Scientist of the Day - H.G. Wells

Herbert George Wells, universally known as H.G. Wells, was born Sep. 21, 1866, in Kent, England. Wells was and is renowned as a science fiction writer, a socialist reformer, and a futurist. It is his science fiction, his early science fiction, that will attract our attention today. If Jules Verne invented science fiction as we know it, Wells gave it a new dimension, as we will explain. His first science fiction novel was The Time Machine (1895), which introduced the idea of time travel and coined the term "time machine". The Invisible Man followed in 1897, The War of the Worlds in 1898, and The First Men in the Moon in 1901. The plot of each of these was driven by a new and perhaps implausible invention, but one that is then treated rationally and scientifically, so that the story that develops seems quite plausible. Since we cannot deal with all of them in one post, we will focus today on The First Men in the Moon, which I have read most recently, and of which I am quite fond, for reasons I am not sure I can explicate, but I will try.

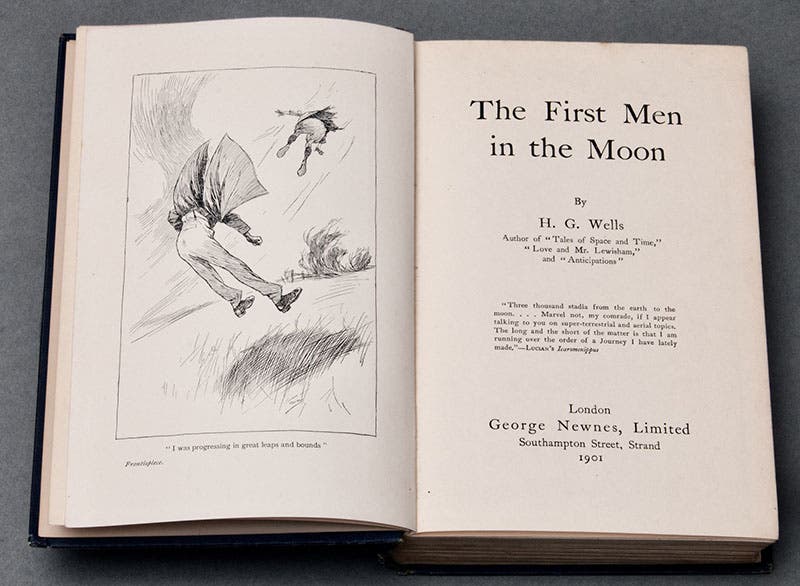

The story is built around an invention, cavorite, a material that, as the inventor, Mr. Cavor puts it, is "opaque to gravity.” This means that if you have a sheet of cavorite, everything above it will feel no gravitational attraction and will shoot upward. It also has the interesting property of being transparent to gravity waves when it is above 60° F, becoming opaque only when its temperature drops to sixty. Its first successful manufacture is signaled when Cavor is visiting his neighbor (and the narrator), Mr. Bedford, and the temperature of Cavor’s cottage laboratory drops to the crucial level, so all the air in the cottage above the sheet flies upward, taking the roof and much else with it. As air rushes in to replace that which has become weightless, the wind lifts poor Cavor and Bedford off the ground, as the frontispiece of the book depicts (fourth image).

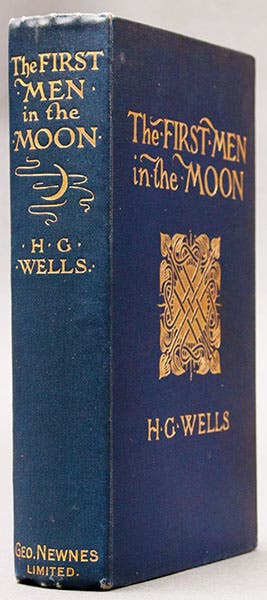

Bedford, who is broke, wants to make money from the invention; Cavor wants to go to the Moon. Cavor not only prevails, he convinces Bedford to go along. Cavor builds an octagonally-shaped spherical spacecraft, made of steel with moveable cavorite panels on the outside (first image). Slide one of the panels to the side and the sphere rushes off in that direction. Remove the top panel, and one can fly to the Moon.

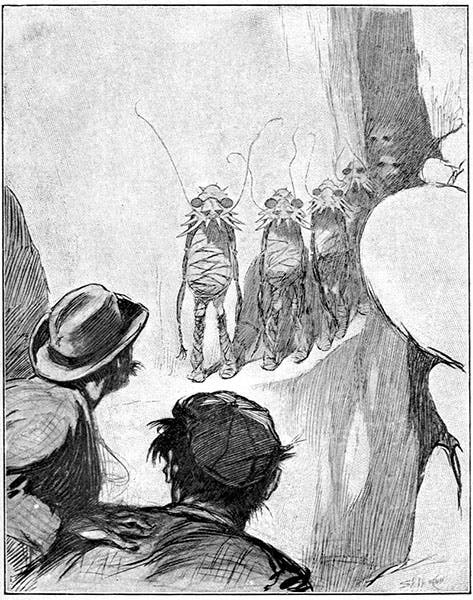

The two do make it to the Moon, and I won't reveal too much more, except to say that they do encounter life there, not only plant life, but two forms of animal life: moon-calves, and Selenites, who feed on the moon cattle. We see the Selenites, which Cavor likens to insects, in one of the other illustrations that decorate the first edition of the book (fifth image). Cavor will be captured by the Selenites and taken to their subsurface lunar realm, while Bedford is able to return to Earth, an essential plot element, if the story is to be told.

Several Wells scholars have pointed out The First Men in the Moon is typical of Wells' approach to fiction; inventing a device of some sort which might be implausible, and then following all the scientific rules in the story that ensues, so that what was implausible is gradually shaped into plausibility. This is what happens with cavorite, and the time machine, and the altered refractive index of the human body that makes the Invisible Man invisible. It is the realism of the rest of the story that keeps the fantastic elements in line.

I do admit that my fondness for the novel might derive from my fondness for the film, First Men in the Moon, that came to the screen in 1964. Actually, it is not a very good film, because it is scientific farce rather than fiction, but I do so love Lionel Jeffries in the role of Mr. Cavor. He is the perfect bumbling, successful-in-spite-of-himself, inventor, and about as far removed from the super-competent Captain Nemo as one could get.

On some future occasion we should write about The Time Machine (also made into a film, but a much better one), and perhaps discuss Wells’ role as futurist (he seems to have understood the possibilities of atomic energy, and atomic weapons, long before the rest of us). He was also a successful world historian in his later years; we might look at the role played by science in those surveys.

There are lots of photographs of Wells, but I like the statue sculpted by Wesley Harland for the town of Woking, where Welles lived while writing most of the science fiction novels we just mentioned (second image). He appears to be holding a cavorite spacecraft in his hand.

Finally, we should mention that the Linda Hall Library does not own any of Wells’ science fiction novels, nor any of those of Jules Verne, or any of the other pioneers in the genre. That follows a collections policy decision made long ago. I for one would like to see us collect some early science fiction, like 20,000 Leagues under the Sea and The Time Machine, since they are so important for helping us understand the scientific culture of the time.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.