Scientist of the Day - Guillaume Amontons

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

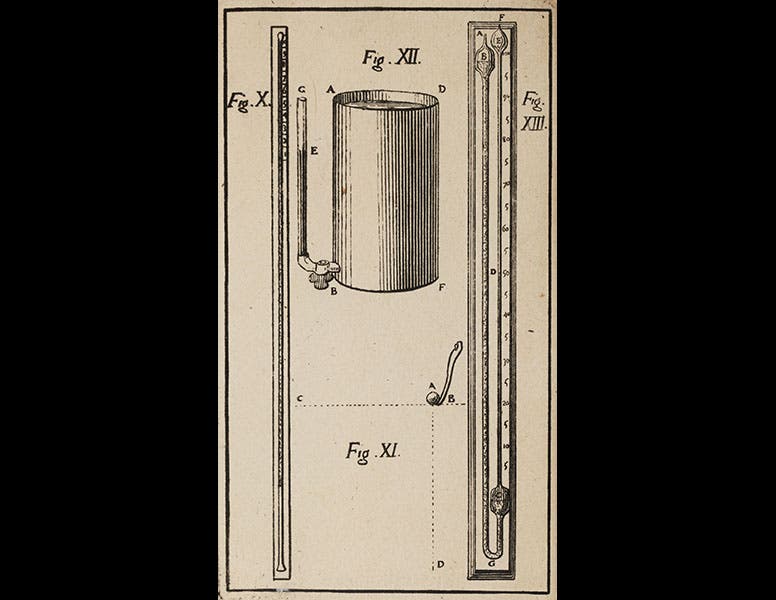

Guillaume Amontons, a French scientific instrument maker and inventor, was born Aug. 31, 1663. The barometer was about 40 years old when Amontons began suggesting improvements. One of his barometers had a tapered section at the top that supposedly allowed more precise readings. Another was a double barometer, which allowed the instrument to be half as tall as conventional instruments. He also invented a thermometer that was based on a barometer's sensitivity to changes in temperatures (third image, Fig XIII).

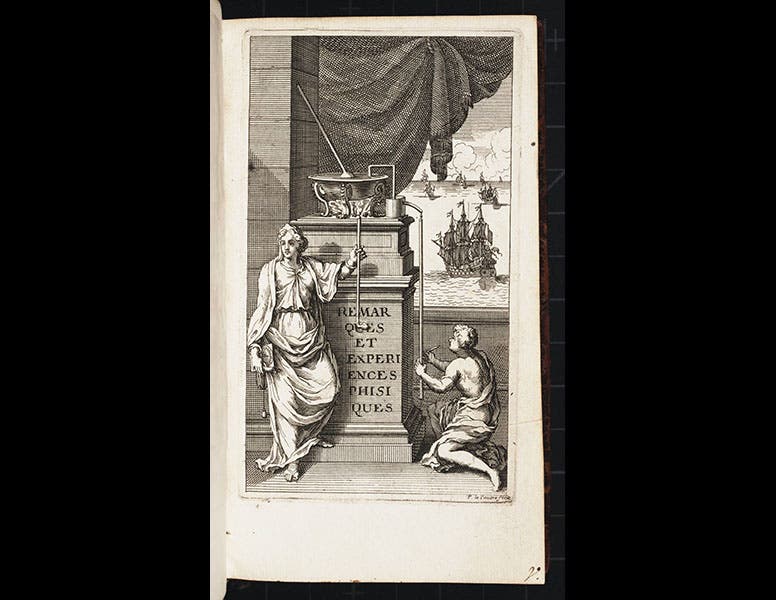

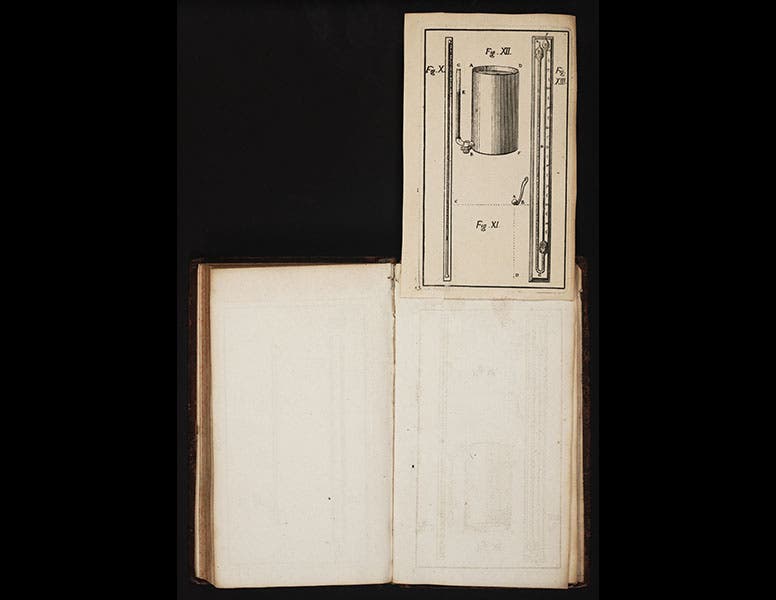

Amontons published a number of papers in the Journal des Sçavans, but only one book: Remarques et experiences phisiques sur la construction d'une nouvelle clepsidre, sur les barometres, termometres, & higrometres (Remarks and physical experiments on the construction of a new water clock, and on barometers, thermometers, and hygrometers, 1695, second image). We have this book in our History of Science Collection; it has a handsome frontispiece that shows his new clepsydra, which supposedly would work on a ship at sea (first image), but most of the book, and all of the plates at the end, depict and discuss a variety of barometers and thermometers, including the three we mentioned briefly at the outset. The most remarkable feature of our copy of the book is the way the plates are mounted: they are glued face-down and upside-down to stubs at the top, rather than at the left, so that the plates unfold upward (fourth image).

One of Amontons’ principal goals in life seems to have been membership in the Paris Academie des Sciences, and this he finally achieved, so his last papers appeared in the Histoire et Memoires of the Academy. But there weren’t many, because he died in 1705, at the age of 42.

Sometime in the 1680s, Amontons seems to have made an attempt to find patronage for an optical telegraph. I haven't found that paper yet, if he did describe it in a paper, but 180 years later, Louis Figuier gave Amontons credit for first proposing an optical telegraph, and he even included a wood engraving of Amontons and his optical instruments in his Merveilles des sciences (1868; fifth image). Of course, perhaps Figuier--a Frenchman--just preferred to give credit to another Frenchman, rather than to that English scoundrel Robert Hooke.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.