Scientist of the Day - Harry Hess

Henry Hammond Hess, an American geologist, was born May 24, 1906. He received a degree in geology from Yale and ended up teaching at Princeton, where he spent his entire career. In 1934, he joined Felix Vening Meinesz on an expedition on a U.S. submarine in the Caribbean, looking for gravitational anomalies, or places where the Earth seems out of balance. Vening Meinesz had made a hundred of these submarine explorations throughout the Atlantic and Pacific since 1926, and essentially discovered the deep oceanic trenches that surround the Pacific, where there are negative anomalies, indicating that the trenches are dynamic, moving down. Hess seems to have emerged from his submarine experience with Vening Meinesz with a strong interest in the dynamics of the ocean floor.

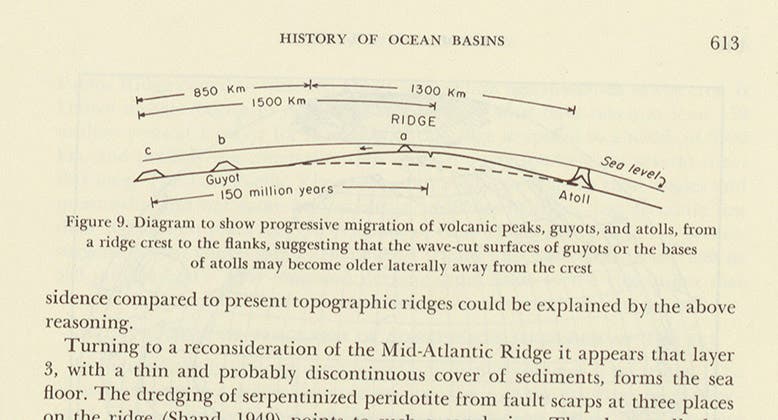

During World War II, Hess commanded a transport ship in the Pacific, participating in the landings at Guam and Iwo Jima, and his ship was equipped with a new invention – sonar. He kept the sonar on all the time, recording the readings, effectively using his trans-oceanic voyages to map the ocean floor. He discovered submarine mountain ranges, and a new kind of geological formation – flattened underwater seamounts, that he named "guyots". He proposed that these were once volcanos that had been flattened by wave action and had gradually subsided, by a mechanism yet to be discovered.

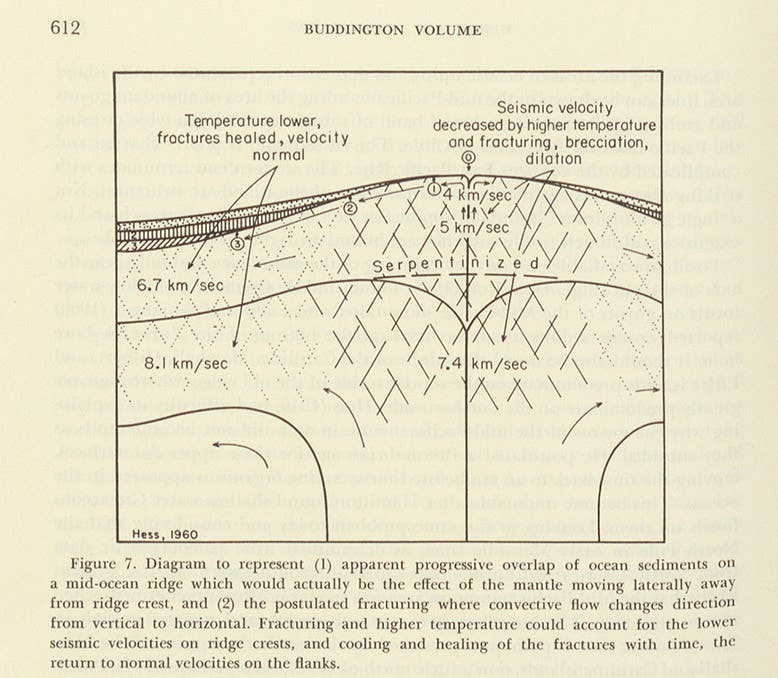

Hess studied soundings of the ocean floor throughout the 1950s, and he was aware of the work of Marie Tharp, at the Lamont Geophysical Observatory at Columbia in New York. Tharp was mapping the results of oceanic soundings and discovered that there is a rift that runs right down the center of the submarine mountain chain known as the mid-Atlantic ridge. Hess knew that the ridge was seismically active, and he also knew that the sediments on either side of the mid-Atlantic-ridge were geologically young. In 1960, he proposed a novel idea.

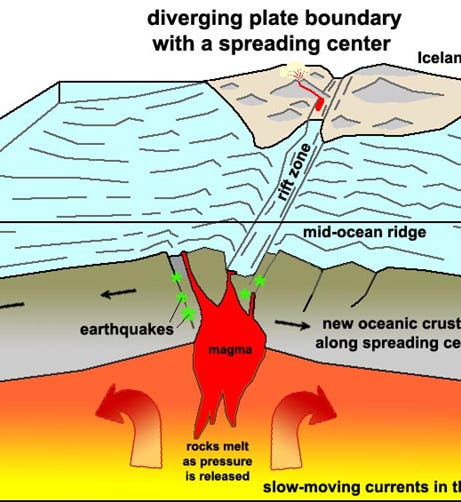

Hess suggested that magma from the Earth's mantle wells up along the mid-Atlantic ridge, forms new rock, and pushes the ocean floor apart. A colleague, Robert Dietz, coined a name for this process – seafloor spreading. Hess proposed that the ocean floor grows as new rock forms along the ridge and moves in both directions, so that the Atlantic Ocean is constantly growing, and Europe and the Americas are slowly but surely moving apart.

