Scientist of the Day - Hans Sloane

Hans Sloane, an English naturalist, physician, and collector, died Jan. 11, 1753, at the age of 92. He had been born Apr. 16, 1660, to Scottish parents transplanted to Ulster in northern Ireland. When his father died when he was young, Hans and his brothers were taken in by a patron who saw to their education. From an early age, Sloane was a collector of natural objects, especially plants. He came to London as a young man, where he met John Ray, the celebrated naturalist, then working on his Historia plantarum. Sloane traveled to France and continued to collect, not only plants, but a medical degree from Orange. When he returned to London, he proceeded to establish himself in scientific society, and in 1685, he was elected to Fellowship in the Royal Society, which was born the same year Sloane was.

When Christopher Monck, the Duke of Albemarle, was appointed Governor of Jamaica in 1687, he asked Sloane (then 27) to come along as family physician, which Sloane was happy to do. It is not clear whether he got to cross the Atlantic on the Duke's yacht, or on the accompanying naval vessel – one would think the former, as the Duke might well want the family physician near at hand. They stopped at Barbados on the way, and Sloane was able on later occasions to visit several other Caribbean islands, and he collected everywhere – mostly plants, but also insects and fish, and ethnographic objects. It is probably a good thing that the Duke died 15 months into his governorship, and his wife decided to return home, bringing Sloane with her, or else the collecting might have gotten out of hand.

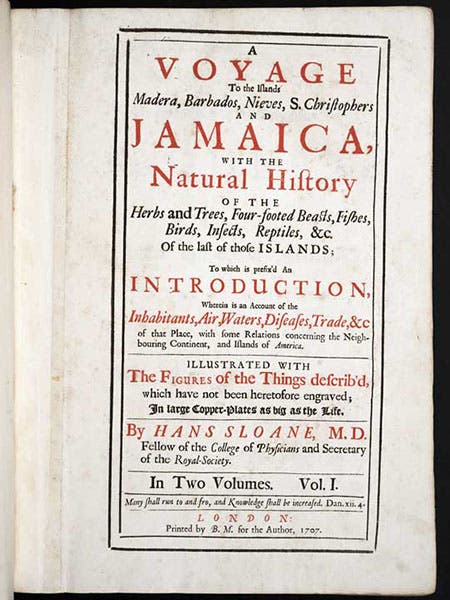

As it was, it took Sloane almost 20 years to publish the first volume of his narrative (the plant volume), and another 18 years to produce the second volume. The work was titled A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, S. Christophers and Jamaica, with the Natural History of the herbs and trees, four-footed beasts, fishes, birds, insects, reptiles, &c. of the last of those islands (1707-25), although is it nearly always called Sloane's Natural History of Jamaica. We have a lovely set in our collections (third image).

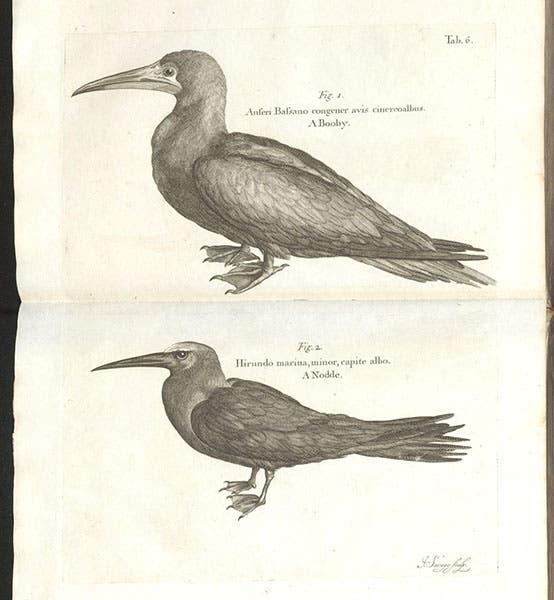

Both volumes are large and a bit unwieldy on the bookstand, although they look splendid on the shelves in their calf bindings. There are a huge number of engravings in each volume (156 in volume 1, most of them at the end), nearly all full page or double-page, which must have cost a fortune to engrave and print, but by that time (1707) Sloane was rich, having married a wealthy widow. The plate showing a Booby and a Nodder is an especially nice one (fourth image). The figures were drawn by either Garret Moore in Jamaica or by Everhardus Kickius in England, and engraved by the inimitable Michael van der Gucht (who had earlier engraved the marvelous plates in the Orang-Outang (1699) of Edward Tyson).

