Scientist of the Day - Harry McNish

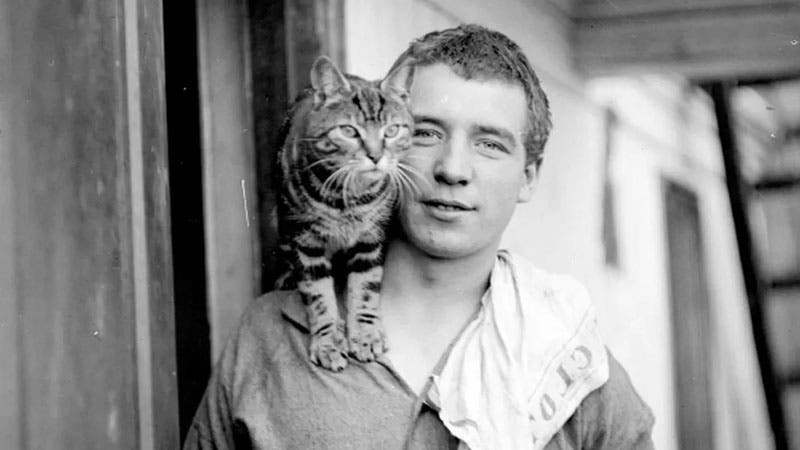

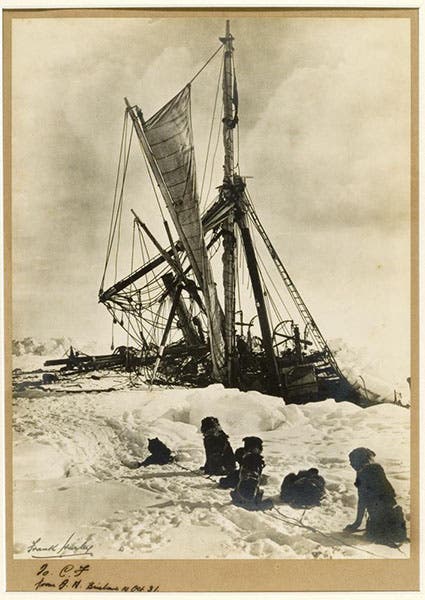

Harry McNish, a Scottish ship's carpenter, was born Sept. 11, 1874, in Port Glasgow, Scotland. McNish (sometimes spelled McNeish) was chosen by Ernest Shackleton to be the carpenter aboard the Endurance on the British Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914-16. Shackleton planned to steam down to the Weddell Sea of Antarctica, below South American and South Georgia Island, and then trek across Antarctica all the way to the Ross Sea on the other side (this was shortly after Roald Amundsen had successfully reached the South Pole in December 1911, and returned safely, and Robert Scott had also reached the South Pole, a month later, but died on the return). Other than build on-deck kennels for the scores of sled dogs brought by Shackleton, McNish did not have too much to do, carpentry-wise, although he did amuse the crew with his pet cat, Mrs Chippy, who was a favorite with the men (Chippy was a standard nickname for a ship's carpenter, so "Chippy" McNish's pet naturally became Mrs. Chippy, even though it was soon discovered that Mrs. Chippy was a tomcat). We include here a photo of Mrs. Chippy with one of the crew (third image). Antarctic life was fine until the Endurance got frozen into the icepack early in 1915 and never worked her way loose. The ship was gradually squeezed into kindling and sank on Nov. 21, 1915 (fourth image).

McNish offered to built a new ship from lumber and nails salvaged from the wreckage, but Shackleton preferred to use the three existing longboats, dragging them over the ice to open water. McNish did not like this idea and said so – he was older and more experienced than all the crew except Shackleton, and he was not shy about expressing his mind in his thick Scottish brogue. At one point he even refused to take his place in the towing harness; although he soon resumed his duties, his open rebellion did not sit well with Shackleton. And relations between the two men did not improve when Shackleton ordered that all the animals that could not take care of themselves – four pups and Mrs. Chippy – had to be shot. I am not sure McNish ever got over that.

