Scientist of the Day - Hans Staden

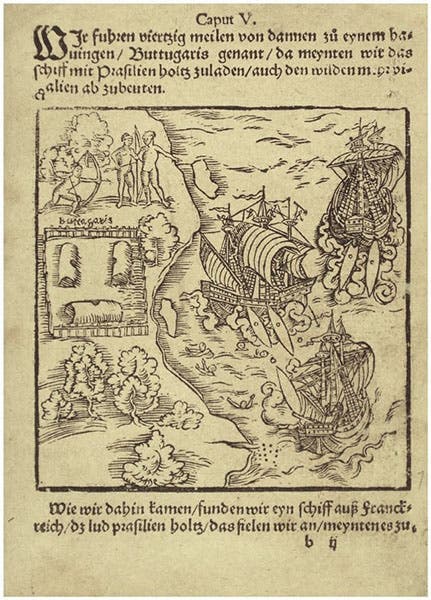

Hans Staden, a German mercenary soldier, was born around 1525, in Homberg (Efze), a town in northern Hesse in central Germany. Like all Hessian mercenaries, he sold his services to whoever would pay, and in Staden's case, he found employment on Portuguese ships ferrying settlers to what would one day be Brazil. He made two trips to the New World, the first in 1548, which was relatively uneventful, and then again in 1550, on a voyage that was much more memorable. The fleet of three ships were all sunk in a storm off the coast of South America; Staden and several others made it to shore and survived in the jungle for two years, before finally making it to Sao Vicente, where he was hired to protect the Portuguese settlement there.

In late 1553, Staden was captured by a band of Tupinamba natives, who were notorious as fierce warriors who ceremoniously ate their captives. Staden was taken to the settlement at Ubatuba, south of Rio de Janeiro, and he managed somehow to avoid a dinner invitation from his captors. He was apparently an observant prisoner, as his later book attested, and he was also clever enough to escape, after about 9 months in captivity. He made it back to France on a French trading vessel, arriving on Feb. 22, 1555, which is about the only calendar date we have for Staden’s life, and the reason we are writing about him on this date.

