the illustrations above are from this book. They show, in order: Scratchell's Bay and the Needles; Handfast Point (in Dorset); a detail of three colored coastal views; Freshwater Cave; Tilly Whim Quarry; and a detail of a folding map of the Isle of Wight and the Dorsetshire coast. The portrait of Englefield, by Thomas Phillips, is in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Using an astrolabe to measure the depth of a well, woodcut in Elucidatio fabricae vsusq[ue] astrolabii, by Johannes Stöffler, 1513 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/a998eb50-55d2-4a88-ace2-a50aa5fa86e7/Stoffler%201.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)