Scientist of the Day - Hans Geiger

Hans Geiger, a German physicist, was born Sep. 30, 1882. Geiger earned his PhD in Germany and then came over to Manchester, England, in 1907 to work with Ernest Rutherford, who had recently unraveled many of the mysteries of radioactivity. Rutherford, beginning in 1908, was bombarding materials with alpha particles--emitted by radium--to see what happened. The usual way to detect a particle was to look for scintillations, tiny flashes of light given off when an interaction took place. Geiger invented a crude device that provided an audible "click" when a particle went through a detector. It would be called (much later) a Geiger counter.

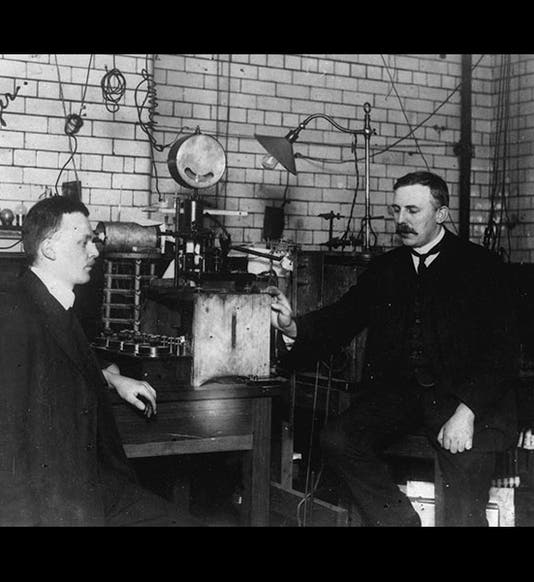

Geiger is best known among physicists, not for his counter, but for an experiment he did with Ernest Marsden in 1909. Under the guidance of Rutherford, Geiger and Marsden bombarded gold foil with alpha particles, and they noticed that, while most of the particles went straight through the foil, occasionally a particle bounced straight back, which was most surprising, since an alpha particle was thought to be a tiny solid bullet and the atom was thought to be a diffuse mass. In 1911, Rutherford used the Geiger-Marsden experiment to argue for the existence of an atomic nucleus, a dense region of positive particles that could indeed reflect back an alpha particle that struck it directly. The first photo above shows Geiger (on the left) and Rutherford in the lab in 1912.

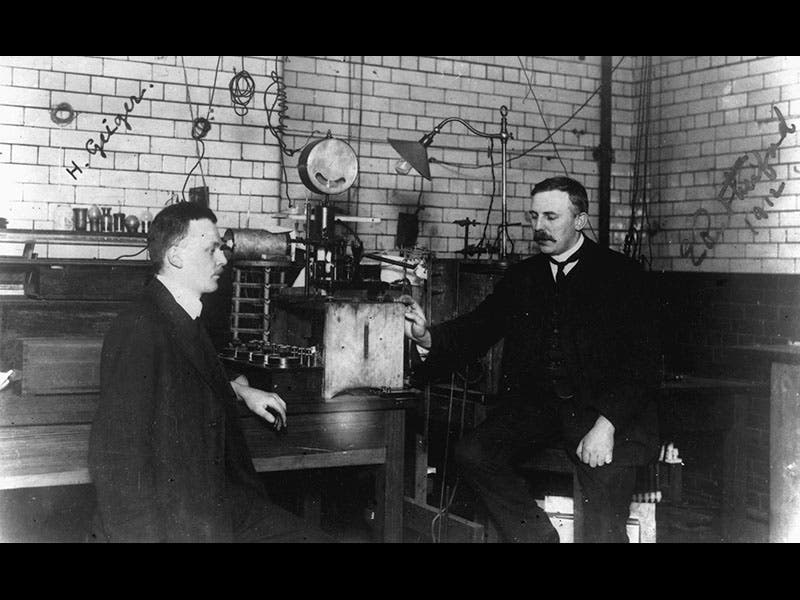

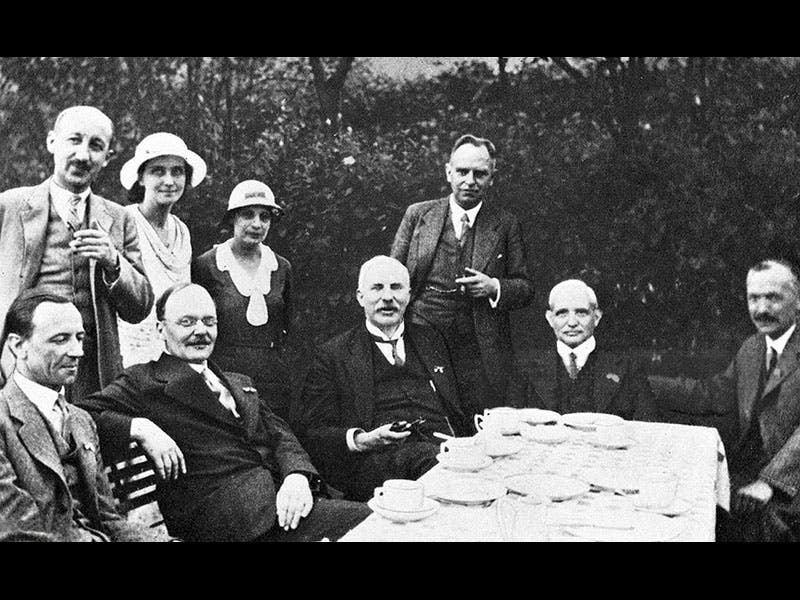

Later, Geiger and Walther Müller turned Geiger’s early crude particle counter into a very useful detection device, and we see above a Geiger-Müller tube of 1932 (second image). Geiger was certainly in good company in a group photograph of the same year (third image), where Geiger (second from left in front) is surrounded by James Chadwick, discoverer of the neutron (extreme left); Rutherford (to Geiger’s right), and Lise Meitner (behind Geiger) and Otto Hahn (behind Rutherford), who would split the atom in 1938. But Geiger’s career and reputation went downhill after 1932, at least outside Germany. He seems to have been caught up in the fervor for a "German science" in the 1930s, and his ties with other Western scientists were gradually severed. Hans Bethe recalled that when he lost his job in Tübingen in 1933, he appealed to Geiger (a professor at Tübingen) for help, and Geiger turned his back on him. It is revealing that when physicist George Gamow wrote his folksy history of early twentieth-century physics, Thirty Years that Shook Physics (1966), he did not so much as mention Geiger anywhere. Somewhere along the line, Geiger lost the respect of his colleagues and disappeared from their accounts of the birth of atomic and nuclear physics.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.