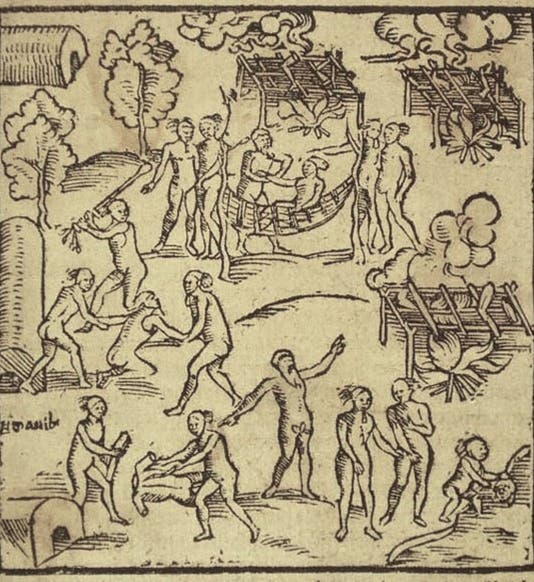

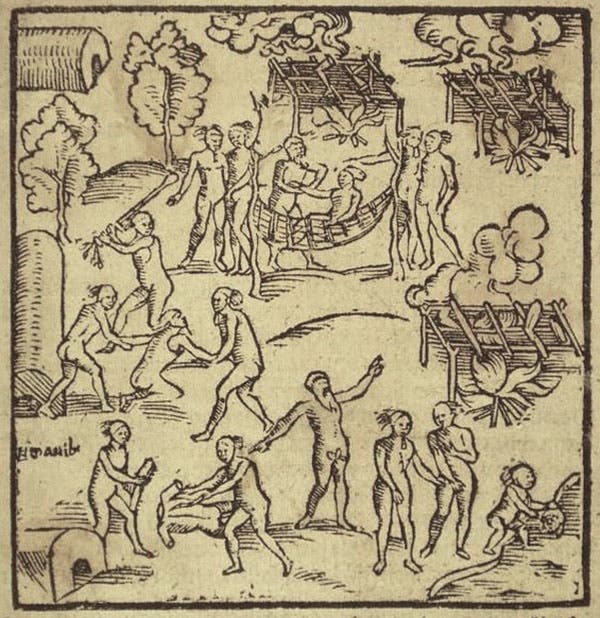

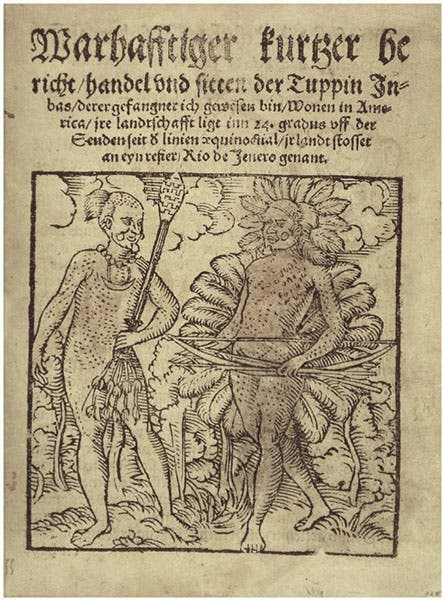

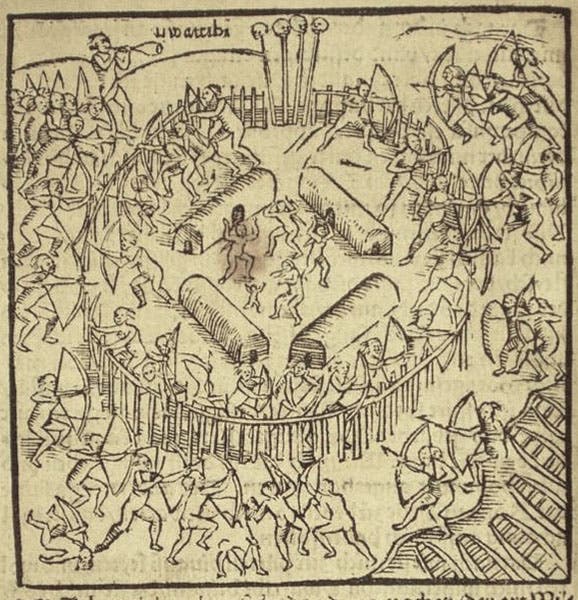

Staden journeyed back to Hesse and took up residence in Wolfhagen. He wanted to write a book about his adventures, but he was not the literary type, or at least he wasn't until he was befriended by Johann Dryander, a physician in Marburg, about 60 miles south of Wolfhagen. We don't know who contributed what, but by 1557, Staden had published a book called Warhaftige Historia und Beschreibung, or in English (and more fully), A True History and Description of a Land of wild, naked, grim, man-eating People located in the New World of America. The book was illustrated with about 55 woodcuts, by my count, very crude, but most nearly full-page, many depicting the social and cultural activities of the Tupinamba. We do not have a copy of Staden’s Warhaftige at our library , so we illustrate this post with images from a copy at the Biblioteca Nacional do Rio de Janeiro, available online at archive.org.

The book was an immediate best seller. There are never been anything like it, for unlike most such books up to that time, the descriptions rang true – it was apparent that Staden had really undergone some amazing experiences. The second part of the book is all about the Tupinamba, and describes how they lived, what they ate and how they prepared it, and, of course, what they did with their captives, which is described in great detail. I did not realize, until I read Staden, that sometimes a woman of the tribe would have sexual congress with a male captive, and if a child resulted, he or she would be raised to adolescence, and then killed and eaten. That is slow revenge, and lends new meaning to the expression, nursing a grudge.

Staden’s book barely beat André Thevet’s Singularities of the French Antarctica (1557) into print, which also had woodcuts of cannibals, but which were copied from Staden, since Thevet never saw any. Staden’s book was reprinted many times and was eventually included in Theodor de Bry’s Grand Voyages series, as America Part III (1593), for which the original crude woodcuts were turned into elegant engravings by Theodor’s son, Johann Theodor de Bry. Staden’s descriptions of the Tupinamba culture have borne up well over time; he really is the father of New World cultural anthropology. His accounts of cannibalism were so disturbing that John White, when he illustrated Thomas Harriot’s A Briefe and True Report of the new found Land of Virginia (1590) for Theodor de Bry, went out of his way to depict the Algonquin natives engaged in peaceful activities, such as dancing, building canoes, and fishing. You can see some of White’s watercolors at our post on White.

Nothing is known about Staden’s life after 1558, although it is assumed he died around 1576. They are apparently prouder of Staden in Wolfhagen than in his hometown of Homberg, for Homberg honors Staden with a wall-plaque (second image), but Wolfhagen has a life-sized bronze statue situated on a city square (sixth image). Staden holds up a copy of his book for all to see (but not read – it is a bronze book), and he is dressed in the slashed pantaloons and blouse of a Landsknecht, although he was really an arquebusier, or rifleman. I guess the challenge of rendering all that ribboned cloth in bronze was too much for the artist to resist.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.