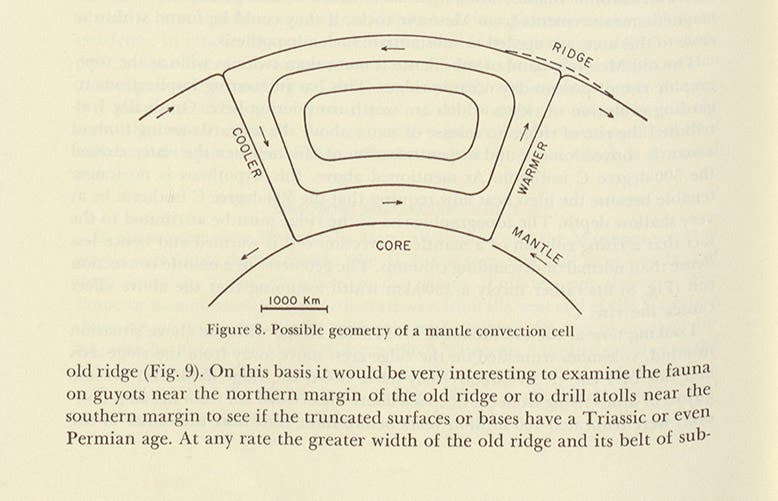

The meteorologist Alfred Wegener had proposed the idea of continental drift back in 1915, but he envisioned that the continents plow through the ocean floor, driven by some unknown force. Hess, like most geologists in the 1950s, would have nothing to do with continental drift. But seafloor spreading was something different. In this scenario, the continents moved apart because the ocean floor between them was growing, and the mechanism here was not mysterious. Convection currrents in the mantle, it was proposed, would bring magma up to the surface, make new ocean floor, and then the currents would drive the two halves of the ocean floor in opposite directions. Hess did not yet understand the function of the trenches – that they were where the old seafloor was subducted back down into the mantle – and the idea that the Earth's surface consists of discrete and separate plates was a concept not yet formulated in 1960. But the notion of subduction zones and tectonic plates would develop quite rapidly, once geophysicists were convinced of the reality of seafloor spreading, as they soon were.

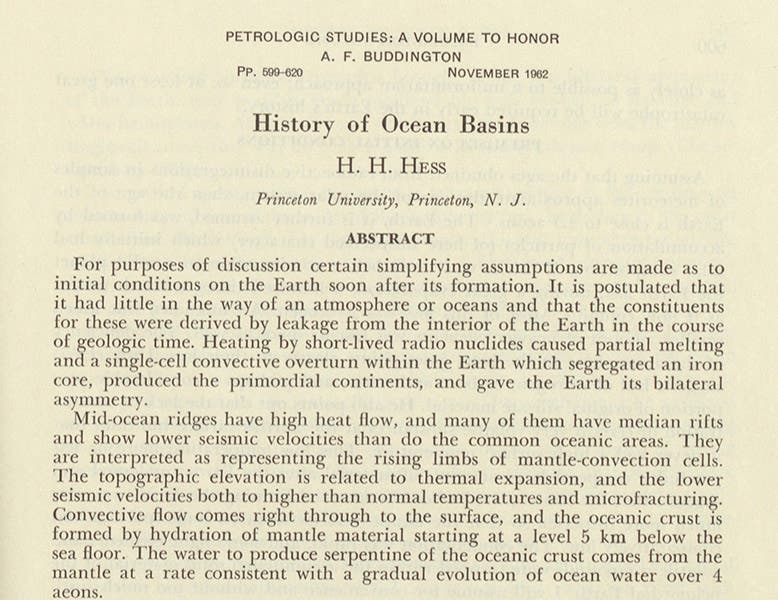

Hess announced his discovery in 1960, and he published the results in 1962 in his contribution to a festschrift for a former professor, Arthur Buddington, a chapter he titled “History of Ocean Basins.” Articles in festschrifts are typically trivial and seldom read, but Hess’s paper made the book a best seller. Most of our images today are diagrams from this seminal article. One shows a cross-section of an oceanic ridge, with newly formed oceanic floor on either side (fourth image, above); another proposes a possible pattern for convection currents in the mantle (fifth image, just above), and a third shows volcanoes, atolls, and guyots as they move away from a ridge and subside (sixth image, below). Our initial image is a modern textbook diagram of seafloor spreading, included to add some color, but also to show the persistence of Hess’s proposal.

The only interesting portrait of Hess is a photo taken during his World War II days, but the only available version is small. We use it anyway, because in all the other photographs, he looks like, well, a mild-mannered university professor, and not at all like someone who set off a revolution in the earth sciences.

This post is greatly indebted to the third volume of The Continental Drift Controversy (2012), written by my good friend and sorely missed colleague, Hank Frankel. If you would like to continue the story of Harry Hess and seafloor spreading, you might want to read his post on the man who first proposed transform faults and tectonic plates, Tuzo Wilson, a post that Hank wrote shortly before his sudden death.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.