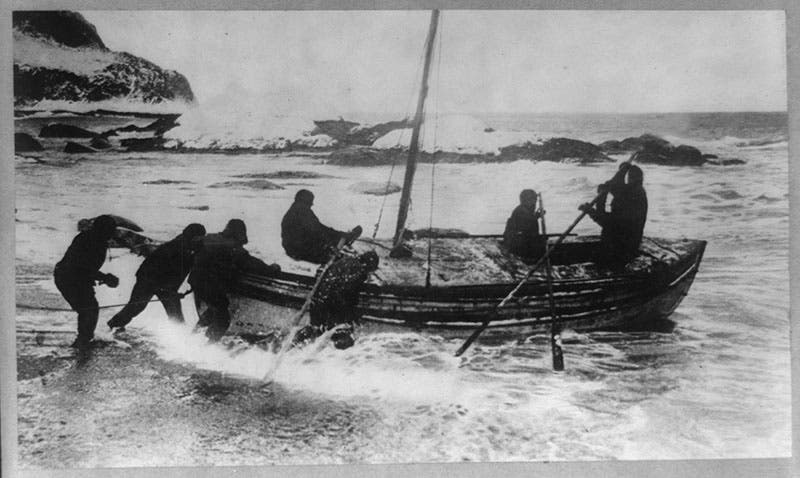

Nevertheless, after the crew (28 men plus Shackleton) made it to open waters and across it to desolate Elephant Island, McNish showed his value to the expedition. Shackleton decided to take a small contingent of five men and attempt to sail to South Georgia Island, over 800 miles away across a perpetually stormy sea. Two of the small boats stayed on Elephant Island, inverted and turned into shelters, while the third, the James Caird, was modified to manage an ocean voyage through 50-foot waves. It was McNish who did all this work, raising the gunwales and strengthening the ribs and the keel, and building an onboard shelter, under conditions when most of us would not even have been able to pick up a nail with our frozen fingers. And McNish was one of the 5 chosen to crew the vessel on its voyage. It is not clear why Shackleton chose McNish for his crew – some think he was reluctant to leave the complaining McNish on the island, afraid he would poison the morale of the men left behind. We include here a photo of the launch of the strengthened James Caird (first image), taken by expedition photographer Frank Hurley, with his pocket Kodak camera (he had to abandon his heavy glass-plate camera when they began their over-ice hauling of the lifeboats)

As most people know, the voyage of the James Caird was a success; they reached the south shore of South Georgia Island after 16 days of the worst seas imaginable. Shackleton and two men then made it across the mountain range that separated the south coast from the north, where the whaling stations were – a range that had never been crossed by humans – and then managed to corral a ship and get back to Elephant Island to pick up the rest of the crew. Not a life was lost. And there is no doubt that they couldn't have done it without the carpentry wizardry of McNish. Yet when time came for Shackleton to recommend recipients for the Polar Medal, he recommended the entire crew except for four: three trawlermen, and McNish. The omission of McNish was thought to be a grave injustice by most of the crew – many said so, some in writing, one even suggesting that of the entire crew, McNish was the most deserving of a medal. The denial of McNish’s achievements was not one of Shackleton’s greatest moments.

After his return from Antarctica, McNish worked at a few jobs in the merchant navy. His physical condition slowly worsened, because of the hardships of the Endurance experience, and he ended up in New Zealand, where he worked until he could work no longer, and then lived on handouts and slept on the docks, until his death in 1930, at age 56. He was buried in Karori Cemetery in Wellington, with no grave marker. His reputation grew after his death, and a grave marker was added in 1959. And in 2004, a public subscription paid for the addition of a bronze statue of Mrs. Chippy, which now watches over the grave of McNish (fifth image). I would guess that every ship's carpenter who gets anywhere near Wellington drops by to pay his respects to the man who is now the quasi-patron saint of ship’s carpenters everywhere.

The only photo that survives of McNish seems to be a group photo of the crew of the Endurance that was taken early in 1915 (second image). Some brief bios, like the one on Wikipedia, use a fuzzy crop from this photo, but we prefer to leave it intact. McNish is in the second row from the top, at the far left, wearing what looks like a yachting cap. For more about the Endurance expedition, see our posts on Ernest Shackleton and Frank Hurley.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.