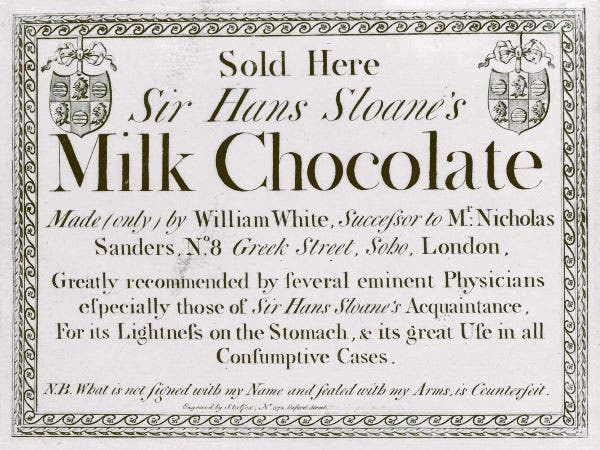

The most reproduced engraving shows the cacao tree (fifth image), the seeds of which are the source of cocoa and chocolate; the engraving is well-known because Sloane is supposed to have discovered and introduced into England the practice of mixing milk with chocolate, to make the chocolate less bitter. The point is often made that Sloane may have done so, but he was hardly the first. Nevertheless, in England, Hans Sloane is identified with milk chocolate, as we can see from a trading card of the 18th century, offering Hans Sloane’s milk chocolate (sixth image).

