Scientist of the Day - Hans Christian Gram

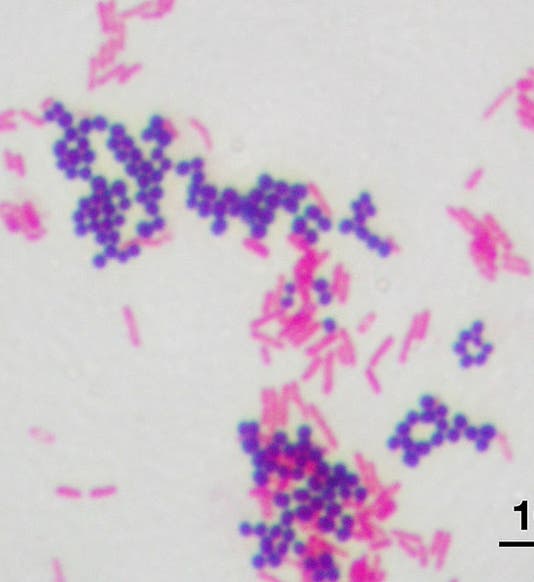

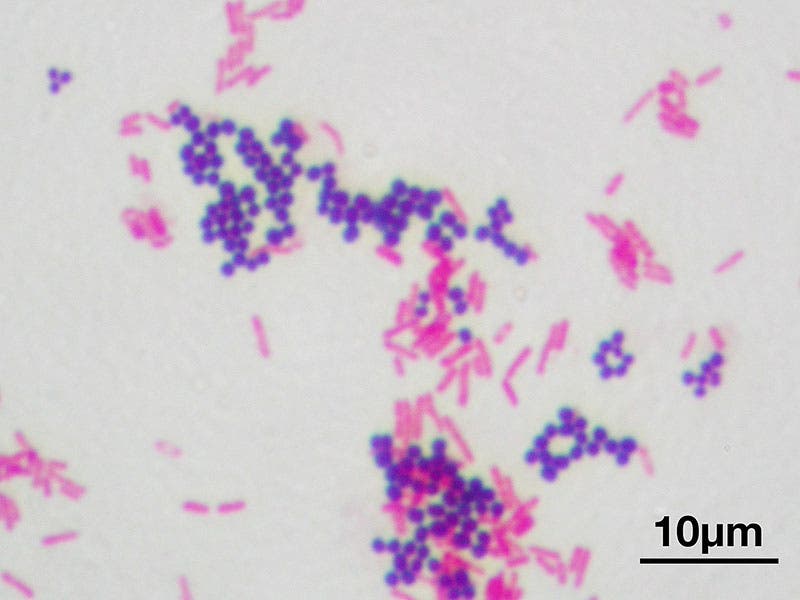

Hans Christian Joachim Gram, a Danish physician and bacteriologist, was born Sep. 13, 1853. Gram received his medical degree from the University of Copenhagen in 1883 and went to work in a medical laboratory in Berlin, where he studied bacteria. Bacteriology was not a new science – Anton van Leeuwenhoek had observed bacteria with his single-lens microscopes in the 1670s – but the notion that bacteria were the cause of many human diseases was a new idea, the outgrowth of the work of Louis Pasteur and others in the 1870s. The problem with studying bacteria under the microscope is that, until the invention of the phase-contrast microscope in the 1930s, bacteria were very hard to see, and so microbiologists were trying out various stains to see if they could make the bacterial cells stand out from the background. Gram was doing just that in 1884, when he found that bacteria could be stained purple by a compound called crystal violet. If you then washed the culture with ethanol, many bacteria lost the purple color. And if you then counter-stained them with a compound called safranin, those bacteria took on a rosy pink color.

Gram was just looking for a way to see bacteria in his microscope. But it turned out that bacteria that took the purple stain – soon called gram-positive bacteria – were majorly different from those that rejected the stain – called gram-negative. Staphylococcus, discovered in 1880, was gram-positive, while Escherichia (as in E. coli), is gram-negative. So it was possible, with a very simple test, to eliminate about half the pool of candidates for the bacteria you were trying to identify. Gram staining came into widespread use very quickly in bacteriological labs.

But the amazing thing about Gram staining is that it is still in common use in hospital laboratories today. When a patient comes in with an infection, cultures are taken and Gram-stained immediately, to weed out the pathogens that cannot be the cause of the infection. If the culture is gram-negative, then Staph aureus is not the culprit. My daughter, who is an intensive-care pediatric physician at a children’s hospital, told me that they once admitted an extremely sick child who had gram-negative cocci in her blood. Since there are not many cocci that are gram-negative, they suspected meningococcemia, a dangerous blood infection, and were able to administer the appropriate treatment to her before her condition worsened, which it certainly would have. and the proper antibiotics to her family. Hans Gram had saved the day!

I know little about modern medical practice, but I would be surprised if there are many medical techniques from the 19th century that are still in common use. Antisepsis is the only practice I can think of, and I am sure modern antisepsis is quite different from that of Ignaz Semmelweiss and his contemporaries. If I am wrong – which is very possible – I hope someone will enlighten me.

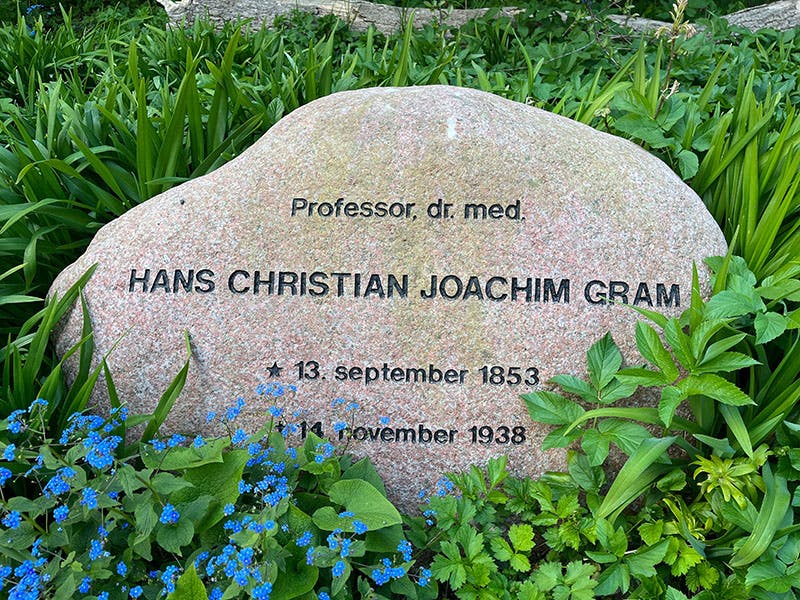

Gram became well known for his discovery, probably because someone early on attached his name to the staining procedure, and since he developed his technique just a year out of med school – he was 31 years old at the time – he had half a half-century to enjoy his fame. I hope he did. When he died on Nov. 12, 1938, he was laid to rest in Copenhagen's Assistens Kirkegård, where his simple headstone (fourth image) shares hallowed ground with Hans Christian Andersen, Søren Kierkegaard, Hans Christian Oersted, and Niels Bohr.

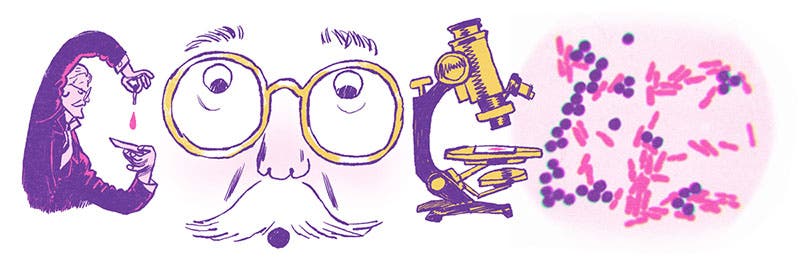

Four years ago, on this day, Google ran a Google Doodle honoring Hans Gram and his staining technique, which you can see in our last image. The doodle ran in Great Britain, Germany, Iceland, Scandinavia, Italy, Greece, Ukraine, Australia, New Zealand, India, Argentina, Peru, and Canada, but not in the United States, Russia, China, or any country in Africa. I am sure someone high-up in Google echelons can explain that distribution.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.