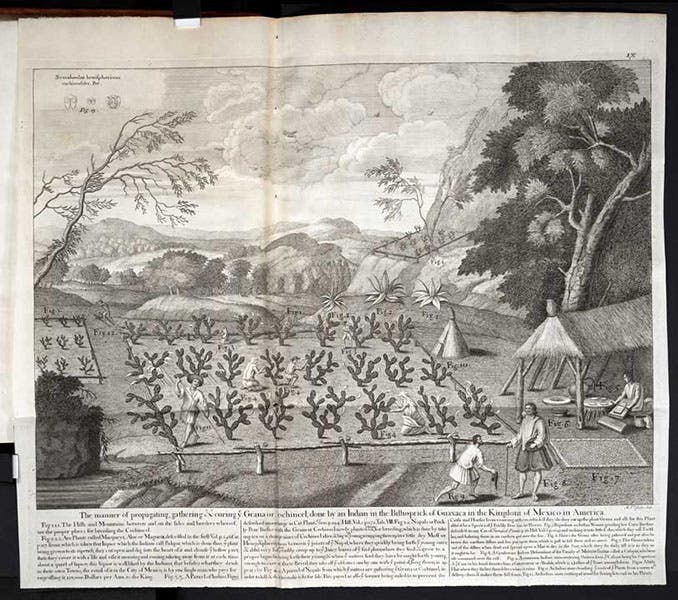

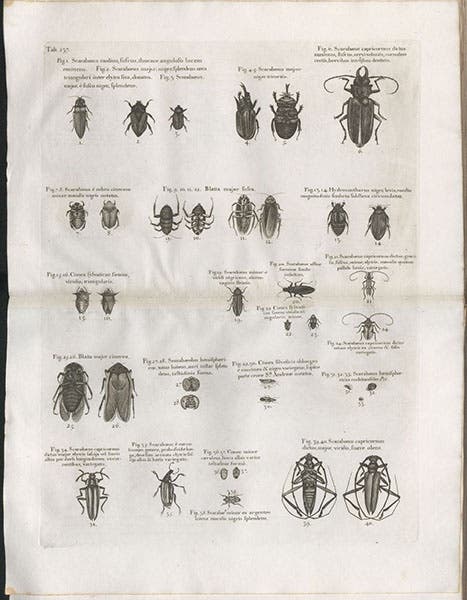

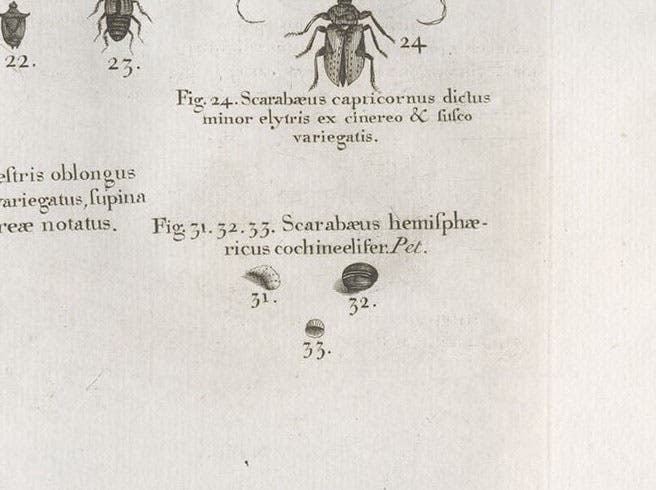

My favorite illustration in A Natural History of Jamaica is near the beginning of volume 2, showing a prickly pear (Opuntia) plantation in Oaxaca, where the principal crop is not nopales, but rather the tiny cochineal scale insects that feed on the leaves and are the source of a unique and intense red dye (seventh image). The engraving depicts natives gathering the bugs from the plants. No insects are pictured there, because at that scale they do not show up, but on another plate (plate 237), showing a variety of insects, there is a set of three figures (31-33) that depict the miniscule cochineal insect. We show you both the full plate and a detail (eighth and ninth images, below).

When Sloane died in 1753, he bequeathed his entire collection of 71,000 items (including a library of 50,000 books) to the British nation, provided the government would pay £20,000 into the estate to support his two daughters. Thie terms were accepted, and 6 years later, the British Museum opened its doors. We will tell this story in a second post, talk about Sloane’s later life and career, and also discuss the Museum’s recent decision to move Sloane’s bust from its pedestal of privilege as Museum founder into a case devoted to slavery and the British empire, in order to bring into the open the fact that Sloane made much of his fortune from slave-holding plantations owned by his wife in the Caribbean.

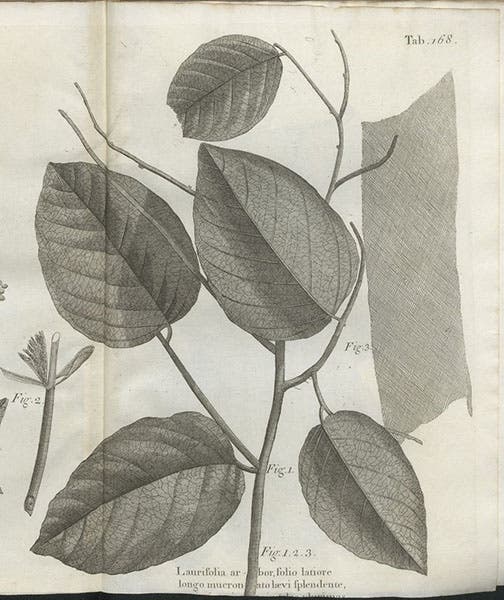

The portrait of Sloane by Stephen Slaughter in the National Portrait Gallery in London is especially nice (second image). It depicts Sloane holding one of the drawings made by Kickius of a Jamaican plant, it this case the lacebark tree, Lagetta lagetto (to use its Linnaean name, introduced after Sloane). Just because I could, I found the engraving in A Natural History of Jamaica, made from that painting, and show it as our last image, just above.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.